![]()

PART ONE

THE BACKGROUND REVIEWED

At Crow’s Nest: loking north towards the Vale of Montgomery and the Berwyn Mountains

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Offa’s Dyke in profile: character, course and controversies

King Offa, in order to have a partition for all time between the Kings of England and Wales, built a long dyke stretching from the south past Bristol, along the edge of the Welsh Mountains…. This dyke is still to be seen in many places.

(William Caxton, The Description of Britain, c.1480)1

The building of Offa’s Dyke is rightly regarded as being among the greatest physical achievements of the inhabitants of the British Isles during the period between the end of Roman Britain and the Norman Conquest. The most obvious characteristics of its great length and its crossing of hilly ‘border’ country have been understood in detail for at least 200 years.2 The Dyke was, moreover, the subject of one of the first extended studies in what has come to be termed ‘landscape archaeology’. Sir Cyril Fox made a detailed study of the earthwork, along with Wat’s Dyke which runs parallel to it in the northern part of its course, in a major survey project undertaken in the period 1926 to 1934. This was published in a substantial monograph in 1955, bringing together his earlier work and providing a strong evidential basis for subsequent discussion. Fox’s interpretation of the Dyke as, in effect, the product of negotiated treaty relations between Mercia and the Welsh kingdoms neighbouring it to the west, held sway for a generation. Yet although there has subsequently continued to be broad agreement concerning the identity of the Dyke as a ‘frontier work’ associated with the zenith of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, and with the eighth-century kingship of Offa in particular, there have remained questions concerning its exact date and purpose, doubts expressed about its extent, and discussion also concerning the organisation of its construction.3

There are a number of questions that can be posed concerning the basic characteristics of Offa’s Dyke, such as ‘what is the nature of the linear earthwork?’, and ‘what condition is it in?’, and the answers to these are set out briefly here. Further questions have been asked ever since the Dyke became an object for serious historical study, at least since the nineteenth century. Prominent among these are ‘when was it built?’, and ‘can it definitely be attributed to King Offa?’ A number of features of the Dyke have been questioned, and paradoxes identified, chief among which are ‘what is the significance of the apparent gaps in its course, and are they real or illusory?’, and ‘what is its relation to Wat’s Dyke and other linear earthworks in the Marches of Wales?’ These and related questions are explored here, not at this stage in the book necessarily to provide detailed answers but rather to indicate the extent and limitations of current knowledge. Finally, as a prelude to detailed analysis of its location in the landscape later in the volume, a full description of its course is provided here, northwards and then southwards from the middle Severn valley near Welshpool in the present-day Welsh administrative region of Powys.

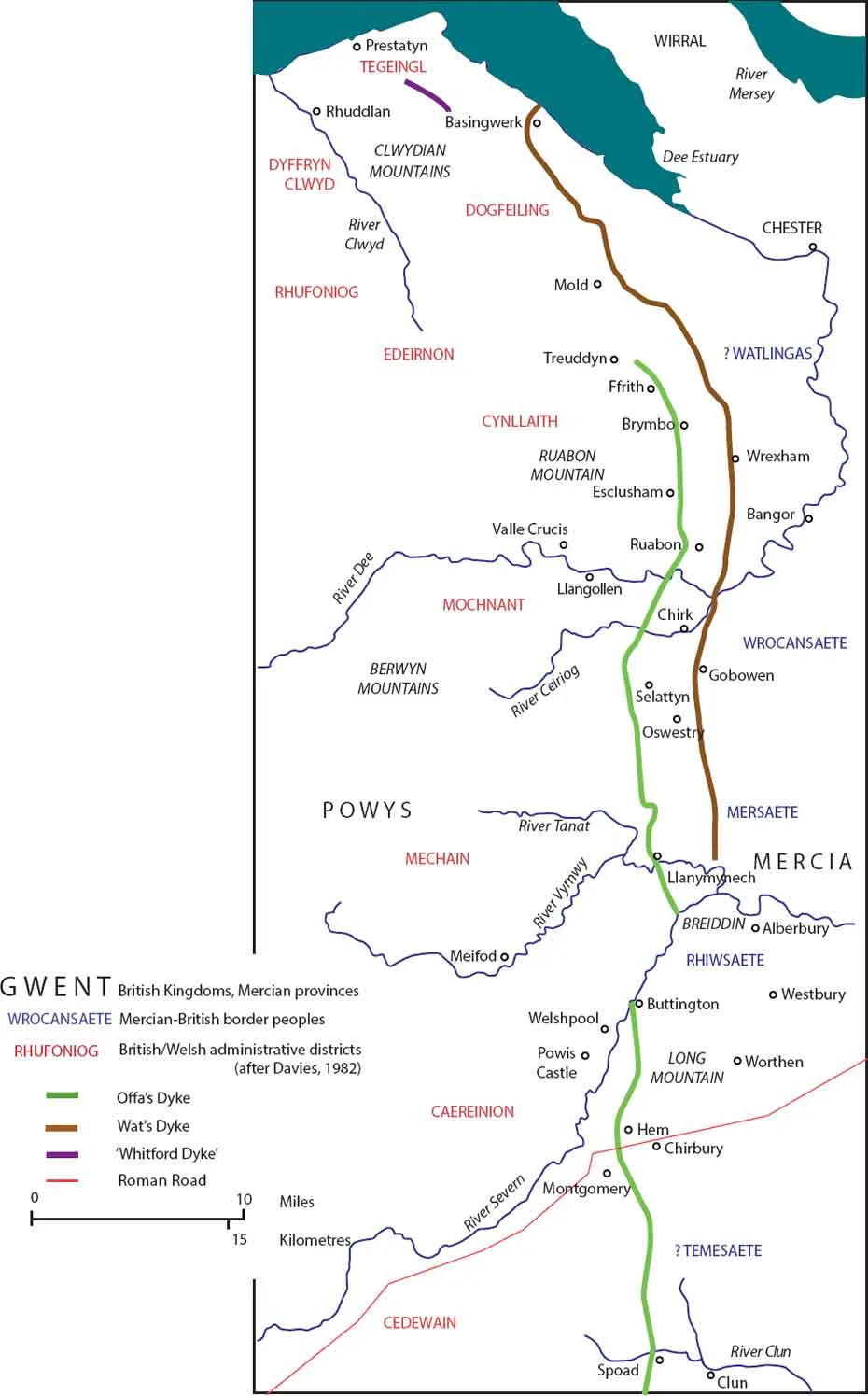

FIGURE 1.1 Offa’s Dyke and Wat’s Dyke in west-central Britain

Note especially the contrast between the location of Offa’s Dyke in the upland margins and Wat’s Dyke in the plain, and the differences between the line of Offa’s Dyke and the modern Wales/England border.

An introductory characterisation

Visible today as a sometimes prominent feature in the landscape, Offa’s Dyke is a very long distance linear earthwork that crosses often deeply dissected terrain just beyond (that is, to the west of) the western margin of the lowlands of ‘west-central’ southern Britain, and of the English Midlands. The Dyke follows a carefully placed north–south route, holding closely to this primary orientation throughout much of its known course. The basic structure comprises an earthen, or earth and stone, bank with a ditch dug (mostly) on its western side, such that the earthwork faces westwards (Figure 1.2). A substantial counter-scarp bank is present on the outer lip of the ditch along enough well-preserved stretches to indicate that this was a commonly-occurring original construction feature.4 On the eastern side of the bank there are pits, or a west-facing scarp, or occasionally a linear quarry, or (more frequently than has been widely acknowledged) what appears to be a continuous ditch, from which contributory material to build the bank was derived. In some locations more than one of these features co-exists.

FIGURE 1.2 Offa’s Dyke at Mainstone, Shropshire, looking north

This length of Dyke, viewed northwards as it descends to the crossing of the upper Unk valley just to the south of the Kerry Ridgeway (and close to Crowsnest, shown in Figure 1.2), illustrates the basic features of the Dyke, with a continuous west-facing profile extending down into the base of the ditch on the western side of the earthwork; and with a prominent bank to the east. The way in which the Dyke approaches the valley here is discussed in Chapter 4.

The Dyke so constituted survives remarkably, if variably, well despite many centuries of natural erosion and human disturbance to its form and course. As will be described in subsequent chapters, the form of the Dyke exhibits variety but not inconsistency: there are design characteristics in both its positioning in the landscape and its built features that recur throughout its known course. Moreover, this recurrence of key locational and build characteristics of the Dyke is far from random. It represents, rather, a consistency also in how these features were deployed: both in response to the similarities in the topographical circumstances that were encountered, and in order to achieve particular effects.

The mid-way point along the 115 miles (185 km) span of the putative western frontier of Mercia from the North Wales coast to the Severn Estuary is at the valley of the river Clun, and this is the mid-way point today of the Offa’s Dyke Path. However, no definite trace of the upstanding earthwork Dyke has been recorded northwards of Treuddyn near Mold in Flintshire. Its last, impressive, length lies between Treuddyn and Llanfynydd, and it extends across 29 miles (c.47 km) or so southwards of this to the middle reaches of the river Severn to the north-east of Welshpool.5 Across this distance it is mostly continuous, although there are gaps where it has never been traced (as for example short stretches on the north banks of both the Dee and Ceiriog), and where it once existed but has either been quarried away or levelled due to historically-recent activity, as at several points in the Trefonen area south-west of Oswestry. The river Severn stands in place of the Dyke for 5 miles (8 km) southwards from a point near Rhos, to the north-east of Welshpool. Then the earthwork appears again on the margins of the floodplain of the Severn upstream at Buttington (and immediately to the east of Welshpool). It continues southwards from this location as a mostly substantial earthwork for another 28 miles (c.45 km) to Knighton at the crossing of the Teme valley, via the Vale of Montgomery and the Clun uplands.

From Knighton the Dyke continues as a linear earthwork largely without gaps for around a further 8 miles (c.12.5 km) as far south as Rushock Hill in north Herefordshire.6 Cyril Fox, in common with several among the earlier commentators, regarded a series of short lengths of linear earthwork in northern Herefordshire as having formed elements in a frontier line projecting the course of Offa’s Dyke southwards from Rushock Hill to the north bank of the river Wye near Bridge Sollers.7 Beyond Bridge Sollers, eastwards and then southwards mostly on the left bank of the Wye, further intermittent lengths of dyke or bank have been claimed at one time or another as part of Offa’s Dyke: although there has been little support for the idea that these ever formed part of the long-distance work.8

Across the 25 or so miles (c.40 km) involved, past Hereford, Fownhope, Ross-on-Wye, and Monmouth, only one of these claimed lengths has ever, it seems, been closely assessed. This particular short stretch, west of Lower Lydbrook in English Bicknor parish, has been positively identified in recent years as forming a coherent and characteristic length of Offa’s Dyke.9 Finally, from near Lower Redbrook in Gloucestershire, some 2 miles (3.2 km) to the south-east of Monmouth, and again on the left bank of the Wye, the earthwork resumes as a continuous or near-continuous upstanding earthwork, again with an admixture of contrasting scales of build. This stretch extends southwards, again on a north–south course, for around 10 miles (16 km), with localised gaps north and south of Tutshill (within Tidenham parish on the left bank of the Wye opposite Chepstow), some of which were caused by quarrying and others possibly by modern development.10 Close to the confluence of the Wye with the Severn the earthwork turns suddenly south-eastwards to cross the Beachley peninsula, where it terminates dramatically on the cliffs above the Severn Estuary (Figure 1.5).

FIGURE 1.3 The northern course of Offa’s Dyke south to the Clun valley, and Wat’s Dyke

Showing prominent mountains and hills, selected Welsh districts and cantrefs documented before AD 1200, putative Anglo-Saxon/British hybrid ‘peoples’ under Mercian authority (documented from Domesday and other sources), and the kingdoms of Mercia and Powys.

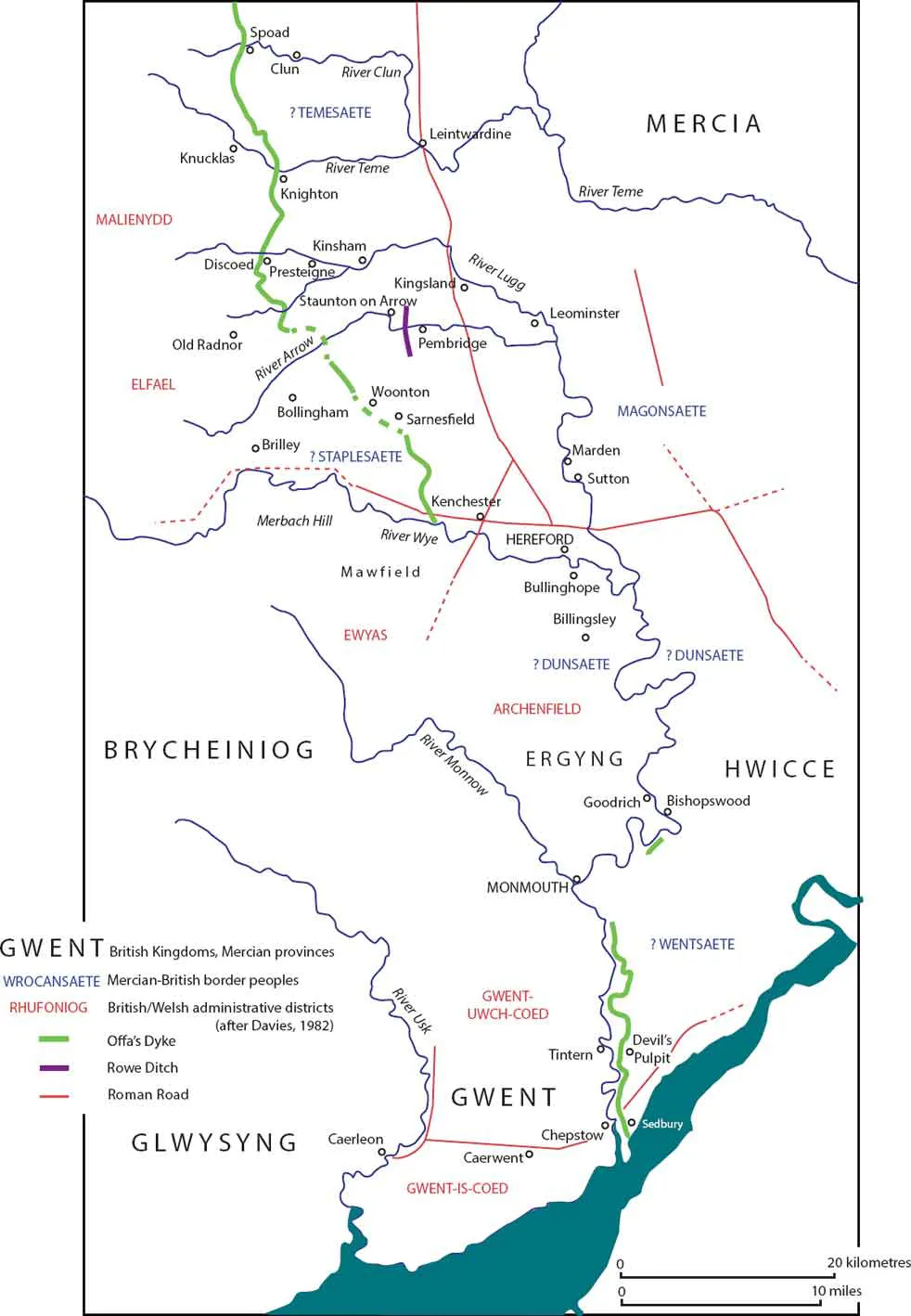

FIGURE 1.4 The southern course of Offa’s Dyke, south from the Clun valley to the Severn Estuary

Showing prominent mountains and hills, selected Welsh districts and cantrefs documented before AD 1200, putative Anglo-Saxon/British hybrid ‘peoples’ under Mercian authority (documented from Domesday and other sources), and the kingdoms of Mercia, the Hwicce, Brycheiniog, Ergyng, Gwent and Glwysyng.

The overall length of the Dyke that is clearly upstanding and closely traceable today therefore extends across some 90 miles (c.145 km).11 Given that there are repeated characteristics that are shared between all parts of what has been known historically as Offa’s Dyke, it remains reasonable to regard the entirety of this ‘overall length’ as having been embraced within the same scheme. The locational regularities include particular stances taken up as the Dyke traverses slopes or makes its way around the (mostly western sides of) localised summits of hills; and a series of distinctive ways in which the earthwork approaches and crosses river-valleys.12 The characteristic build features that are visible in the field include the counter-scarp bank noted already, but more especially front-facing enhancements of the bank including some form of stone facing and the exposure of natural rock-faces; and the construction of lengths in series of segments arranged in distinctive ways.13 Several of these repeated locational and build features are particular to Offa’s Dyke, differing from those of other known linear earthen dykes, including the presumed near-contemporary and partly-parallel Wat’s Dyke.

Although the largely continuous upstanding earthwork that extends southwards between Treuddyn and the river Severn near Welshpool spans around 29 miles (c.47 km), its survival varies throughout that distance. It is most clearly damaged or absent where mines, quarries, housing and industrial developments have either masked or removed it altogether, or roads have been built along its bank or ditch. The areas most strongly affected by such historically recent activity are near Rhosllanerchrugog north of Ruabon and Wynnstay Colliery south of it, and at Brymbo north-east of Wrexham. In addition, Llynclys Quarry south-west of Oswestry has cumulatively removed a substantial length, and, on a much smaller scale, the construction of a lake in a landscape park in the eighteenth century at Chirk Castle has resulted in the unusual circumstance of the submergence of 200 m of its course, with the bank surviving underwater but still visible (esp...