![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Beginning Again

Where does a project begin, and how can it be said to conclude? The research described here had several false starts and at least as many false endings. So far they have spanned roughly thirty years.

So much depends on the language archaeologists use. Some time ago I offered an analysis of ‘prehistoric hoards and votive deposits’ (Bradley 1998[1990]), but all these terms give problems. The category of ‘hoard’ was considered as if its modern usage reflected some reality in the ancient world. In fact it applied to different phenomena at different times in the past. The idea of a ‘votive deposit’ fared little better, for in most cases it was treated as a residual category made up of collections of objects whose composition resisted a practical interpretation. Even the adjective ‘prehistoric’ was confusing. Over large parts of Europe it was synonymous with the pre-Roman period, but beyond the Imperial frontier it had another connotation, so that in Northern Europe it extended until the end of the Viking Age. Those problems are still with us today. Not only are similar phenomena studied by scholars working in separate traditions, there can be institutional barriers to communication between them. The period studied in The Passage of Arms was too short (Bradley 1998[1990]). Roman practices were quoted as a source of influence on indigenous communities, but nothing was said about developments in the 1st millennium AD when the archaeological record poses the same problems as it does during earlier phases.

I tried to compensate for some of these shortcomings in later publications, but always in discussing a more general theme. Thus one of the chapters in An Archaeology of Natural Places considered deposits of artefacts and animal bones in terms of where they were found. In the case of hoards it even proposed an amendment to the conventional view (Bradley 2000, chapter 4). Was it possible that certain kinds of places required particular kinds of offering, so that the relationship between the types of artefacts deposited and the character of the site should be the object of study? Topography and typology needed to be brought together.

Another amendment to my earlier account was to emphasise the life histories of individual objects and the ways in which they were treated before they entered the archaeological record. The Past in Prehistoric Societies did not say enough about the biographies of artefacts and the ways of studying them, for its main concern was with monumental architecture (Bradley 2002). Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe took an equally cautious approach, although it ventured a little further by considering the roles of incomplete objects in the Bronze Age (Bradley 2005). In particular, it argued that certain parts of broken artefacts were deposited at the expense of others (Bradley 2005, chapter 5). The idea was not taken any further as the aim of that study was to show that many of the practical activities undertaken in ancient Europe were characterised by rituals. Metalworking was only one of them.

Perhaps it is time to begin again, but on a broader chronological and geographical scale. The book has two main aims. The first is to move this kind of archaeology away from the minute study of ancient objects to a more ambitious analysis of ancient places and landscapes. It aims to break down the conventional division of labour between those who study artefacts in the museum or laboratory, and archaeologists who investigate landscapes on the ground. The second is to recognise that the problems considered in successive editions of The Passage of Arms were not restricted to the period between the Neolithic and the Iron Age. Mesolithic finds have a place in this discussion, but, more important, so do those of the 1st millennium AD. Every phase has its own literature, and archaeologists who study individual phases are confronted with similar problems although they may not be aware of it. As a result the same debates are repeated within separate groups of scholars. That is worrying enough, but it is still more troubling that they arrive at different conclusions from one another. What is needed is a review that brings these discussions together and extends across the entire sequence. If it lacks the fine detail that specialists have mastered, it suggests an approach that should apply to much of their material. Archaeologists often complain that they lack sufficient information to offer persuasive interpretations of the past. Sometimes this is true, but here is a case in which they have too much material at their disposal and not enough ideas with which to address it.

There are two ways of investigating such a complex subject. The first would be a comprehensive study of all the available material, spread over different countries and written by a team of researchers. At the moment this seems to be the preferred model for academic research, but it is an approach which is most appropriate in the sciences. The alternative is a single-author study which makes no attempt at completeness and places more emphasis on the ideas that have directed research in this field. It would not be conceived as a synthesis, but as one contribution to a discussion that is likely to continue. For that reason it could be comparatively brief. That is the approach that I have taken here. Rather than offer a comprehensive survey of evidence that has expanded beyond anyone’s control, this is an extended essay about the strengths and weaknesses of current thinking. It also considers the possibility of approaches that can be followed in the future.

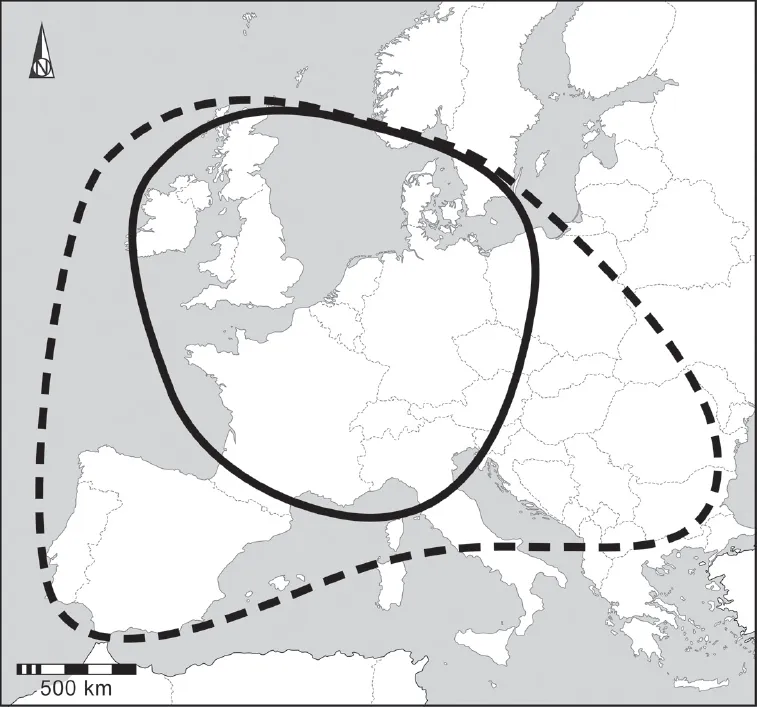

The discussion is divided into ten chapters which are mainly concerned with the archaeology of Western and Northern Europe between about 5000 BC and AD 1000 (Fig. 1). Chapter 2, ‘A chapter of accidents’ considers the main strands in the interpretation of specialised deposits and the difficulties of interpreting them in anecdotal terms. In particular, it compares the work of archaeologists studying this evidence on either side of the Roman frontier. There is much to learn from the ‘long Iron Age’ of Scandinavia, and the discussion compares the ideas that have been employed in Western Europe with thinking in Northern Europe where scholars can draw on literary sources for knowledge of pre-Christian beliefs.

That discussion continues in Chapter 3, ‘Faultlines in contemporary research’, which considers the institutional division between pre-Roman, Roman and early medieval archaeology. It compares the interpretations of specialised deposits between different researchers and different regions of Europe and asks how far the contrasts between them result from practices followed in the past and how far they reflect traditions of modern scholarship. In particular, it argues that work in this field has been influenced by one particular conception of the role of early coins and by the adoption of Christianity during the 1st millennium AD. It advocates a new approach to hoards and related collections based on the histories of individual artefacts and the places where they were deposited. It ends by suggesting that their distinctive character provides vital information on the concerns of people in the past. In taking this approach, field archaeologists can build on what has been achieved by traditional research.

Figure 1. Map showing the extent of the study area. The main regions considered are within the continuous line. The dashed line encloses areas providing additional examples.

Chapter 4 is called ‘Proportional representation’ and considers the range of specialised deposits and the way in which certain categories of material can dominate the discussion. The obvious example is metalwork. There are regions in which less attention has been paid to stone artefacts such as axeheads, or to wooden objects, food remains and pottery. Is it because the character of these collections changed, or does it reflect the division of labour between different groups of specialists in the present? It comments on the relationships between two different strands in prehistoric archaeology: sacrificial deposits characterised by large quantities of animal and human bones; and other collections which are dominated by finds of stone or metal artefacts. For some time they ran in parallel or overlapped, and this account traces their histories from the Mesolithic period to the Viking Age.

Chapter 5, ‘The hoard as a still life’, begins with a comparison between hoard finds, mainly those of the Bronze Age, and the collections of valuables depicted in 17th century Dutch paintings. These pictures had two key elements. They portrayed exotic and costly objects collected during the expansion of trading networks to Asia and featured new materials such as porcelain and lacquer. At the same time they assembled these striking objects into formal compositions that offered a medium for conspicuous consumption. The chapter argues that ancient hoards had some of the same properties; this interpretation is suggested by prehistoric rock art. The discussion also draws on the archaeology of the 1st millennium AD to suggest that the artefacts recorded as hoards and single finds may be all that survive of public displays of special objects taken out of circulation as their use lives came to an end.

Chapter 6, ‘The nature of things’, explores the character of the material found in these collections. It considers some of their properties that have been overlooked in the past: properties that extend well beyond their mechanical performance. In particular it investigates the distinctive character of worked stone and metalwork, drawing on new analyses of important artefacts. Ethnographic sources shed even more light on their original significance. Then Chapter 7 takes the discussion further by asking how different elements were treated as they entered the archaeological record. Why were certain features selected at the expense of others, and how did that choice determine the condition in which they are found today? For example, some stone artefacts were re-sharpened before they were discarded, but others were destroyed. The same applies to later finds of weapons. This account also draws attention to the anomalous position of the smith in ancient society and the peculiar practice of depositing incomplete objects.

Chapter 8, ‘Vanishing points’, discusses the reasons why deposition took place. Drawing on literary texts, it reviews current interpretations, from conspicuous consumption to sacrifice. It also considers the dangers posed by objects with special attributes or associations and the risk that their powers would be dissipated if they were treated as private wealth. That could have been one reason why they were removed from circulation. Finally, it emphasises the importance of gift-giving and suggests, as others have done, that this practice extended to dealings between people and the supernatural.

Chapter 9, ‘A guide to strange places’, considers the topographical setting of special deposits. Although there are notable exceptions, it contends that most scholars have treated the subject too casually. In particular, they have attempted to define specialised offerings according to practical considerations. Where material was buried and could be recovered, it might have been hidden in the ground. No doubt there were times when that did happen, but where it really was inaccessible – in a rock fissure, for example, a river or a lake – a different interpretation was required. The problem is that this approach said little about the character of the places where these artefacts were discarded. Water was not just a medium from which they would be difficult to retrieve; it had distinctive properties of its own. The same applies to dry land, for the character of the findspots is equally idiosyncratic. This chapter compares the evidence from Northern and Southern Europe and tries to identify those elements.

Finally Chapter 10, ‘Thresholds and transitions’, brings these observations together and proposes some new ways of studying the ancient landscape. It explores the importance of animism and the character of ancient cosmologies. The basic conclusion is simple. Hoards and related deposits have been studied for over a hundred years and analyses of their contents are rapidly approaching exhaustion. At a time when they have achieved many of their original aims, it is worth asking whether their results can be deployed in a different way. It suggests that this can be achieved by developing a ‘geography of offerings’. In that case some of the most traditional studies can play a new role in a more ambitious approach to the past.

Why is a change of emphasis needed now? Over the last 20 years the development of metal detectors has transformed the character of archaeology. In some parts of Europe it is subject to few limitations; in others, it is more or less illegal. There are cases in which their use makes a direct contribution to fieldwork. This is especially true in Northern Europe, but provisions for recording the finds made on unprotected sites differ from one country to another. Even where progress has been made, as it has with the Portable Antiquities Scheme in England and Wales, metal detecting has serious consequences for the character of research. Although there have been worthwhile studies that use this source of information (Naylor & Bland 2011), it can easily encourage a new antiquarianism, concerned with the minute analysis of ancient artefacts at the expense of their wider significance.

In short it is essential to put this material to better use. There are many ways of achieving it, but here the premise is straightforward. It is to treat the deposition of distinctive artefacts and their associations as evidence of the cognitive geographies of people who left little else behind. That is why this material is still important and why it provides the point of departure for this book.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

A Chapter of Accidents

This account begins with four notable discoveries, separated from one another by time and space. They share the common feature that these finds were first interpreted in practical terms and have since been reassessed.

The Broadward hoard

Discovery and initial interpretation

In 1867 a large deposit of metalwork was discovered near the border between England and Wales. The Broadward hoard dates from the end of the Bronze Age and is associated with radiocarbon dates between 980 and 820 BC (Bradley et al. 2015). It is composed almost entirely of weapons. Not all this material survives, yet even today the finds in the British Museum account for about 50 spearheads, five ferrules, two swords, a chisel and a chape. Many of the artefacts were broken and were in a single deposit interpreted as the stock of a smith.

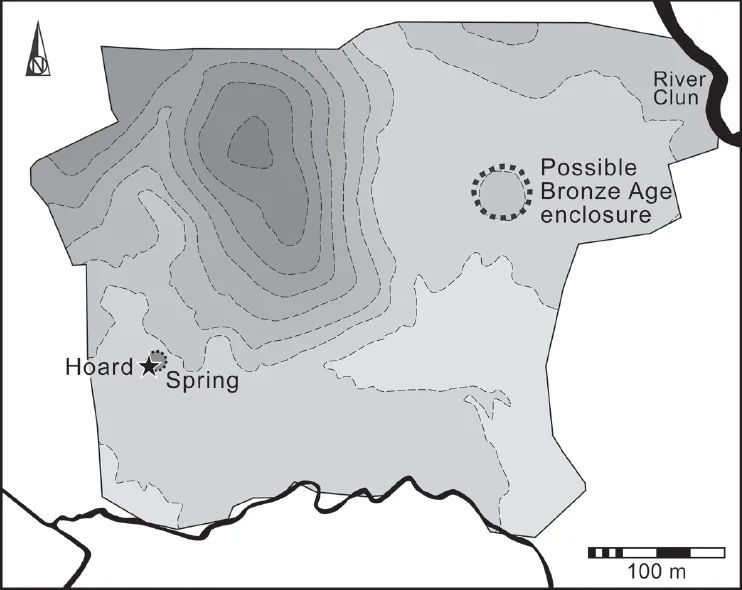

The artefacts were found in digging a well on the edge of a poorly drained fen beside a tributary of the River Clun (Fig. 2). The hoard was located at the junction between the wetland and an area of dry ground:

‘[It was] at the extreme edge of the swampy ground, where it rises abruptly to a higher level. [The findspot was] on the very edge of [a] former morass … Spear-heads and fragments of various patterns lay in a confused heap … Many were taken from the earth cemented together with the gravel into large lumps, the points laying in all directions’ (Rock & Barnwell 1872, 344).

Figure 2. Outline plan of the Broadward complex showing the spring where the Late Bronze Age hoard was found and the position of a circular enclosure apparently of similar date. The two locations cannot be seen from one another and are separated by an area of higher ground. Information from Bradley et al. (2015).

One account records that these artefacts were associated with ‘large teeth … chiefly of a small equine species’ (Barnwell 1873, 80). Another report went further and offered an explanation for the finds: ‘Whole skulls of ox and horse … were taken up with the spears and other bones of the animals, as if beasts of burden and their freight had been swamped in the bog’ (Rock & Barnwell 1872, 343).

The Mästermyr hoard

Discovery and initial interpretation

A similar interpretation was suggested for a hoard from Gotland where, in 1936, a wooden chest was discovered at Mästermyr. It dated from the late 10th century AD and was associated with entire or fragmentary cauldrons, anvils, tongs, and a variety of tools (Arwidsson & Berg 1983). Other kinds of object were represented by single examples and were for preparing food, wood working and iron production. There were also whetstones and a piece of unworked brass. Again these items were interpreted as the property of a smith. More puzzling was the presence of three bells.

If that was difficult to explain, there seemed no problem in deciding how the deposit had formed. It was discovered on the edge of a bog, and pollen analysis suggested that the local environment had been similar when the artefacts arrived there. According to the definitive account of this find:

‘It is generally accepted that the chest – which was presumably too heavy to carry – and the objects found near it were lost while crossing an ancient waterway, that it fell from a capsized boat or perhaps from some vehicle travelling on the ice’ (Arwidsson & Berg 1983, 6).

This idea is remarkably like an interpretation of the Broadward hoard. The coincidence is striki...