![]()

1. Introduction

Michael J Jones, Kate Steane and Alan Vince

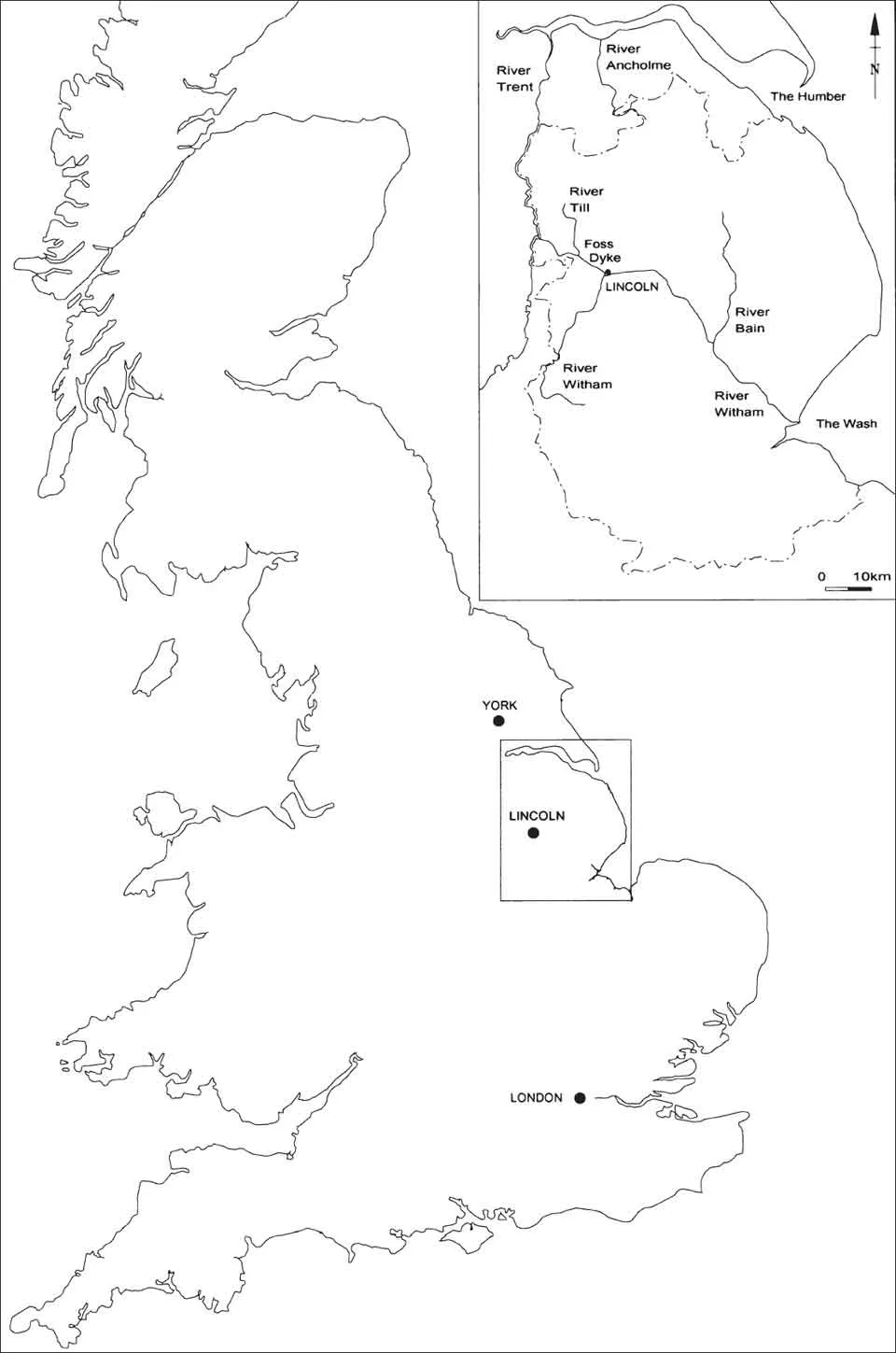

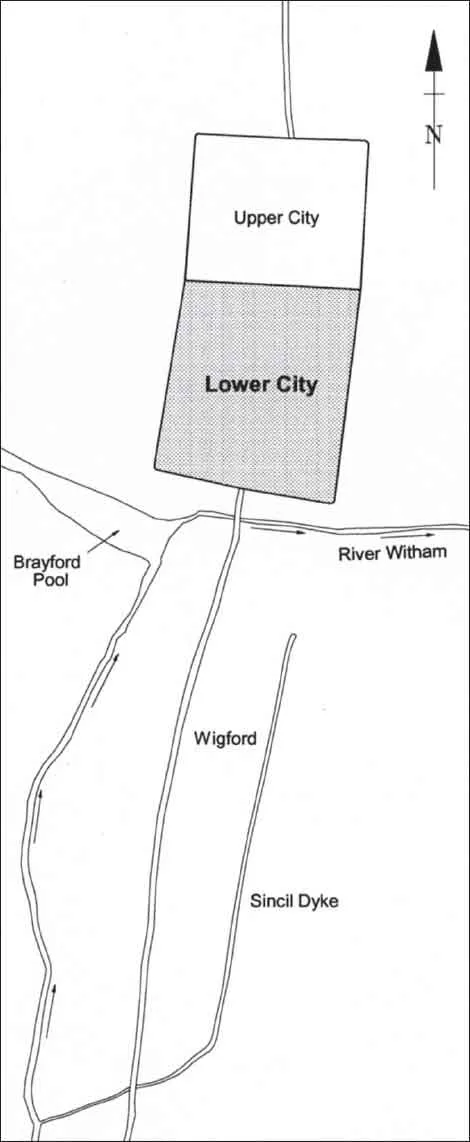

The geography and history of the Lower City (Figs 1.1 and 1.2)

The so-called Lower City of Lincoln that is the subject of this volume is situated immediately beneath the Lincoln Edge on the north side of the Witham Gap. Its present height above sea level rises from c 10m OD at the Stonebow, the position of its south gate, to c 60m OD at the entrance to the Upper City. Over most of the area, the ground-level has risen over the past 2,000 years or so by 3 to 5 metres, exceptionally in excess of 6 metres; higher up the steep slope, however, the need for terracing has resulted in there being cut as well as fill, and modern structures can lie directly over the natural subsoil. Close to the top of the hill that subsoil consists of stiff liassic clay. On the hilltop itself, the clay lies beneath a cap of limestone and ironstone, but on the hillside the clay outcrops, often with springs within it. Lower down, on the gentler slope, the clay is sealed by sand and gravel terraces extending to the River Witham. An illustration by the local antiquarian Michael Drury of the strata noted during the laying of sewers in the 1870s suggests that the river may actually have extended to the north of what became the southern line of the Roman fortifications (Drury 1888).

As a background to the excavation reports contained in this volume, we present here a summary of the state of knowledge of the history and archaeology of the Lower City at the start of the major campaign of rescue work that effectively began in 1970. Its historic nature was long apparent from the survival of important medieval monuments, and even parts of the Roman city wall into the 19th century (Stukeley 1776), but no systematic archaeological work had taken place in the Lower City before 1945. As excavations got under way that year at Flaxengate, in preparation for the summer meeting of the Royal Archaeological Institute at Lincoln in 1946, Ian Richmond published the evidence (much of it collected locally by F T Baker) for the city’s Roman occupation (Richmond 1946). He noted with characteristic acuity that the existence of cemeteries to the south of the river suggested that occupation on the hillside (the ‘enlarged colonia’) began at an early stage in the Roman occupation and that there must have been intensive ribbon development along Ermine Street to the south of the Upper City. What was seen initially as a ‘suburb’ became ‘so essential a part of the town’ that it was rationalized and fortified. The line of those defences was traceable from antiquarian discoveries, and similar sources indicated to Richmond the existence of terrace walls on the steeper hillside, and some monumental buildings further down. In the same year that major excavations commenced at The Park, Ben Whitwell’s newly-published survey in 1970 (rev edn 1992) was only able to add more details of the city wall, elements of successive town-houses east of Flaxengate (Coppack 1973a), and an octagonal public fountain at 291–2 High Street (Thompson 1956). While there was some uncertainty about the composition of its inhabitants and its exact legal status, ie, whether it was originally designated as a vicus rather than being part of the colonia from the outset (eg, Wacher 1995, 142–3), the results of excavation were corroborating Richmond’s view that the Lower City was planned as an integral part of the Roman city from an early date (eg, Esmonde Cleary 1987, 108–10).

The concentration on Roman remains and research objectives to the detriment of later (and earlier) periods was a feature of the era up to 1970, although the city had already been blessed with a detailed history of the medieval period by Sir Francis Hill (1948), followed in due course by three further volumes that covered its history to the end of the Victorian period (Hill 1956, 1966, 1974). In the absence of detailed historical and archaeological records, the Anglo-Saxon period could only be discussed by Hill in relatively brief terms, but a useful start was made in attempting to understand the topography of the pre-Conquest town. In addition to the documentary history now set out so articulately, the medieval heritage of the hillside was clearly apparent from some remarkable physical survivals: two Norman houses on the main street, and the Franciscan friary squeezed within the walls, as well as the important civic symbols of the Stonebow and Guildhall. The Lower City had clearly played a significant role in the life of the medieval city. That presumably was the case for at least a century before the Norman Conquest, when it already was the principal centre in the East Midlands, and even in the later medieval periods.

Fig. 1.1. Location map of Lincoln, with inset showing principal river-system of the county.

Fig. 1.2. Location of the Lower City within the historic core.

Although Hill’s books made it a much simpler task to undertake research on the topography of the medieval and later city, the pits discovered to the rear of their associated properties on the medieval street frontages and cutting into the remains of the Roman house at Flaxengate in 1945–7 were not considered to represent sufficient interest for the site to be further investigated in advance of the car park built there in 1969. It was still common to remove post-Roman deposits mechanically with only the most cursory monitoring. Yet Lincoln had long been producing some outstanding medieval artefacts: before 1848, when it was exhibited, a ridge tile with a unique bifacial head had been found, while in 1851 a remarkable Anglo-Scandinavian antler comb case with a runic inscription turned up near to the present railway station (Barnes and Page 2006, 292–5). The new era of professional field archaeology that was to begin in 1970 would help to make up for those deficiencies, and establish beyond doubt the richness and value of the post-Roman deposits. In this endeavour, we were helped by the exemplary work of Kathleen Major on the cathedral cartulary, the Registrum Antiquissimum, that covered some of the parishes in and adjacent to the walled Lower City (Major (ed), 1958, 1968, 1973). It was also during the 1970s that Kenneth Cameron began his long campaign on the place-names of the county, the City of Lincoln volume being the first to be published (1985), and another invaluable aid to archaeological research.

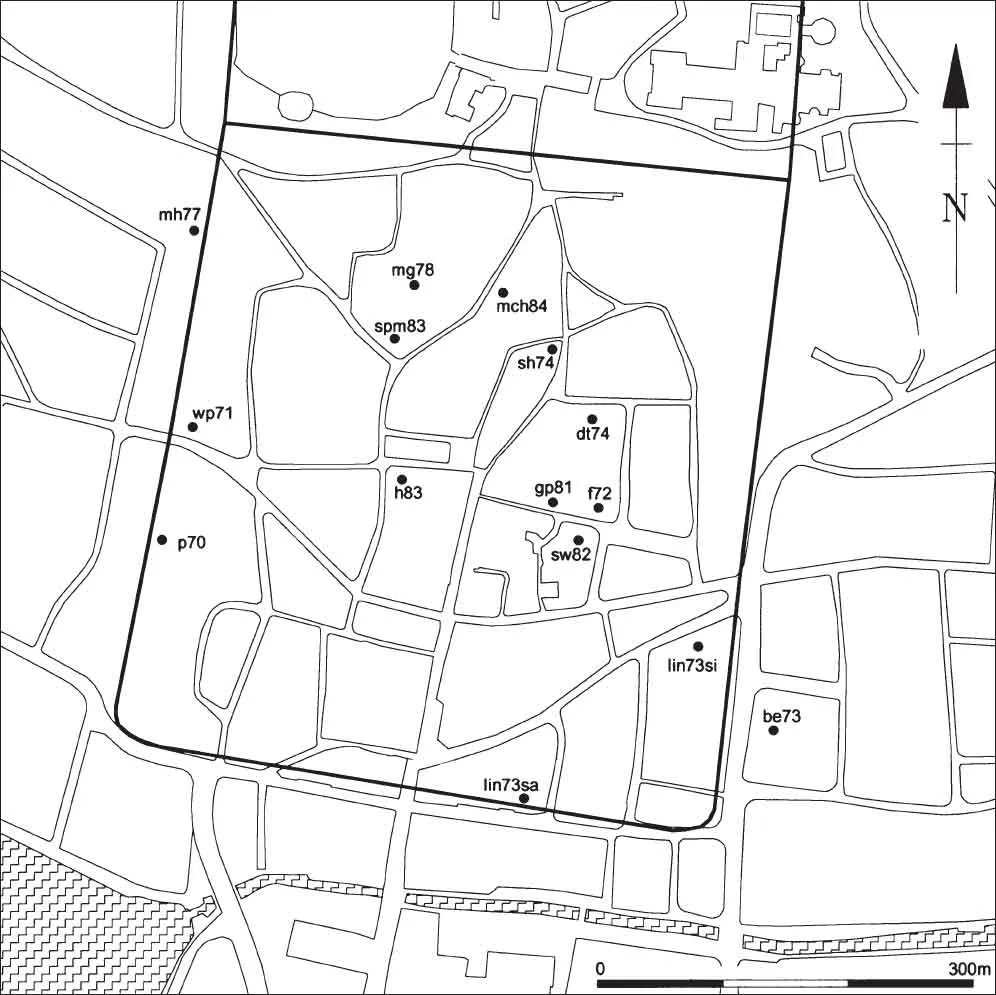

Excavations (Fig. 1.3)

The sites published here were excavated between 1972 and 1987. In the text they are frequently referred to by their codes (eg, f72 for the Flaxengate excavations that commenced in 1972). This particular site was a proposed Crown Office development on the line of the projected third phase of the Inner Ring Road that was in the event never constructed; while the road was still a current proposal, property on its line, including the Hungate site (h83), was blighted. Otherwise residential and commercial developments were the major reasons for the archaeological investigations, and the hillside has continued to see further development of this nature since. The commercial schemes, like Saltergate (lin73sa), tended to be those in the southern part of the area, closer to the commercial centre, and they included a multi-storey car park east of Broadgate (be73). With the vagaries of the economy generally and the property market in particular, including an acute crash in 1973–4, some of the proposed schemes were delayed until several years after the excavations had been (in some cases hurriedly) completed; others never materialised at all. Some sites were investigated for assessment purposes. The excavations varied in the extent and depth of the stratigraphic sequence uncovered, and each had a different period emphasis. In some cases (eg, Danes Terrace: dt74), the investigations were not planned or allowed to penetrate to the earlier levels. The relatively short distances between some of the sites, however, offered possibilities for understanding archaeological sequences and the changing topography across a wide area of the Lower City (Fig. 1.3). The principal gaps are the High Street frontage and the north-eastern quadrant – although a corner of this was, and still is, occupied by the medieval Bishop’s Palace. This monument has been the subject of a repair scheme by English Heritage (Coppack 2002), supported by detailed survey work undertaken by the City of Lincoln Archaeology Unit in the early 1990s.

Fig. 1.3. Location of the Lower City sites analysed in this volume, also showing The Park (p70) and West Parade (wp71).

A number of individuals, sometimes more than one per site, oversaw the various excavations. They included Tom Blagg (f72), Kevin Camidge (mg78, h83), John Clipson (f72), Christina Colyer (f72), John Farrimond (spm83), Brian Gilmour (f72), Michael J Jones (f72, dt74, be73), Robert Jones (f72, dt74, sh74, mh77, be73), Nicholas Lincoln (sh74), John Magilton (sw82, spm83), Colin Palmer-Brown (sh74), Dominic Perring (f72, mh77), Nicholas Reynolds (lin73sa, lin73si), Andrew Snell (mch84, spm83), Geoff Tann (gp81), Michael Trueman (spm83), John Wacher (overall direction of lin73sa, lin73si), Richard Whinney (dt74), Douglas Young (spm83), and Robert Zeepvat (lin73si). These staff worked on behalf of either the local Archaeological Society (Lincoln Archaeological Research Committee to 1974; Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology from 1974), for the Lincoln Archaeological Trust (1972–84) or its successor bodies, the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology: City of Lincoln office (1984–8), later the City of Lincoln Archaeology Unit. In the case of the Silver Street and Saltergate sites (lin73si and lin73sa) the employer was the Department of the Environment’s Ancient Monuments Branch.

Funding for excavations between 1972 and 1987 nearly always came from more than one source. Central Government, in the form of the Department of the Environment, and, from 1984, via its agency English Heritage, made the major contribution to the costs. Initially, Lincoln County Borough Council, and then Lincolnshire County Council, which serviced the Trusts between 1974 and 1988, also provided some funding, but always a relatively small proportion. The Manpower Services Commission provided some of the costs of the excavation teams for several sites during the 1980s.

Previous publications for most of the sites included preliminary accounts in the annual reports of the Lincoln Archaeological Trust (1972–84) or those of the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology (1985–8). An interim report about discoveries between 1973 and 1978 was also published in The Antiquaries Journal (Colyer and Jones (eds) 1979), and a summary appeared each year in the county journal, Lincolnshire History and Archaeology. Among the fourteen reports in the Archaeology of Lincoln series that appeared in the period 1973 to 1991, quite a number covered aspects of the post-Roman discoveries at the Flaxengate site (f72). These dealt with structures as well as finds and animal bones from the important Late Saxon and medieval deposits here (R H Jones 1980; Perring 1981; Mann 1982; O’Connor 1982; Adams Gilmour 1988), while the coins from this site provided the basis for a report on Late Saxon and early medieval numismatics from Lincoln and its hinterland (Blackburn et al 1983). Others dealt with the medieval pottery from Broadgate East (Adams 1977) and that from the Late Saxon kilns at Silver Street (Miles et al 1989). Full details are listed in the Bibliography.

Archiving and post-excavation analysis

In 1988 English Heritage commissioned the City of Lincoln Archaeology Unit to undertake the Lincoln Archaeological Archive Project over a three-year period to computerise the existing records for sites excavated in the period 1972–1987; this project was managed by Alan Vince. The records were listed in detail, suitable for permanent curation, while their computerisation was also intended to facilitate future research and decision-making (see Appendix I for details).

In 1991, the potential of the sites was assessed and a research design for the analysis and publication of their excavation was presented to English Heritage (Vince (ed) 1991); among the publications proposed was the present volume. A first draft of the report text was submitted to English Heritage in 1998. English Heritage subsequently commissioned alterations and a more systematic and formalised structure, on the recommendations of Steve Roskams of the University of York, the academic adviser. Kate Steane began the job of co-ordinating the major reordering of the stratigraphic data in line with these recommendations; it was later taken over and completed by Michael J Jones, who had meanwhile replaced Alan Vince as project manager on the latter’s departure to another post. He has subsequently undertaken both academic and copy-editing of this report, along with a huge amount of input and support from Jenny Mann.

The stratigraphic framework: rationale

Each site narrative is an attempt to present an interpretation of what took place through time, backed by an integrated analysis of the evidence. The primary framework is stratigraphic; within this framework the pottery and other finds have specific context-related contributions with regard to dating, site formation processes, and functions.

The stratigraphic framework has been built up using the context records made on site to form a matrix. The contexts, set into the matrix, have been arranged into context groups (cgs); each cg represents a discrete event in the narrative of the site. The cgs have been further grouped into Land Use Blocks (LUBs); each LUB represents an area of land having a particular function for a specific length of time. The move from contexts to cgs, and in turn to LUBs indicates a hierarchical shift, from recorded fact to interpretation, from detail to a more general understanding of what was happening on the site. Here the cgs are the lowest element of the interpretative hierarchy presented in the text.

The LUBs are presented chronologically by period and each site is provided with a LUB diagram, so that the whole sequence of LUBs can be viewed at a glance. Because it is near to the top of the interpretation hierarchy, the LUB depends on the stability of the context group structure and this in turn depends on the strength of the dating evidence.

Within the text each Period (see below, with Fig. 1.5) has a LUB summary, so that it is possible to move through the text from period to period in order to gain an outline summary of each site sequence.

Structure of this publication

The organisation of the volume originated from the initial authorship of the first drafts of the site narratives written as part of the Archive Project. The order of their presentation does not follow that of their alphabetical codes, but they appear mainly in three linked groups: first those in the Flaxengate/Grantham Street area, then the two sites along Silver Street, and finally those on the steeper slope. The final site (be73) lay outside but adjacent to the fortifications of the Lower City. Each site narrative is m...