![]()

PART I

THE NORMAN CONNECTIONS CASTLES

![]()

1

NORWICH CASTLE

Elizabeth Popescu

Résumé

Cet article approfondira l’interprétation archéologique du château de Norwich et de ses remparts, un joyau de son époque. Son donjon normand impressionnant a été décrit comme étant, sur le plan architectural, une des constructions les plus ambitieuses de son temps en Europe occidentale. Il a été parmi les 40 premiers châteaux urbains à être construits avant 1100, et sa surface s’étend sur une grande partie du territoire de Norwich qui est devenue l’une des villes majeures d’Angleterre en 1066. Pendant presque un siècle, Norwich a été l’unique château royal dans le Norfolk et le Suffolk et a exercé les fonctions de centre administratif dans une région extrêmement riche. Une importante clôture de terres relevant directement de la couronne – les “droits” ou “libertés” (Fee ou Liberty) du château – était délimitée dans la proximité immédiate du château et la juridiction royale a été maintenue dans cette enceinte jusqu’en 1345. Deux grands murs d’enceinte furent érigés au sud et au nord-est de cet enclos, devenue plus tard la rue de Castle Meadow. Une barbacane fut ajoutée au XIIIe siècle. Au milieu du XIIIe siècle, le château de Norwich se trouvait au cœur d’une ville fortifiée plus vaste que Londres, son développement étant influencé par le cours caractéristique de la rivière Wensum.

Dans le cadre de la construction d’un centre commercial souterrain, des travaux d’excavation importants ont été menés sur le site du château entre 1987 et 1991 par l’unité d’archéologie du Norfolk: à l’époque, il s’agissait du plus grand projet de ce type en Europe du Nord. Cet essai prend en compte les résultats des fouilles en relation avec l’impact du château sur la topographie de la ville actuelle, et retrace le développement du donjon et de ses remparts dans leurs phases de bois et de pierre, avec une attention particulière portée sur les périodes de construction les plus importantes entre environ 1067–70 et 1122. On inclut un bref résumé de la manière dont le château et son enclos (Fee) ont continué d’influencer le développement du cœur historique de Norwich jusqu’à notre époque.

Introduction

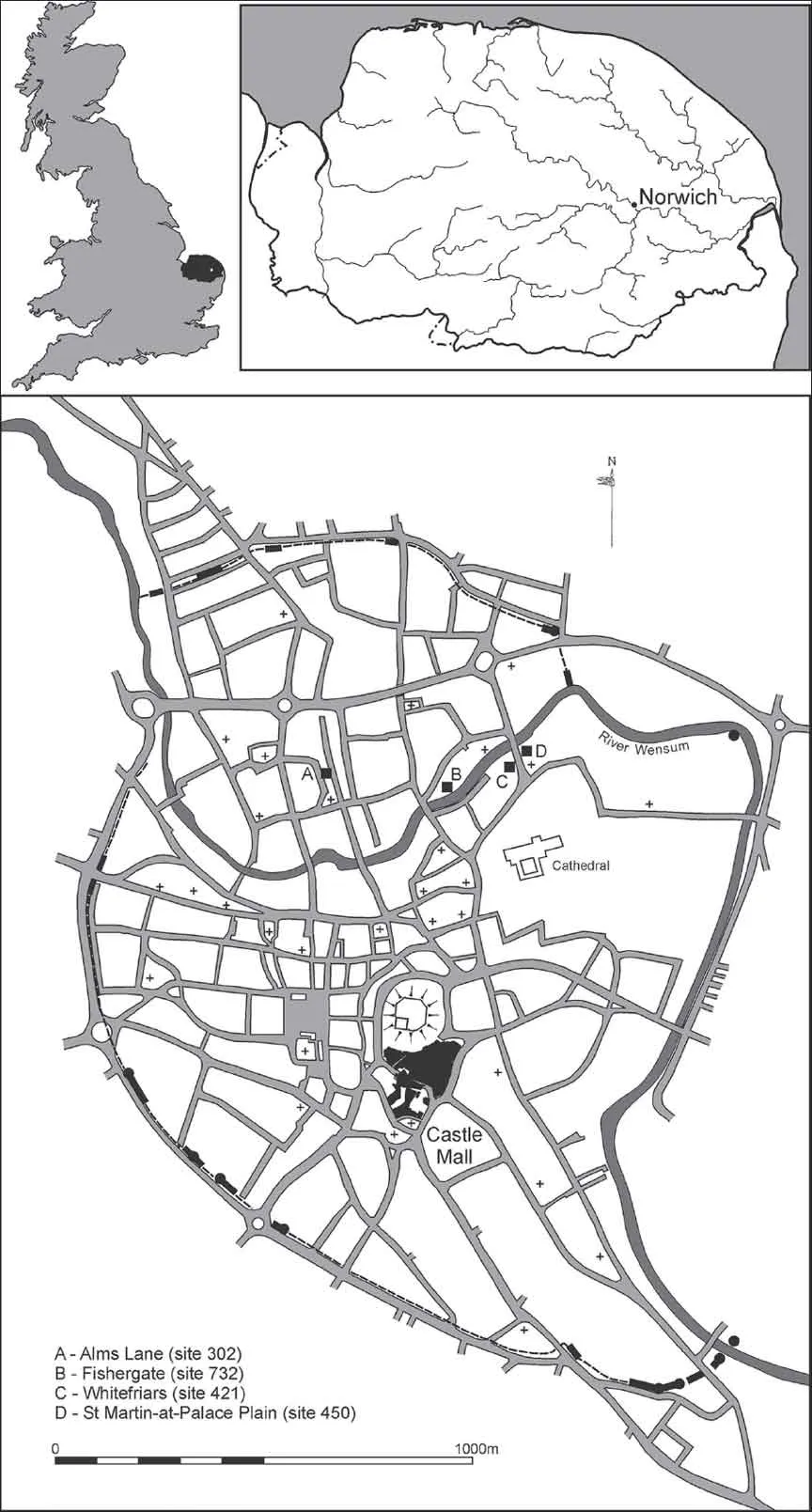

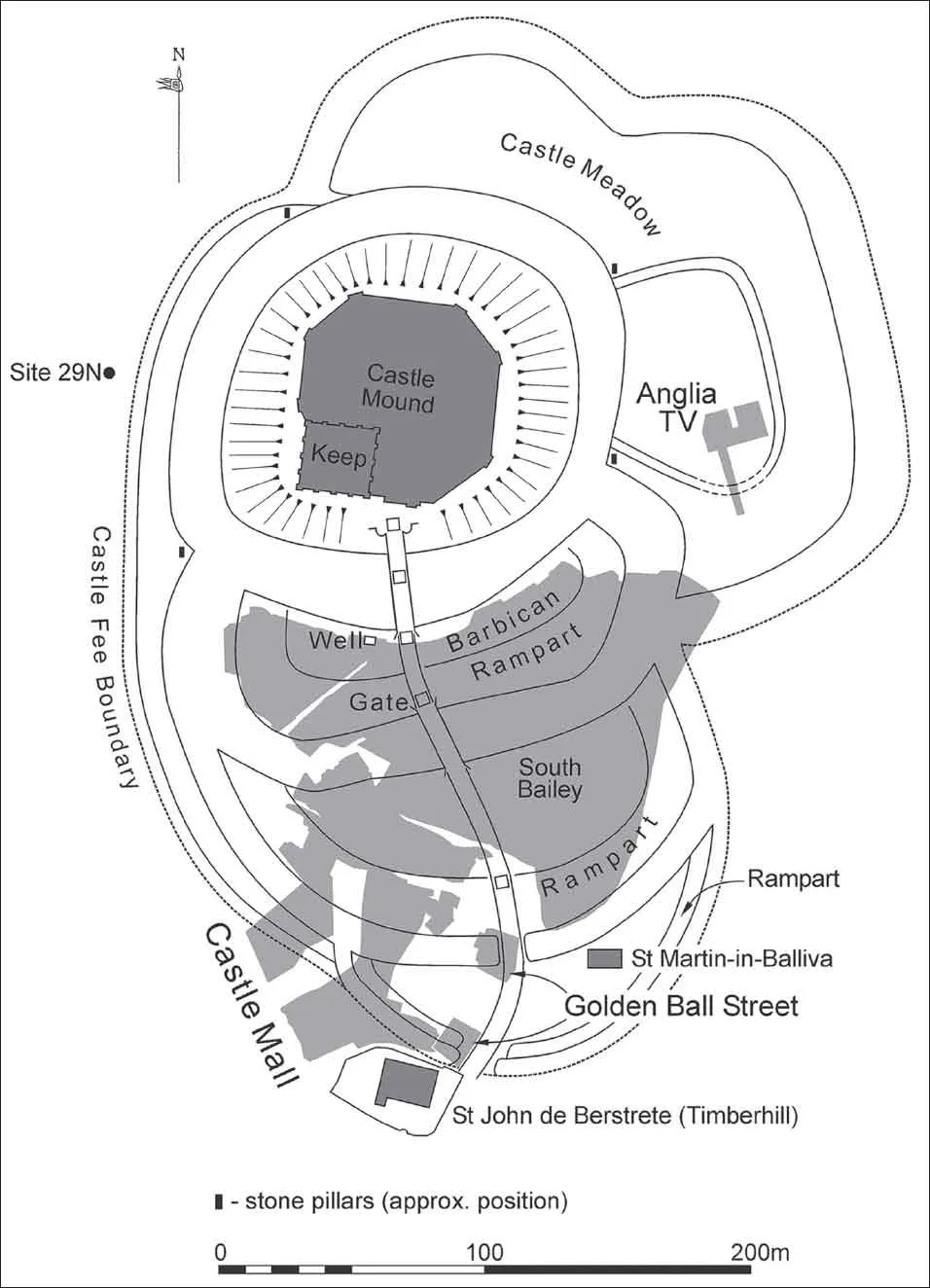

Norwich Castle was one of the finest Norman fortifications in England. Its great Norman keep or donjon has been described as ‘architecturally the most ambitious secular building [of its time] in western Europe’ (Heslop 1994, p. 66). It was one of more than 40 urban castles established before 1100, and overlies a substantial part of what had become one of the dominant towns in England by 1066. By the mid-14th century, it lay at the heart of a walled city larger than London, the distinctive shape of which was influenced by the course of the River Wensum (Figure 1.1). Norwich was to remain the only royal castle in Norfolk and Suffolk for nearly a century, serving as the administrative centre of an extremely wealthy area. A substantial precinct of Crown land (Feodum Castelli: Fee or Liberty of the castle) was defined immediately around it and royal jurisdiction was maintained over the enclosure until 1345. Within the Fee, two large baileys were laid out to the south and north-east, the latter being known as the Castle Meadow (Figure 1.2). A barbican complex was added in the 13th century. At its largest extent, the entire castle precinct encompassed about 9.3 hectares (23 acres).

Recognition of the site’s national importance led to its scheduling in 1915 (SAM Norfolk 5), the protected area being extended in 1983 to enclose much of the Fee. Despite eventual landscaping for a Cattle Market most of the south bailey remained open space. Redevelopment for a retail centre – named Castle Mall – led to a major excavation by the Norfolk Archaeological Unit between 1987 and 1991 (covering 2.3 hectares, 5.7 acres; Site 777N): at the time of excavation, this was the largest project of its kind in northern Europe. Further excavations took place at Golden Ball Street in 1998. The results from both sites are published in two monographs (Parts I and II; Shepherd Popescu 2009a and b), supplemented by occasional papers on zooarchaeology (Part III: Albarella et al. 2009) and additional documentary evidence relating to the 71 medieval properties that lay within the Castle Fee (Part IV; Tillyard et al. 2009). The project also has a digital aspect, which provides full details of the various cemeteries at the site (Part V; Shepherd Popescu 2009c). An additional report on supplementary excavations at the castle mound in 1999–2001 is in preparation (Wallis, forthcoming).

Figure 1.1. Location of Norwich and of the Castle Mall and Golden Ball Street sites (Norfolk Museums Service).

Figure 1.2. Plan of excavated areas at Castle Mall and Golden Ball Street, showing modern street names and the footprint of the excavations against the castle defences (Norfolk Museums Service).

Natural topography

Contrary to popular opinion Norfolk, and more particularly Norwich, are not flat. The city is dominated by two areas of high ground: Mousehold Heath to the north-east and the Ber Street ridge to the south. The site selected for the castle had a naturally dominant position, lying at the northern end of the Ber Street ridge: one obvious suggestion for the origin of the street name refers to the limit of the Saxon burh (Armitage 1912, p. 174), although another suggestion is that it derives from the Old English (WSax) beorg or Angle berg meaning ‘hill’ or ‘mound’ (Hudson 1896, p. 17; Sandred and Lindström 1989, p. 88). To the west of the castle site a stream – the Great Cockey – ran northwards to the Wensum in its own valley. This watercourse later separated the castle precinct from the Norman market place to the west, at the same time defining much of the eastern edge of the Jewish Quarter.

The pre-Conquest landscape

Middle Saxon Needham?

Norwich Castle has long been believed to overlie part of the pre-Conquest settlement of Needham, one of five hamlets or villages founded in the 8th to 9th century that had, by the 11th century, coalesced to form the town of Norwich. The place-name implies a poor homestead or meadow (Sandred and Lindström 1989, pp. 140–1). Although the initial findings of the excavation did not appear to indicate direct activity in the area during the Middle Saxon period, burials in a cemetery beneath the barbican rampart were later radiocarbon dated to the 8th to 9th centuries. Needham may have consisted of little more than a collection of farmsteads (Green and Young 1981, p. 10) and the presence of an early cemetery and finds in the vicinity of the castle supports the suggestion that pre-urban settlements began in Norwich during the 8th century (Ayers 1994, p. 22). Indeed, small concentrations of Middle Saxon finds occur within the local ‘settlement’ area.

The two Burhs

Norwich’s emergence as a town may be rooted in the probable period of Danish occupation (c. 870 to c. 917) and in the Anglo-Scandinavian period that followed re-conquest by the West Saxon kings. The presence of a defended area of possible Danish origin on the north bank of the River Wensum (Northwic) was originally postulated on the basis of surviving street pattern (Carter 1978, fig. 7). This D-shaped enclosure may have been of similar character to those recorded elsewhere (such as Bedford and Lincoln), possibly re-used – as at Ipswich – to form a 10th-century burh (Ayers 1997, p. 59).

New information suggests that at Norwich two ‘burhs’ may have opposed each other across the River Wensum (Figure 1.3), similar double burhs being known at many urban centres such as Ipswich, Thetford and Cambridge. The limit of Norwich’s southern burh may be reflected in the curving line of Mountergate (formerly Inferior Conesford), running northwards across the cathedral precinct to meet the river just to the east of Whitefriars bridge (cf. Atkin and Carter 1985; Atkin 1993). An extension of this line to the west of King Street runs along the former course of Stepping Lane and Rising Sun Lane (cf. 1883 OS map), to the junction with Golden Ball Street. West of this point, the castle defences obliterated any topographical indicators of this putative boundary. The western limit of settlement was probably defined by the contours of the Great Cockey stream valley, its position mirroring the known defence on the river’s north bank. Recent work south of Stepping Lane confirms the presence of a substantial ditch in the anticipated position of the Late Saxon defence (Site 26577N; Penn 1999; Lloyd et al. 2002). Any continuation to the east and west has not yet been located, although a ditch and bank observed immediately to the west of the castle have been interpreted as demarcating the Castle Fee boundary and/or that of the burh (see below).

On the basis of the evidence summarised above, the burh ditch would be expected to have run directly across the Castle Mall site: although the recorded evidence provides no apparent evidence for its presence, a line across the western and southern part of the site was clearly significant and was repeated by the castle earthworks.

The Late Saxon town

Recent evidence has revised the plan of Late Saxon Norwich, with evident regularity to the east of King Street (Emery 2007), probably the result of the combined effects of local topography and proximity to the town’s economic centre (Figures 1.3 and 1.4). Whether this more regular settlement was established during the Late Saxon period or whether it was a post-Conquest development remains uncertain. Of course, such regularity does not necessarily imply planning as unplanned settlements (i.e. those not deliberately laid out as an entity) ‘could also appear regular owing to the constraints imposed by natural or relict features acting as morphological frames’ (Biddle 1975, p. 31). At the castle site, to the west of King Street, no planning is evident, with growth now being seen as a much more organic process rooted in the Middle Saxon period.

There is no specific indication of a high status area – possibly part of the demesne of the Earl of East Anglia, Ralph de Gael/de Guader – beneath the castle. Undoubtedly the 27 Late Saxon buildings found at Castle Mall correlate with some of the 98 houses or properties that Domesday Book notes were swept away by castle construction: ‘on that land of which Harold had the jurisdiction, there are 15 burgesses and 17 empty dwellings which are in the occupation of the castle. Also in the Borough there are 190 dwellings empty in this [area] which was in the King’s and the Earl’s jurisdiction and 81 in the occupation of the castle’ (Brown 1984, p. 116b (1.61)). Norwich is one of eleven towns recorded by Domesday as suffering damage, destruction or abandonment of buildings as a result of castle construction: at several other urban centr...