- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prehistoric Britain

About this book

Pottery has become one of the major categories of artifact that is used in reconstructing the lives and habits of prehistoric people. In these 14 papers, members of the Prehistoric Ceramics Research Group discuss the many ways in which pottery is used to study chronology, behavioral changes, interrelationships between people and between people and their environment, technology and production, exchange, settlement organization, cultural expression, style and symbolism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

Ann Woodward and J. D. Hill

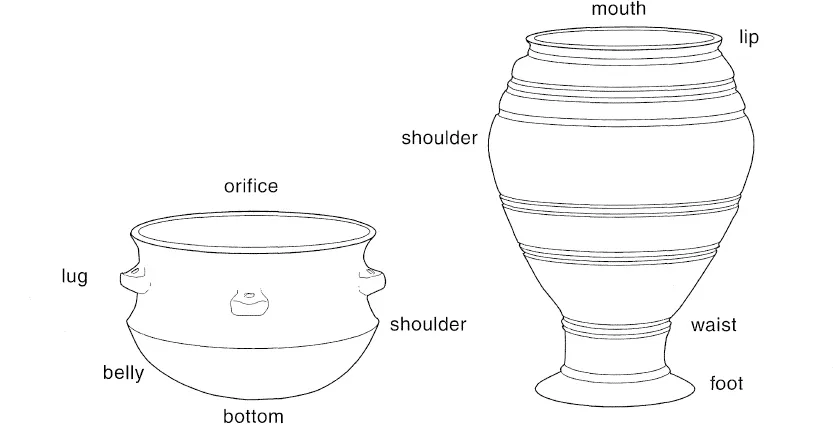

Pots are very closely related to people. Across the world, the terms applied to different parts of baked clay vessels are derived from descriptions of parts of the human body (Fig. 1.1). Nigel Barley has stated that Tots lend themselves to thinking about the human form' and observes that in West Africa this rich imagery recurs as a major cultural theme (Barley 1994, 85). But we need to ask why this should be so. One possible answer is that in many societies, both ancient and modern, it is pots that form the vehicle whereby two of the essential requirements of human life – food and water – are introduced into the human body itself. The other crucial human requirement is heat and warmth, and it is this property that is engaged to make the pots in the first place. The transformation of clay, part of the living earth, by fire, creates an entirely novel and man-made material – a medium which is both malleable, plastic and highly versatile becomes, when fired, a hard, rigid and highly fragile category of material culture. However the theme can be developed even further, because it is through the application of heat to the finished pots that liquids may be heated, and foodstuffs cooked. So, the beverage passes from the lip and mouth of the cup to the human lips and mouth, and warm food from the belly of the jar enters the human stomach.

This fundamental and close connection between pottery vessels and the human body suggests that pottery might be a powerful indicator for many of the things that we wish to know about people in prehistory. For instance, we need to investigate how people lived, worked and subsisted on a daily basis, how their activities varied by the seasons, how they celebrated festivals and rites of passage at home and with other people, how they interrelated and socialised with their neighbours at local and regional levels, and how they related to the world around them. We believe that the enlightened study of pots can go a long way to inform many of these lines of enquiry. This is partly due to the close corporeal symbolism outlined above, but also to some key aspects of ceramic technology and usage.

Firstly, fragments of pottery survive well in the soil. Amongst the wide-ranging categories of raw material used during prehistory – metals, bone and antler, flint and stone, fur, leather, reeds/withies, wood and bark, lithic items are the only artefacts that survive as well as potsherds. Therefore there are substantial quantities of pottery to be discovered and studied. Secondly, due to its exceptional plastic qualities, clay can be crafted in a multitude of ways – it is conducive to the production of vessels of widely ranging size, shape and style which may be adorned with surface treatments and decoration executed in myriad techniques. The subtle changes of these parameters through time and space mean that pottery provides a powerful tool for the analysis of chronological change and for the study of changing style within individual homesteads and larger settlements, as well as across neighbourhoods and regions. Thirdly, clay pots form versatile and convenient containers. Whilst baked clay was used for other purposes, notably for ovens, hearths, walling, whorls and perforated weights and (though not in Britain) to mould anthropomorphic or animal figurines, its prime usage appears to have been in the production of vessels.

Fig. 1.1. Pots as bodies.

This brings us back to our first topic, as vessels were involved primarily with the manipulation of food and drink. The multifarious functions of pottery in this realm can be divided into three main areas of activity: storage of commodities, heating and cooking, and finally, the presentation and serving of foodstuffs and beverages. The invention and adoption of pot making and a more home-based existence (Ian Hodder's domus – 1990a) from the Neolithic onwards allowed the art of cooking to be developed in far-reaching and exciting ways. Previously many wild plant foods would have been consumed in a raw state, as may some animal products, although there is evidence for the roasting of meat, and some may have been boiled in animal skin containers. However, clay pots immediately allowed the opportunities to cook food in many more ways: boiling, simmering and stewing probably were the mainstays of the possible new techniques, but the methods of poaching, frying and steaming no doubt also were employed. Prehistoric societies were able to enter new realms of food preparation – truly a prototypical nouvelle cuisine. At the same time the potential to manufacture vessels of many different sizes, shapes and styles meant that customs of presenting food, drink and drugs, both at the domestic and communal levels could be elaborated to a high degree. The shapes, colour, texture and decoration of pottery vessels could be developed to signify kinship or status, and to act as symbolic markers relating to many spheres of social and spiritual life. These are the sorts of connections that this book is intended to address.

Fig. 1.2. Gussage All Saints: distribution of imported ceramics in the Late Iron Age phase (after Hill 1995a, Fig 9.21).

The Prehistoric Ceramics Research Group is an independent body of about a hundred ceramic specialists who meet biennially to discuss aspects of prehistoric pottery in England. We do two main things: the handling and viewing of large, usually newly discovered, assemblages of prehistoric pottery around the regions, and the discussion of theoretical and practical approaches to the study of such pottery. Initially, the Group confined its scope to pottery of Iron Age date, but in recent years coverage has been extended to include Neolithic and Bronze Age pottery also. In 1991, the Group produced its first Occasional Paper which comprised a brief presentation of a set of general policies, and this was followed in 1992 by the Guidelines for Analysis and Publication. These related to pottery of Late Bronze Age and Iron Age date only, but such has been the demand, that they have been reprinted in 1995 and 1997. The General Policies define a set of seven academic issues for consideration. These are deposition, chronology, manufacture and technology, production and exchange, function, settlement organisation and cultural expression.

It is these issues that provide the format for the first section of this book. However, since the formulation of the seven issues in 1991, much has happened, both within pottery studies and in the study of British prehistory in general. The divisions between such definite themes have become blurred, and certain more wide-ranging and far-reaching goals are being attempted. Such goals include in particular the analysis of structured deposition in features and on sites of all kinds (Fig. 1.2) and the interpretation of style, colour and decoration in relation to social and cultural expression. The inevitable result of all this is that the reader will be able to detect a considerable degree of overlap between the content of several of the papers in the first section of the book.

Also, in the second section, which includes a series of detailed case studies, the themes of style and symbolic function will be seen to loom large. However plenty of hard facts and practical information will also be found. The case studies vary from a detailed regional study of later prehistoric ceramics in the East Midlands, intended to counter the common concentration on the better known sequences of southern England, through studies of form and function in varying periods (the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age of the Thames Valley, Beaker pottery, the later Iron Age of East Anglia and the theme of Roman pottery found in Iron Age Britain) to a more general consideration of the potentially symbolic significance of decorative techniques and motifs from the Neolithic to the Early Iron Age periods. Most of the papers have been contributed by past or present officers and committee members of the Group.

We are extremely grateful to all our contributors, who worked cooperatively within the confines of the original design set for the volume. Many of the papers were submitted in 1996 and 1997, but a few were not completed until 1999 or 2000. minor updating has been undertaken in 2002. For this reason most papers do not contain references to publications appearing after 1997. We also thank the University of Southampton, The British Museum and Robert Read for assistance in the preparation of the illustrations. Many people have acted as academic readers. These included Niall Sharpies, Elaine Morris, Steven Willis, Bill Sillar, Colin Haselgrove and Sue Hamilton. We would also like to thank The Prehistoric Society, The University of Oxford Committee for Archaeology, Oxbow Books, Wessex Archaeology and many individual authors for permission to use or redraw many of the illustrations in the volume. Our aim has been to produce a book about pottery which is primarily about people, not pots, and which is illustrated not by drawings of pots, but by diagrams, plans and drawings which show why pottery is of paramount importance to prehistorians, both in Britain and around the world.

2 A Date with the Past: Late Bronze and Iron Age Pottery and Chronology

Steven Willis

"The identification, recovery and detailed analysis of sufficiently diagnostic groups in stratigraphic sequences is of fundamental importance ... In view of the problems with Carbon 14 calibration there is a need for greater use of other scientific dating methods to provide an absolute timescale ... Secure associations, particularly with dateable imports and metalwork, remain important" (PCRG1991,4).

Introduction

The chronological framework for much of Britain during the first millennium BC is still largely reliant upon pottery remains (cf. Barrett 1980, 297). This paper examines a range of issues relating to the dating of later prehistoric pottery and the use of this pottery as dating evidence. It does not attempt to present a purely chronology centred perspective nor an all-encompassing survey of the development of later prehistoric pottery chronology over the past century. Rather the aim is to offer a review of the 'state of the art' and to set this within the context of later prehistoric studies. In the first sections of the paper the importance of dating for later prehistory, and its inherent difficulties, are set out. This is followed by assessments of the various means by which we are able to sequence and date this key material. The focus of the later sections is upon substantive problems and themes and explores how later prehistoric pottery chronology relates to the wider aspects of the period. I have endeavoured to make this a relevant discussion for those already working in first millennium BC studies, but also an accessible essay for readers who are non-specialists or new to this field.

Though never out of fashion, dating has rarely been as central a theme in Britain as it has in later prehistoric research on the continent. This fact must explain why, surprisingly, there has been no specific synthetic literature dealing with the dating of later prehistoric pottery in Britain in recent years. Examination of the dating of Late Bronze Age and Iron Age pottery and related issues is timely since this has recently excited heightened attention for various reasons. Not least amongst these are recent initiatives such as the luminescence dating research project being conducted at Durham University by Sarah Barnett and the English Heritage Later Prehistoric Pottery Register co-ordinated by Elaine Morris, the collated results of which will surely provide some totally new perspectives on the chronological distributions of this material. Further, the dating of the Late Iron Age and its pottery in Britain and in northern France and Belgium has received special attention during recent years.

Why is Dating Important?

To address this question it may be of value to begin by reflecting upon the fundamental contrast between the vast existing temporal knowledge of our contemporary world and its recent past and the limited framework that we operate within when approaching later prehistory. Considering our own Western culture, its astonishingly well documented and accessible record of historical dates and series of events is a defining characteristic, and the utility of being able to locate or place an object or event within a temporal sequence is readily apparent. The temporal reference points, temporal structures and temporal data of our culture form an immensely rich chronological milieu by means of which we make sense of the world and which we draw upon in order to deepen our awareness of both it and of human being.1 An absence or limitation of temporal information restricts our potential to understand and interpret the past. First millennium BC studies, by contrast, operate within a framework of restricted chronological information and certainty, and hence require particular approaches.

Establishing chronological frameworks is a fundamental aspect of the archaeological project. Archaeological 'dates' and chronologies constitute our attempts to impose form upon the otherwise temporally undifferentiated past in order to make it interpretable (cf. Simmel 1971, 353–431). They are conceptual and methodological tools for understanding finds and 'what was happening'. Dating and the establishment of chronologies enables us to place artefacts and assemblages, and in turn sites and processes, within a temporal context. This is one of the first steps towards being able to say something meaningful about ancient evidence, facilitating ordering, comparison and assessment of rates of change. The quality of our dating frameworks imposes itself upon the type of archaeology we can construct on the basis of it. In other words the degree to which we are able to place material (in this case pottery groups) within a reliable sequence, and in particular the tightness of the date brackets we can assign it, has deep implications for what we can then use this material and information for. Moreover, since 'the date' of recovered pottery may well be the principal dating evidence available for an excavated context, site phase, or, indeed, a site as a whole, the same constraint applies to the use of these tiers of evidence as well: if pottery dating is vague so too may be the dating of sites. Our current ability to date material and sites within the first millennium BC requires improvement since it is relatively imprecise and thus limiting. Whilst this situation has not precluded expanding interest and new research into various aspects of the archaeology of the period it must hinder its scope.

To the experienced archaeological practitioner reference to the limiting nature of comparatively broad brush dating schema will be familiar. However, there are qualifications that may be made to this picture. First, the importance of dating is not fixed and absolute. Individual archaeologists will differ in perspective over how important dating, and precision in dating, may be to their archaeologies. Its importance will depend on the nature of the material (e.g. pottery) being assessed and on the sort of archaeological questions being addressed. Secondly, though little typological change in pottery over long time-periods may hinder attempts at chronological differentiation this continuity is in itself of no small interest; as has been pointed out (cf. Haselgrove 1989, 1–3), later prehistorians have tended to focus differentially upon periods of overt change, to the detriment of the study of those time-spans with seemingly little apparent change. Third, if dating frameworks are less than precise this may well affect archaeological research agendas in a way that is not negative, by leading to concentration upon different sorts of questions, such as examining long term developments, relative sequences or the study of processes and activities for which comparatively close dating may not be crucial, for example spatial analyses. In this way the character of our dating frameworks can profoundly influence what sort of archaeology the study of the British Late Bronze Age and Iron Age is and can be.

It would be a misconception to believe that an unequivocal 'black and white' chronology for the period somehow exists within the archaeological record awaiting discovery. Chronology will invariably have interpretative and contested elements. Just as Julian Thomas has observed in the case of human i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- 1. Introduction (Ann Woodward and J. D. Hill)

- 2. A Date with the Past: Late Bronze and Iron Age Pottery and Chronology (Steven Willis)

- 3. The Nature of Archaeological Deposits and Finds Assemblages (Joshua Pollard)

- 4. Aspects of Manufacture and Ceramic Technology (Alex Gibson)

- 5. Between Ritual and Routine: Interpreting British Prehistoric Pottery Production and Distribution (Sue Hamilton)

- 6. Staying Alive: The Function and Use of Prehistoric Ceramics (Elaine L. Morris)

- 7. Sherds in Space: Pottery and the Analysis of Site Organisation (Ann Woodward)

- 8. Pottery and the Expression of Society, Economy and Culture (J. D. Hill)

- 9. Ceramic Lives (Alistair Barclay)

- 10. Pots as Categories: British Beakers (Robin Boast)

- 11. Inclusions, Impressions and Interpretation (Ann Woodward)

- 12. A Regional Ceramic Sequence: Pottery of the First Millennium BC between the Humber and the Nene (David Knight)

- 13. Just About the Potter's Wheel? Using, Making and Depositing Middle and Later Iron Age Pots in East Anglia (J. D. Hill)

- 14. Roman Pottery in Iron Age Britain (Andrew Fitzpatrick and Jane Timby)

- Bibliography

- Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Prehistoric Britain by Ann Woodward, J. D. Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.