![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Rock art in south-east Scania

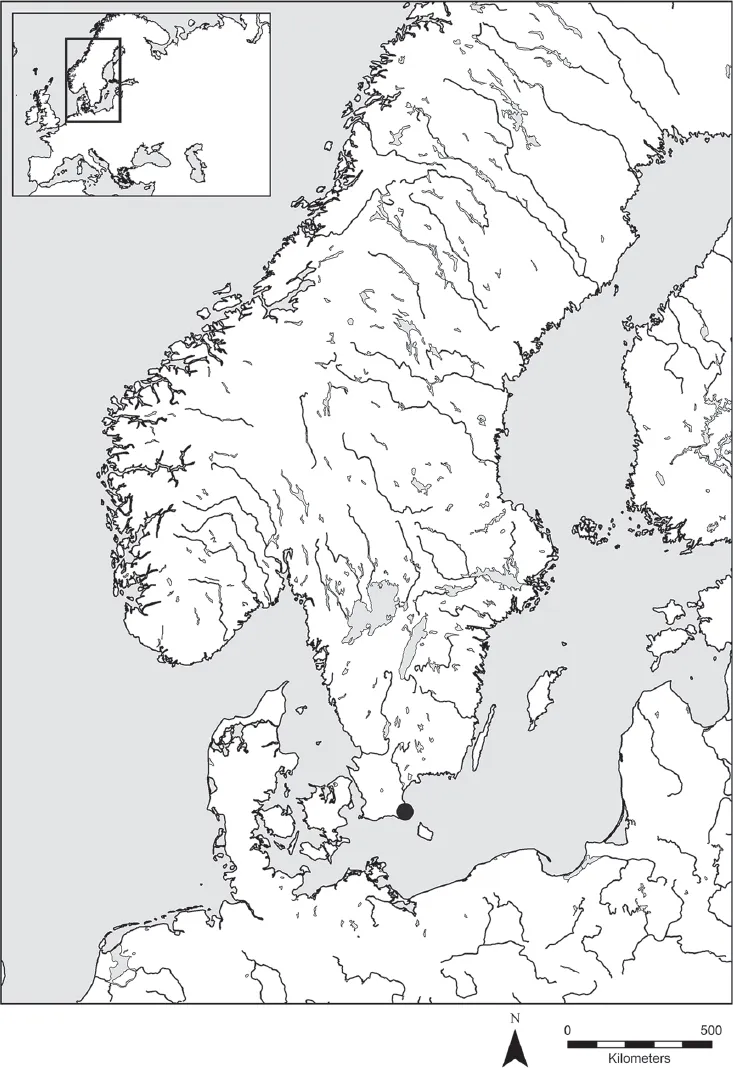

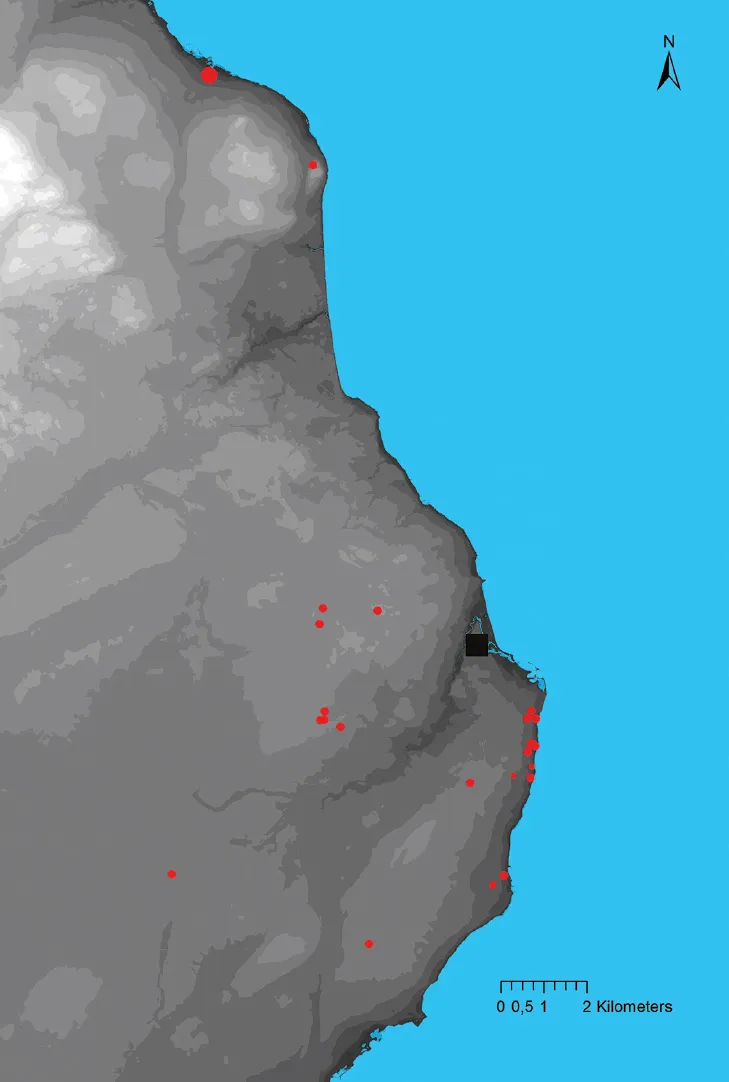

This book deals with the rock art surrounding the city of Simrishamn in south-east Scania, Sweden (Fig. 1.1, 1.2). As many other areas in south Scandinavia, this region has a great many Bronze Age mounds that are still visible in the landscape, and records from the museums demonstrate that the area is rich in bronze metalwork (Larsson 1986).

Nevertheless, it is the figurative rock art that makes this region stand out as distinct in relation to surrounding areas that lack figurative images. The rock art in this region constitutes a spatially well-defined tradition that chronologically covers the Bronze Age and the earliest Iron Age, c. 1700–200 BC (Althin 1945; Skoglund 2013a). Even though the number of sites is limited, they have certain characteristics that are stimulating starting points in any attempt to interpret south Scandinavian rock art.

One feature distinguishing this region from many other regions is the larger representation of various kinds of metal axes, offering an opportunity to compare images and objects from different perspectives.

Another characteristic is the geographical position of this area, inside the core zone of metal consumption in southernmost Scandinavia. In this respect the Simrishamn area is rather unique as the majority of rock art regions in Scandinavia are located further north in zones where there was less metal in circulation. Therefore, we may presume a closer relationship between iconography displayed on metals and iconography displayed on rock art in the Simrishamn area than what is generally found when dealing with Scandinavia as a whole.

Figure 1.1. Map of Scandinavia with the studied area indicated by a black dot. Image: Tony Axelsson.

The Simrishamn region encompasses a limited number of rock art panels compared to most other south Scandinavian rock art regions. Instead of being a restraint, this could be seen as an advantage; motifs executed early in the tradition of rock art are only to a limited degree blurred by later additions.

Figure 1.2. Map of the study area with rock art panels indicated by red dots and the city of Simrishamn indicated by a black square. Image: Peter Skoglund.

Finally, the Simrishamn region is situated in Scania, a region which is quite well understood from an archaeological perspective, as many large-scale rescue excavations have been carried out in connection with the expansion of towns and the construction of new railways and motorways. Thus, there is good potential for relating rock art to a wider archaeological framework.

It should be noted, however, that there are problems involved in the interpretation of the rock art in this area. A fundamental concern is the spatial distribution of rock art, which is biased because of modern activities: especially the frequent occurrence of stone quarries close to rock art sites has caused severe damage. The majority of the rock art in south-east Scania is carved on Cambrian sandstone, which seems to have been in high demand among the local people in older times.

At the two major rock art sites, Simrishamn 18:1 and 23:1, for example, it is evident that these recent activities have destroyed rock art. Another factor to consider is the location of modern communities like the village of Brantevik, which to a large extent is situated on rocky ground. Rock art sites are known just outside the village (Östra Nöbbelöv 85:1, 127 and 129) and if there once existed sites closer to the sea in the present-day village these are gone today.

Despite these shortcomings, the Simrishamn area is a good starting point for a study of south Scandinavian rock art, and though this book deals with a restricted region, the aim is to raise some questions of principle concerning the current understanding of the south Scandinavian rock art tradition.

Earlier research on rock art in south-east Scania

The aim of this section is to give a brief survey of earlier research on Scanian rock art and its relation to the present study.

The study of Scanian rock art started with the discovery of the Kivik carvings in the mid-18th century; and since then a large amount of research has been devoted to the Kivik cairn including its carvings. However, it is only recently that the Kivik monument has been the subject of an extensive biography, written by Joakim Goldhahn, which also includes an overview of earlier research (2013). The reader is referred to that publication and Klavs Randsborg’s study from 1996 for an account of the Kivik carvings. A new documentation of the carvings was conducted in 2014 by Andreas Toreld and Tommy Andersson (Toreld and Andersson 2015).

The Villfara carving was found in a grave context in the 1820s – this monument too has attracted a lot of interest, and a reinterpretation of the carving including an evaluation of earlier research was recently published by Jens Winther Johannsen (2013).

The start of more general interest in south-east Scanian rock art goes back to the 1850s when Nils Gustaf Bruzelius – an archaeologist educated at Lund University – started to recording rock art and perform archaeological excavations in the Simrishamn area. He visited several panels around the city of Simrishamn, spoke to the local people and in 1875 he wrote the first scholarly synthesis of the rock art in the area.

He spotted all the larger sites known today (Simrishamn 15:1 and 23:1 and Järrestad 13:1), and several smaller ones as well. In order to date the carvings at Järrestad 13:1 he performed archaeological excavations of nearby mounds. In his published work he primarily operated with written descriptions, but he also published some drawings (Bruzelius 1880–82).

The first large work including documentation of all known Scanian rock carvings appeared in 1945 when Carl-Axel Althin published his doctoral thesis Studien zu den bronzezeitlichen Felszeichnungen von Skåne 1–2. Althin’s main focus was to date the Scanian carvings, and by using a comparative method whereby he examined rock art motifs in relation to metalwork, he concluded that a majority of the carvings dated to Montelius’ periods IV and V. His work has been criticized both for the specific interpretations of motifs and for the chronological framework (Nordén 1946; Burenhult 1980: 101–103), but to this day it has remained the only in-depth study of the Scanian rock art.

A major problem with Althin’s study is that even though he compared rock art images with actual artefacts, he disregarded many of the axes at Simrishamn 23:1 because he thought of them as being over-dimensioned cult objects made of organic materials. The majority of scholars both before and after Althin have regarded these axes as flanged axes (Montelius 1900; Burenhult 1980; Almgren 1987). Due to this standpoint, Althin missed out the early phase of Scanian rock art, and reached the conclusion of a Late Bronze Age origin for a majority of the images.

In 1974 Stig Welinder published an article on Scanian rock art, where he discussed the combination of motifs on different sites in order to gain an understanding of the chronology. According to Welinder, there were three traditions with different datings. The oldest one was made up of axes and ships which ceased to be produced during Montelius’ period III, the second one consisted of circle motifs and wagons which had a long period of production covering the whole Bronze Age, and the latest tradition consisted of feet images which Welinder attributed to the latest part of the Bronze Age (1974: 272–273).

Scania was crucial for Göran Burenhult in his work on the chronology of the south Scandinavian rock art and he criticized Althin for the conclusion that a majority of them originated in Montelius’ periods IV and V. Instead of Althin’s comparative method, he used carving depth as a chronological criterion, and by this method he established an alternative foundation for the dating of rock art. He concluded that the start of the rock art tradition was in the Middle Neolithic, but he regarded the major rock art tradition as being of Early Bronze Age date (1980). This conclusion was reached primarily on the basis of carving depth, but he also compared images of artefacts with actual artefacts. Burenhult’s methodological approach has been criticized (Mandt 1982), and has not been widely accepted.

The Scanian carvings were also important to Bertil Almgren, who based his conclusions about rock art chronology on a comparison of style in carvings and style in the design of metal objects (1987). Almgren argued that the Scanian rock art tradition covered a longer period of time including the whole of the Bronze Age. Though Almgren’s methodological approach is difficult to grasp in all its nuances, his conclusions on chronology are very often in line with present-day research.

Lately, important work has been carried out by John Coles on the Järrestad carving. Especially noteworthy is the re-documentation of this large and important panel (1999).

In 2004 Christopher Tilley devoted substantial parts of his book The Materiality of Stone to the study of rock art in south-east Scania. The chronology of individual panels was not an issue for Tilley; he was interested in the wider context of the carvings, such as their relation to the sea and surrounding monuments.

Over the years there have been several projects aiming at documentation of individual sites. In the 1980s a large panel came to light in the ground of a private house at Brantevik and a preliminary account on this site was given by Märta Strömberg (1985). New documentation of several panels has also been carried out by Sven-Gunnar Broström and Kenneth Ihrestam, both in relation to a survey of ancient monuments conducted by the National Heritage Board (2011) and as part of the present project (2013a, 2013b, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c). Rock art panels have also come to light at Brantevik as a result of archeological excavations (Wallin 2010). Recently, a group of German researchers undertook new documentation of the panel at Simrishamn 15:1 (Tron et al. 2007). Finally, the Swedish Rock Art Research Archive in Tanum has managed intensive fieldwork and documentation of the larger panels at Simrishamn 23:1 and Järrestad 13:1. The recording is displayed at the website www.shfa.se.

This study shares an overall interest in chronology with the works of Althin, Burenhult and Almgren. In contrast to Burenhult, I do not see any clear evidence of a Neolithic beginning of the rock art tradition, but the figurative motifs have parallels in Bronze Age material culture.

Methodologically, this study operates in line with Althin’s comparative approach, studying rock art in relation to the design of metal artefacts and motifs occurring on metal objects. Althin made important observations, but his results are constrained by the notion that he thought each panel represented a rather closed moment of time: he was unwilling to accept that a single panel could have been used during different periods of the Bronze Age. That many of the panels in south-east Scania were used during different periods was demonstrated by Bertil Almgren (1987), and a multi-period use of many panels in south-east Scania is consistent with the results of this study (Skoglund 2013a).

This study chiefly differs from earlier ones because of the ambition to put rock art into a rather detailed historical context. In this discussion the notion that rock art panels were part of a cultural landscape that underwent significant changes during the course of the Bronze Age is important. These two starting points – rock art chronology and landscape perspectives – will be elucidated in the coming sections, but first a short note on the organization of the present project is necessary.

Methods used in the present project

This study is the outcome of a research project organized by the Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (SHFA) in Tanum, Sweden. The project was set up to provide a detailed chronological evaluation and interpretation of a Scandinavian rock art region. Through Ulf Bertilsson the SHFA has been running a documentation project in south-east Scania for many years, and the present project is indebted to these efforts that have concentrated on the larger Simrishamn 23:1 and Järrestad 13:1 sites.

At an early stage it was noted that, in order to work with the region as whole and not specific sites, there was a need for additional documentation of the smaller sites that have not been in focus in earlier research. Therefore the reputable rock art surveyors Sven-Gunnar Broström and Kenneth Ihrestam were attached to the project.

The following sites were visited and documented together with Broström and Ihrestam: Gladsax 8:1, 9:4, 90:1, Simrishamn 2:1, 12:1, 16:1, 18:1, 20:1, 22:1, 29, 45 and Östra Nöbbelöv 85:1. Broström and Ihrestam were in charge of the actual documentation and for a detailed account the reader is referred to their reports (Broström and Ihrestam 2013a, 2013b, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c).

When the individual motifs had been identified, sometimes using light at night-time, they were painted with limewash and then the motifs were transferred to plastic film. Later on the plastic film was reduced in scale and transferred to paper. The documentation was supplemented by written descriptions and photos.

An additional but important outcome of this documentation project was the possibility to visit and discuss rock art panels with colleagues who have extensive experience of rock art surveying. My understanding of specific motifs and their setting on the panels, and the wider landscape context, has improved thanks to this joint project. In addition to the drawn documentation, the photographs taken of the motifs painted with limewash are also an important source material, and some of these are included in this book.

The author himself has also visited and taken notes of all those sites that contribute to the chronological scheme visualized in Figure 2.36.

Based on records provided by the Archaeological Sites and Monuments database www.fmis.se (often referred to simply as FMIS or Fornsök) a database was set up which is the foundation for the distribution maps of rock art panels displayed in the book. Throughout the book there will be references to individual sites using the name of a parish followed by a number; for example Järrestad 13:1. This way of organizing archaeological sites and monuments has a long tradition in Sweden and it refers directly to the National Heritage Board’s database FMIS.

Rock art chronology

According to the recent chronologies, rock art was produced in south Scandinavia for a period of some 1,500 years from 1700 BC to 200 BC (Kaul 1998; Ling 2008). Thus chronology is a major obstacle when interpreting rock art images. As some of the open-air sites were used repeatedly for a period sometimes approaching 1,500 years, it is sometimes difficult to work out which images are contemporary. To overcome this problem, depictions on the rock carvings have been compared to metal items that are associated by find context with the chronological scheme worked out by Oscar Montelius in the 1880s (Ekholm 1916, 1921; Almgren 1927; Fett and Fett 1941; Althin 1945; Marstrander 1963; Glob 1969; Mandt, 1991; Rostholm 1972; Malmer 1981; Kaul 1998, 2003, 2004, 2006; Sognnes 1993, 2001; Nordenborg Myhre 2004).

Even though this research tradition goes far back in t...