![]()

Part I

The Represented Body

![]()

1

Polydactyly in Chalcolithic Figurines from Cyprus

Michelle Gamble, Christine Winkelmann and Sherry C. Fox

Mimesis is the imitation of nature and life in art or literature. According to Plato, all art is mimetic of life and therefore a reflection of reality. This theory has spawned an entire philosophy and study of art and the nature of reality and identity (i.e. Potolsky 2006, Halliwell 2009 – for a prehistoric example see Borić 2007). If art does indeed reflect reality, then this could present a window into the past, representing either ideal images for a particular period or specific individuals. In some cases, it is possible to observe the integration of a specific biological phenomenon into artistic representation, such as personalised characteristics of an individual or a particular disease or deformity (i.e. Barnes 1994, Case et al. 2006, 222). Polydactyly is an epigenetic malformation affecting the hands or feet with one or more extra digits. This paper aims to explore the expression of polydactyly in Chalcolithic Cypriot art by documenting the variations in the number and location of the digits presented in the figurines from this period. It will further discuss some of the possible interpretations of these figurines, with regard to the significance attached to polydactyly, through ethnographic examples and an examination of figurine studies on the island.

The Chalcolithic period on Cyprus (c. 4000/3900–2500/2400 BC from Knapp 2013, 27) was a dynamic time of increasing social complexity and hierarchy where art flourished. Figurines of hard stone, the mineral commonly referred to as picrolite and clay were rendered by artists on the island, and in all materials, figurines with extra fingers and/or toes have been identified. As art can imitate reality, representations of polydactyly on figurines dating to the Chalcolithic period from Cyprus may demonstrate the condition amongst early Cypriots.

Definition of polydactyly

There are several types of polydactyly, classified by their location on the extremity and the nature of the extra digit. The supernumerary digit can take a range of forms from a small mass of soft tissue (with no osseous changes) to a fully developed extra digit including an extra metatarsal or metacarpal and phalanges. They are typically associated with the 1st (preaxial) or 5th (postaxial) ray of the hands or feet, with the postaxial variety the more common of the two (Temtamy and McKusick 1978, Case et al. 2006, 221–2). The heritability of the supernumerary digit is dependent on the type of polydactyly and environmental factors with a range of degrees possible. “Pedigree studies of polydactyly tend to attribute inheritance of most forms to a dominant gene with variable expressivity” (Holt 1975, Case et al. 2006, 226). With unpredictability in the expression of polydactyly, even amongst close relatives, it becomes difficult to use this anomaly to explore familial relationships in the osteoarchaeological record, particularly as some forms of polydactyly do not include osseous changes. However, within a bounded context, such as a tomb group, multiple examples of the expression of a heritable trait can suggest biological relatedness (Wrobel et al. 2012, 134).

Polydactyly was observed amongst living Cypriots by J. Lawrence Angel in 1972, and thus could be a trait with some longevity on the island. Angel recorded polydactyly amongst 20th century Turkish Cypriots from the village of Episkopi in the Limassol District. He failed, however, to include whether extra toes or fingers were present and the type of polydactyly (Angel 1972). Modern examples of the deformity are more difficult to learn about as they are frequently dealt with surgically and are currently not recorded in the health statistics of Cyprus.1 There is great disparity in the locations and time periods where polydactyly is represented (i.e. Klaassen et al. 2012). It is an abnormality which can be observed in any population to a greater or lesser extent (for studies regarding the prevalence of polydactyly, see, for example, Bingle and Niswander 1975, Temtamy 1979, Al-Qattan 2010, Belthur et al. 2011, Materna-Kiryluk et al. 2013). Therefore, individuals with extra digits were indeed present within a variety of populations and could have been the chosen subjects of artists.

Polydactyly in art

Polydactyly has been represented in art around the world (Emery and Emery 1994), with some of the earliest examples coming from the American southwest where hands and feet can be found in ancient cave paintings with extra digits. The occurrence of polydactyly in the American southwest has been corroborated by the osteological analysis where there have been at least six cases of polydactyly identified in the skeletal record (Case et al. 2006). Therefore, the renditions in art are based on exposure to the anomaly in life. Several famous works of Renaissance art demonstrate polydactyly, such as Raphael’s painting La Belle Jardinière (Paris, Musée National du Louvre) from 1507 where the left foot of St John and possibly the Virgin display six toes (Mimouni et al. 2000). In another work by Raphael, called The Marriage of the Virgin (Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera), painted in 1504, polydactyly is represented on the left foot of the bridegroom, Joseph, the only barefoot individual in the image (Mimouni et al. 2000, Albury and Weisz 2011). Mimouni et al. (2000) suggest that the models Raphael used for these paintings displayed the extra digit and further, that this may indicate that the child from one painting and the man in the other are related (for responses to this see Lazzeri 2010).

Polydactyly in Chalcolithic Cypriot figurines

Turning now to the evidence for polydactyly deriving from the anthropomorphic representations of the Chalcolithic period on Cyprus, an interesting picture emerges. The vast majority of Cypriot Chalcolithic figurines lack modelled hands and feet and the depiction of digits, fingers or toes, is fairly infrequent. Therefore, the observation of extra digits on several figurines and figurine fragments becomes more significant, particularly given the low rate of survival of these extremities. The repertoire of figurines can be divided into three groups based on their raw material: clay, hard stone (e.g. limestone, diabase, andesite) and picrolite, a soft serpentinite stone. The figurines typically survive in a damaged state or as small fragments, complicating identification and interpretation. In general, studies of the Chalcolithic period in Cyprus are dominated by excavations in the southwest of the island and therefore, the figurines discussed in this paper are exclusively from that area. This means that a regional artistic motif cannot be ruled out for any conclusions regarding representation of the deformity. The repertoire of Chalcolithic figurines examined by Winkelmann2 will be presented below, grouped by their material type: picrolite, clay and hard stone.

Picrolite figurines

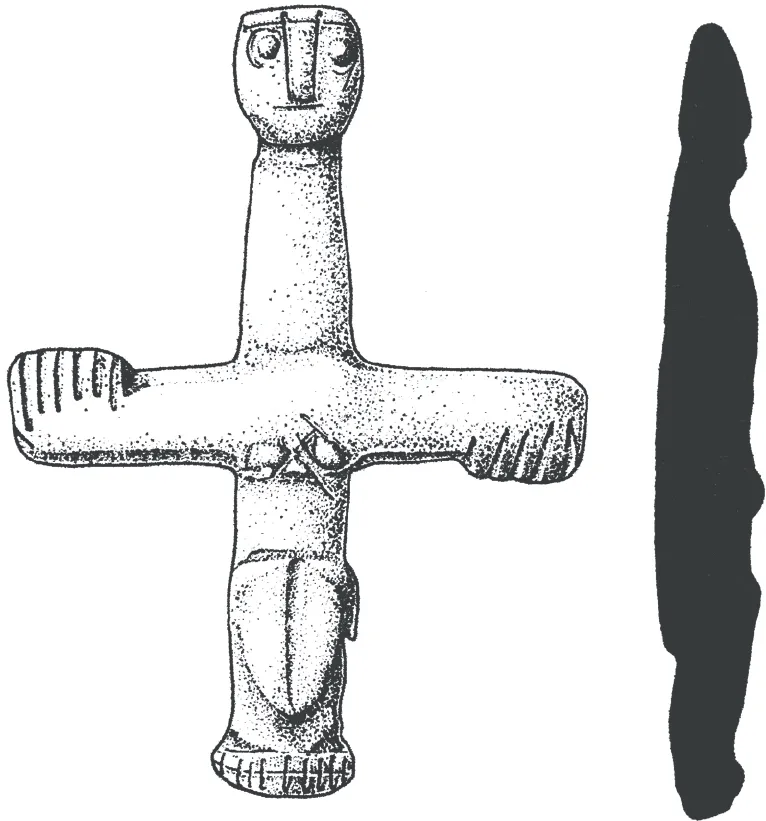

The most well-known anthropomorphic depictions of the Chalcolithic period are the cruciform figurines with the most popular example being the “Yalia” figurine (Dikaios 1934, 16, pl. vi:1). The assemblage of picrolite figurines examined by Winkelmann is composed of 251 cruciform figurine pendants and figures (for the distinction between figure and pendant see Vagnetti 1974, 28 and Winkelmann forthcoming). Like the clay and stone figurines, the picrolite cruciform figurines do not usually possess unambiguously shaped hands. Feet are typically represented, but tend to be carved rather schematically. Within the entire picrolite repertoire, 19 cruciform figurines are depicted with fingers and/or toes, with the latter occurring more frequently. This represents 7.6% of the entire assemblage. These are mainly of the “Salamiou Variety” (Vagnetti 1974, 29).

The representation of digits is not necessarily linked to the size of the particular item. For example, one of the smallest cruciform figurines (Vagnetti 1980, no. 6), with a height of only 4.0 cm, has five well-defined toes (at least on one foot), whereas one cruciform figurine with exceptionally wide feet (Paphos Museum 2125 – height of 6.0 cm) has only four toes represented (Flourentzos 1990, 44, cat. no. 36). However, the former may be an exception as usually the under-representation of digits does tend to occur on smaller figurines. Therefore, a deliberate depiction of oligodactyly (missing digits) cannot be stated with certainty; however, polydactyly is more likely to be a conscious choice.

There is only one case, derived from Kissonerga-Mosphilia, where a picrolite figurine clearly displays polydactyly, representing just 5.3% of the repertoire of picrolite figurines with digits rendered. This figurine has fingers indicated by incisions, five on one hand, but seven on the other (Goring 1998, 181, KM 1052; Peltenburg et al. 1998, fig. 83.9; Fig. 1.1). Taking into account the size of this specimen, at only 7.0 cm in height, it seems that polydactyly was deliberately represented (Winkelmann forthcoming).

Figure 1.1: Picrolite figurine with seven digits on one hand (after Peltenburg et al. 1998, fig. 83.9).

Clay figurines

Winkelmann examined a total of 191 anthropomorphic clay figurine specimens from the Chalcolithic period, most of which are highly fragmentary. Of this collection, 26 possess modelled hands or feet. The relatively small number of figurines with hands and feet rendered is somewhat curious given the malleability of clay. Overall, only 15 of these figurines are furnished with fingers, toes or both. That corresponds to 7.9% of the whole repertoire of clay figurines. Extra digits are observed on three figures, which represent 11.5% of all clay figurines with modelled hands or feet.

One of the clearest recorded examples for the modelling of multiple digits in clay is on a limb fragment from Kissonerga-Mylouthkia (Goring 2003, 171, 175, pl. 13.14, KMyl 307; Fig. 1.2). It is ambiguous as to whether it originally belonged to an anthropomorphic or zoomorphic figure. While Goring favours the zoomorphic interpretation, the lack of zoomorphic figurines which possess limbs of this shape suggests that it is an anthropomorphic figure. This interpretation is supported by anthropomorphic birth figures from the nearby site of Kissonerga-Mosphilia which have similar extremities (cf. Peltenburg et al. 1998, fig. 85.5). The limb from Kissonerga-Mylouthkia ends in a paw-like terminal with seven deeply incised grooves indicating eight digits, whether these are fingers, toes or claws (Goring 2003, 175).

The second example is an arm and shoulder or leg and thigh fragment from Erimi-Pamboula (ER 1056). It is described as having “five incisions at [the] extreme end for fingers” (Bolger 1988, 109, cat. no. 20), which reflects six fingers. Unfortunately, the published illustrations (photo and drawing) do not show the object at an angle where all digits are visible, therefore no further interpretation can be drawn at this time.

Finally, the third example of polydactyly in ceramic figurines is a leg fragment of a seated figure from Kissonerga-Mosphilia (KM 507) which is described as having a “paw-like foot with five deep incised cuts” (Goring 1998, 185). This again would represent six toes. As in the previous case, the illustration available does not show this irregularity (Peltenburg et al. 1991, fig. 29: KM 507). Overall, of the 12 clay figurines which possess digits, approximately one-quarter display evidence of polydactyly.

Figure 1.2: Ceramic figurine with eight digits rendered (after Peltenburg et al. 2003, pl. 13.14).

Stone figurines

Winkelmann has identified 84 stone objects as figurines or fragments of figurines from Chalcolithic excavations. The anthropomorphic figures are carved from stone such as limestone, diabase or calcarenite and are fairly schematic in form. Barring one special exception described in the next paragraph, none of the figurines included in this sample of 84 objects have modelled hands and very few show modelled feet, let alone digits of any kind.

Currently, only one known anthropomorphic stone figurine has elaborately carved feet. This figure, now housed in the Getty Museum, Malibu (Karageorghis et al. 1990, 32), is 39.5 cm tall and is the largest known complete limestone statuette of the Chalcolithic period (Thimme 1976, 565, cat. no. 573; Fig. 1.3). It is an extremely expertly worked stone figurine. It stylistically combines the cruciform figurine shape of the picrolite specimens with the pronounced femininity (pendulous breasts, fairly broad hips) usually characteristic of figurines and statuettes made of hard stones (Winkelmann forthcoming). Each foot is equipped with six finely carved, well-defined toes.

Figure 1.3: The Getty Lady, with supernumerary foot digits (digital image, courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program).

The unusual number of digits cannot be considered coincidental due to the skilful rendering of the object. Additionally the workability of the material and the size of the object must be considered, particularly in light of the fact that it is the only hard stone specimen to display more elaborately carved feet. The size and the skill required to carve this figure points to it being a special object for the Chalcolithic people – and it was consciously rendered with an extra toe per foot.

While the representation of digits is, overall, quite limited amongst the Chalcolithic anthropomorphic figurines, there is a relatively high occurrence of the depiction of anomalous numbers of fingers or toes. The representation of polydactyly appears to be a deliberate cho...