![]()

Chapter 1

Past dark: a short introduction to the human relationship with darkness over time

Robert Hensey

‘To Know the Dark’ – Wendell Berry

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is travelled by dark feet and dark wings.

Darkness within darkness

Though comprehensive books have been penned on areas related to darkness, such as the history of the night and the increasing electrification of the world (Bowers 1998; Jonnes 2003; Dewdey 2004; Ekirch 2006; Koslofsky 2011; Bogard 2013), literature on the subject of darkness from an archaeological or historical perspective – especially as regards human interactions with ancient places and monuments – is rare, if not nonexistent. Given that darkness would have had an even greater role in the past than it has today, it is unclear why this might be so.

One possible explanation is that darkness has been so much part of our lives and of the history of our species that we tend not to acknowledge it; it is too big to see, too fundamental, too pervasive. Darkness is so many things: the dark of night; the darkness of deep winter; the darkness of the subterranean world; darkness as a metaphor we live by. It is only recently as we have been able to exclude it more successfully from our lives that, conversely, we have become more aware of it, realized we may be missing something.

Another reason perhaps is that darkness, by its very nature, seems to repel objectification – to actively resist study. You cannot photograph the dark, for instance. When we see images of deep caves or megalithic recesses we can only do so because of camera flashes and other artificial means of lighting. What we are actually photographing is the temporary removal of darkness. Darkness is the opposite of ‘illumination’, enlightenment – and all those other light-oriented words we rely on so heavily to describe understanding (Thomas 2009); the dark is where the unseen, unformed and misunderstood things abide, that which has not been examined in the cold hard light of day. The route to ‘understanding’ the dark may be somewhat different than other areas of investigation. Wendell Berry’s poem ‘To Know the Dark’ at the beginning of this piece captures something of this elusiveness.

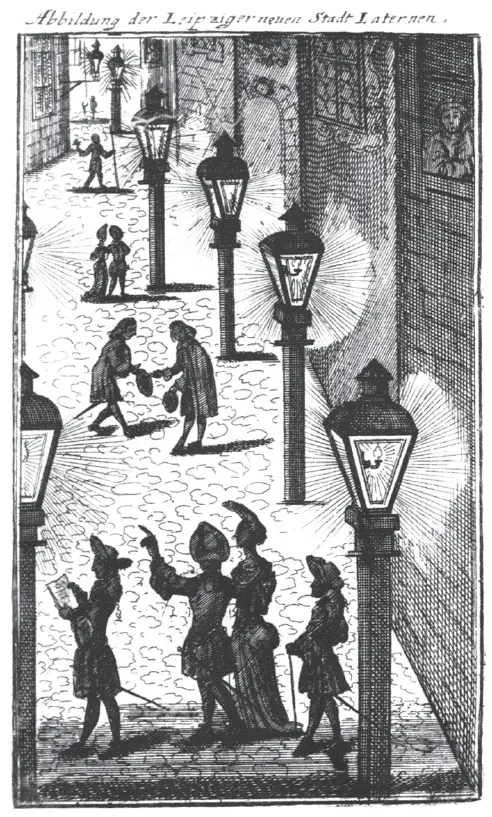

A further factor that could explain our limited appreciation of darkness is that we may have simply lost touch with it over succeeding generations. For three hundred years we have gradually been lighting up our world, particularly over much of the last century. It is now estimated that two thirds of Europeans and Americans no longer experience real night or darkness (Bogard 2013, 9). In Evening’s empire: a history of the night in early modern Europe (2011), Craig Koslofsky records perceptions of light and dark in European history over the course of our steady ‘colonization’ of the night. He details the dramatic change in the lives of European city inhabitants that came with the introduction of street lighting from the eighteenth century onwards, in particular the pacifying effect light had on cities (Fig. 1.1). People began to see the night in a more positive way; it was now safe to go out in the night, deviant behaviours had less places to hide – the threat of darkness was being driven back. This process of driving out the dark has continued to a point whereby we now have almost complete ability to exclude darkness from our everyday lives. Indeed, as Bogard (2013) has highlighted in The end of night: searching for natural darkness in an age of artificial light, it has become difficult to find places in our world where we can see truly dark skies anymore.

Perhaps it is because of the naturalization and ever-presence of artificial mediums of light that darkness today can hold a certain fascination for us; it has become a novelty. Charitable road race events such as Run in the Dark and Darkness into Light have become innovative mediums for fundraising. ‘Dancing in the dark’ events have become popular. Restaurants in major cities all over the world now offer ‘dining in the dark’ experiences. Some are exclusively dark dining venues. The first of these was opened by a blind man in Zurich, Switzerland in 1999 (Dewdney 2004). He employed only blind table staff to serve diners and guide them around the restaurant, giving his customers an insight into the sightless world. One reason ‘dark dining’ has taken off is because diners say that with restricted sight their other senses become more heightened. One’s sense of taste and smell of course is magnified, but the texture of foods becomes a more important part of the eating experience too, as does consistency and temperature. This increase in sensory experience perhaps runs counter to the sensory deprivation that we might at first tend to associate with darkness – and is something that perhaps should be considered as we interpret human engagement with dark sites and monuments in the past.

Figure 1.1: Leipzig street-lighting scene, 1702 (print adapted by Cambridge University Press, with permission, from the journal Aufgefangene Brieffe (1701) for Koslofsky 2011, fig. 5.4).

Darkness and archaeology

The role of darkness is hugely apparent in the archaeological record. Many artefacts were intentionally deposited in places that exclude light, not only caves and megalithic monuments, but also barrows, cists, pits, tree throw holes and countless other site types, or simply buried directly into the earth. Moreover, while there are certain activities we automatically think of when we consider the past – tool production, food procurement and building – other necessary activities would have taken place in the subterranean world, such as mining for stone tools and metals (e.g. Russell 2000; James this volume). Vast subterranean quarries such as Grimes Graves indicate just how much time was spent in shadowy underground tunnels sourcing materials for upperworld activities (Mercer 1981).

Our tendency is to view archaeological monuments and sites only in the bright light of day. Artificial light has an important role in archaeology too. We examine megalithic chambers with powerful torches, aiming to expose corners and niches, to reveal all in precise and measurable detail. But perhaps in doing this, by driving out shadow, we miss part of the story of these places. Is it possible that in some cases darkness was not an incidental feature of a site or place but a fundamental feature (also see Pettit this volume)? Illuminating these sites and monuments, removing artefacts from their repositories, may result in excluding a crucial foundation of the ritual that lay behind the deposition: darkness.

Chris Tilley (2008, 117), for instance, has noted that our exacting recording of megalithic art, laying bare every incision and peck mark, betrays the actual experience of entering a decorated monument where many motifs were intended to be more hidden, perhaps shrouded in darkness, whereas other designs were intended to be visible. A person in the Neolithic, not having the advantage of the catalogue of motifs we have today, would have missed many of the less prominent or badly lit carvings. Conversely, the size and/or prominent position within the monument of other designs may have meant those examples loomed larger and perhaps struck people more forcibly, leaving a more lasting impression. When we remove darkness from the equation, we remove something of the experience of place.

As noted already, most of what we investigate in archaeology has to do with people’s outward activities. Because of this we rarely consider people’s inward life or emotions and how that might impact on the archaeological record (Tarlow 2000). For instance, one of the persistent associations with darkness is fear. One imagines fear of darkness is very deep within our species, perhaps rooted in us at a genetic level. For so much of our evolution, a poisonous creature or a human assailant lurking in the dark could have meant injury or death. It is then somewhat understandable that fear of the dark, achluophobia, is suffered by children and adults alike. Fear of darkness is reflected in much folklore, mythology and religion (Ekirch 2006). In Christianity, Lucifer, the angel of light, transforms into Satan, the ultimate symbol of fear, the prince of darkness (Koslofsky 2011, chapter 2).

The dead, and various lands of the dead such as the Greek Hades, are also associated with darkness and night. Of course these places too are often associated with caves, swallow holes, and other entrances into the earth or the ‘underworld’ (Davies and Robb 2004). Most living things, in particular vegetation, stop at these thresholds. Connections with life and death lend darkness a theatrical power which may have been harnessed in past myth. Yet darkness can equally be protective and nourishing; the dark safe womb; the life-giving earth where seeds germinate and from whence life springs forth.

When we speak about darkness we need to be aware that there are different types or levels, or that different people may associate darkness with differing levels of visibility. For instance, there are places and monuments which seem internally very dark on first appearances but as one’s eyes become accustomed, especially if prolonged time is spent inside, one realizes that actually quite a lot can be seen. To discuss this subject we may need to reclaim knowledge of, and language for, different types of darkness. It may be better not just to speak about ‘darkness’, but about ‘opaque’, ‘crepuscular’, ‘sunless’, ‘inky’, ‘pitch-black’ and other types and degrees of darkness. Terms such as these could be associated with a simple scale describing degrees of darkness in a not dissimilar way to how we use the Munsell colour chart to describe soils in archaeological excavation. Though we do not as yet have a technical scale for the degrees of darkness of the interiors of archaeological sites, one does exist to measure the darkness of the night sky. This scale, created by John Bortle in 2001, ranks the night sky from 9 to 1, from the heavily obscured inner-city skies that many of us experience today (9), to ‘truly dark’ locations (1) a quality of darkness that most of us have never experienced (Bogard 2013).

Newgrange is a place that we naturally tend to think of in terms of extreme light and dark, the visitation of the rays of sun on the winter solstice at the very darkest point of the year. Crowds of people visit Newgrange every December, and it is probable that the passage tomb complex was a place of gatherings in the Neolithic also (Hensey 2015). Pilgrimage is not something that we automatically associate with darkness – though those familiar with the pilgrimage site of Croagh Patrick in Co. Mayo will know that people traditionally climbed the mountain at night. It is possible that some people travelled at night to Newgrange, even if only from nearby settlements, to reach the site before sunlight entered the monument at dawn. However, due to the limited size of the chamber, very few people would actually have been able to enter the structure to witness the entry of light; most probably gathered outside the monument before dawn and waited in darkness. One could say that darkness was a key component of the winter solstice Newgrange event (and other astronomically oriented sites), yet that aspect is rarely considered.

Outer darkness and inner light

Very elderly Irish people still talk with great enthusiasm about the Rural Electrification Scheme of the 1950s and the many benefits it brought to their lives; though the philosopher and writer John Moriarty (1998) has spoken about the subtle loss of perception people experienced with this change. Yet even with considerable electrification of our lives, we spend much of our time in darkness. Sleep takes place in darkness, as do dreams. People in the past must have wondered where dreams came from, or at the connections between darkness and inner vision. In Irish folktales, night and darkness are associated with spirits, danger, and potentiality, and are sometimes a symbol for dramatic changes of fortune (Danaher 1972; 1988).

Absolute darkness could be described as the visual equivalent of silence. Records of diverse cultures in which periods of silent retreat in darkened places were undertaken are common. In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition retreats in total darkness (typically for 49 days) have been part of religious practices at least since the fifteenth century. They were known as Yangti nagpo, or Single Golden Syllable of the Black Quintessence (Ricard and Shabkar 1994, note 17). A famous female retreatant from that tradition, Ayu Khandro Dorje Pendron, born in the mid-nineteenth century, is reputed to have spent many years in dark retreat (Tsultrim 2000, 71). A visitor to her retreat house records that even in old age she could see much better in the dark than he, and she did not need the candles which he required (Norbu 1986, 146). In this religious context, one of the reasons for the dark environment was to better achieve the mental visualizations necessary to a particular meditation practice without outward visual distraction. Equally, in Christian hagiography, several saints were believed to have spent time in caves and similar retreat places pursuing spiritual goals. In this they were following the lead of the ascetics of the deserts of Syria and Egypt (Chryssavgis 2009). For willing retreatants such as these, darkness in isolation could be seen as a unique opportunity where high levels of tranquillity might be found, or perhaps where temptations could be overcome and saintly qualities developed.

Yet it would be wrong to think of solitary isolation in darkness as simply a pleasurable pursuit or a spiritual indulgence of some kind. It is notable that solitary confinement and deprivation of natural light are two of the most severe forms of punishment that have been meted out in prison systems throughout the world. Unquestionably time spent in isolation and in darkness could be a challenging ordeal and was not something for the faint-hearted. Brian Keenan’s (1991) disturbing account of nine months in total darkness, the beginning of a four-year period as a hostage at the hands of Islamic Jihad, is testament to how challenging this could be.

A site famed for its fear-filled journey into darkness is the cave-like structure known as St. Patrick’s purgatory which once existed on one of the pilgrimage islands at Lough Derg, Co. Donegal (Dowd 2015). The fame of this pilgrimage site spread all over Europe in the late medieval period (Fig. 1.2). It was thought to be an entry point into purgatory, a place where one could pass through the tortures awaiting one after death, whilst still in this life, and thereafter be granted heavenly visions. We know, for example, of an Italian merchant and pilgrim named Antonio Mannini who left his home at Florence, eventually ending up at St. Patrick’s purgatory...