![]()

1

General

The Japanese victory over Russia in 1905 spawned a number of “lessons learned,” some accurate, some erroneous, that would inform Japanese doctrine and organization for the next forty years. Among those, some were contradictory, leading to rancorous feuds within the Army leadership that continued into the Second World War.

Certainly there was an initial feeling that an opening offensive, if sufficiently devastating and awe-inspiring, could cause a much larger opponent’s will to falter and lead to a quick victory. This had clearly happened in the war, but there seems to have been little recognition that the Russian social and government structure at the time was already rotten to the core and about to implode. There was also popular, although not universal, sentiment that the war had been won largely as a result of the intangible samurai ethic unique to Japan.

Japan’s role in World War One was minor, but many Army officers followed the fighting on the Western Front closely. As a result, where previously there had been various disagreements among the Army leadership on various issues, the different cliques now tended to coalesce into two main schools of thought. One, the traditionalists, continued to believe that Japan possessed a unique advantage in the warrior ethos of its people, and that doctrine should therefore be built around ferocious, close-quarters infantry combat, preferably featuring the bayonet. The reformers tended to look at the carnage of the Western Front and see how modern technology, particularly when integrated into a team, had slaughtered unsupported infantry. Similarly, the traditionalists continued to believe that an opening offensive of spectacularly overwhelming violence and speed could quickly break the will of an opponent, and to that end they favored the retention of the large square divisions that could absorb casualties and keep fighting, at least in the short term. The reformers tended to believe the next significant conflict could degenerate into a long war of attrition, for which Japan would not be suited without industrial modernization. They also advocated reorganization of the Army into smaller triangular divisions, providing a better firepower ratio and more flexibility in employment.

A swirling and bewildering array of cliques, associations and informal groups, many of which loathed each other, muddied the waters of Japanese doctrine from World War One through the mid-1930s. Conservatives of varying flavors, however, were the dominant force until 1936. In February of that year hot-headed young officers of the 1st Division launched a coup in Tokyo in the name of traditional martial values. When the coup collapsed after four days the reformers took advantage of the opportunity to discredit many of their opponents.

Nevertheless, the dominance of the conservatives through the mid-1930s resulted in considerable organizational stability. Through the early 1920s the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) was built upon eighteen regional districts, each of which maintained allotted forces through conscription, training and maintenance of reserves, plus the Imperial Guards district in Tokyo, which recruited from throughout Japan. Two further districts (19th and 20th) were formed in Korea in 1915 to administer the Japanese now resident there as well as Korean volunteers. In 1924, however, four divisional districts (13th, 15th, 17th and 18th) were abolished in their entirety as an economy measure.

Each district maintained a division and other smaller elements at peace strength through conscription of local male residents in their twentieth year for a two-year term of service. On completion of this active duty a soldier was released to the “first reserve” where he remained liable for recall for another 15 years. Those males not needed to fill out the district’s units and those of a lower physical quality were given some initial training (not to exceed 180 days) and immediately released to the “conscript reserve” where they remained liable for call-up for 17 years.

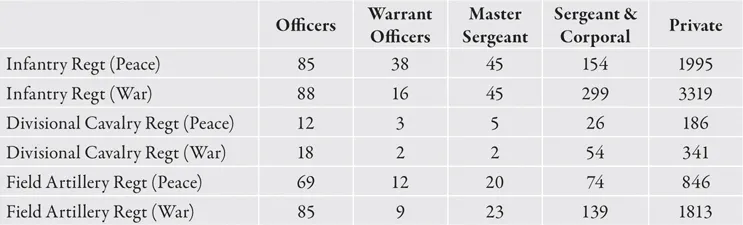

The division resident in a particular district carried the same numerical designation as that district. It was normally maintained at peacetime strength, which was generally about two-thirds of its wartime strength. In order to facilitate expansion the officer corps was usually kept at a higher level and the number of privates at a lower level. Examples of peace and wartime authorized strengths for 1937 show this clearly: In addition to the division, most districts also maintained a portion of smaller units required by the army as a whole, such as medium artillery regiments, cavalry brigades, anti-aircraft artillery regiments, etc., as well as administering the local coast defense (“heavy artillery”) regiments.

In addition to the division, most districts also maintained a portion of smaller units required by the army as a whole, such as medium artillery regiments, cavalry brigades, antiaircraft artillery regiments, etc., as well as administering the local coast defense (“heavy artillery”) regiments.

When a division (or other unit) was needed for service outside the district area two options were available. The quickest method was to bring the existing unit up to full (war) strength through the recall of reservists or an expanded intake of conscripts. The division would then depart, leaving a small cadre behind in the district to operate a “depot division” that would carry on the normal territorial functions, such as conscription, training, etc. Although quick, this method caused considerable disruption to the district operations. The preferred method, if time was available, was to create an entirely new field division in the district through conscription and recall, leaving the original division behind to carry on its territorial functions.

While the traditionalists in the Army hierarchy placed most of their faith in the perceived warrior ethos of Japan, that did not mean they disregarded the advantages of firepower altogether. Indeed, they keenly recognized the need for infantry weapons and light artillery to support the offensive. The infantry received three new weapons that significantly enhanced their small-unit firepower in 1922, the most important of which was a light machine gun that could accompany the rifle platoons and provide a base of mobile firepower. The other two provided high-explosive fire support at the battalion level, a 70mm mortar for area targets and those in defilade, and a 37mm gun for point-type targets. Although the Type (Taisho) 11 light machine gun was later to prove less reliable than most, the IJA’s infantry in the 1920s was generally as well armed as any in the world.

Through the 1920s the IJA infantry closely resembled its western counterparts, but maneuvers highlighted the need for even more effective close support of the infantry if they were to execute their vaunted maneuver and assault role. The result was the development of two uniquely Japanese weapons. The Type 89 grenade discharger was adopted in 1929 and could fire hand grenades and special 50mm projectiles from a hand-held tube. Three years later the Type 92 battalion gun was introduced to replace both the 37mm flat-trajectory gun and the 70mm mortar.

The artillery enjoyed its own modernization program in the late 1920s, launched largely to take advantage of technology newly developed by the Schneider firm. Not surprisingly the light artillery was accorded priority and the first results were the Type 90 (1930) 75mm field gun and the Type 91 (1931) 105mm field howitzer. A 105mm field gun followed in 1932 and finally a 150mm howitzer in 1936. The 75mm gun was a modified version of a Schneider weapon and was placed in local production immediately, while the 105mm howitzer was a direct copy of the French original and initial lots were purchased from France until indigenous production could begin. The 105mm gun and 150mm howitzer were placed in production as well, but only at very low rates.

Manchuria Beckons

The Army’s expansion plans were far from academic. Beginning in 1907 the IJA had rotated each of its divisions through a 2-year tour as the garrison division in Port Arthur, providing the “muscle” behind the Japanese claims to Manchuria, and in 1919 the headquarters supervising this area was named the Kwantung Army. The garrison division led a rather sedentary life, since the Japanese did not officially “own” Manchuria, but only the railways running through it. To guard their property, a right extracted from China in 1915, the IJA formed six independent garrison battalions of railway guards, reduced to four in 1925 but restored to its former strength in 1929. These railway guards quickly developed a reputation for mobility and initiative in conducting hard-hitting operations to support or chastise various Chinese warlord factions.

Through the 1920s the Kwantung Army had become increasingly involved in local Chinese politics, only rarely bothering to tell Tokyo what it was doing. It used its forces, mostly the garrison battalions, to shield some favored warlords from their enemies, and assassinated others. By 1931, however, several factors converged to push the Kwantung Army to even greater stretches of its authority. The wide open, often fertile, spaces of Manchuria beckoned to many Japanese both in a romantic sense and as a source for future Japanese autarky. The Japanese had had wide latitude in Manchuria due to the fluid situation created by feuding Chinese warlords, but looming on the horizon was the prospect of a unified China under Chiang Kai-Shek. Warlord armies the Japanese held in contempt as corrupt and inefficient, but a unified China under a dynamic leader might be a different story. If Japan was to secure Manchuria it would have to act quickly. The government in Tokyo was reluctant, but the Kwantung Army had no such doubts.

The forces available to the Kwantung Army were scanty....