![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE EFFECTIVE LEADER

In the introduction, we presented some examples of poor leaders. But what constitutes good leaders? What do they look like? How do they act? Who is best suited to be a leader? How can I tell whether or not I work for a good leader? If I am in a leadership position, what should I do? These are all fair questions to ask as we set out to create good leaders.

As you will hear from us time and time again, there is a process for everything, including the process to become a good leader. When we think of a person who is a good leader, we imagine someone with good character and a solid foundation of moral traits and ethical behavior.

On top of this foundation, a good leader also has a keen perspective and an eye for balance. Once you put all of this together in one package, you have yourself a complete leader. There is a process to becoming a complete leader, and we’d like to share that with you.

Since everyone has unique past experiences that give us all different perceptions, we need to start our discussion with a common understanding of terms so we can all play from the same sheet of music. There is a need here for a formal discussion, because there is a process to becoming a complete leader, and that process demands that we cannot simply do this “off the cuff.”

In this book we refer to the term leader or informal leader as anyone who feels they are a leader. If you think of yourself as a leader, then we are talking about you. Positional leaders or supervisors are people who occupy formal leadership positions in an organization, such as a first-line supervisor or senior executive.

Anyone in an organization can be a leader, but most are informal leaders, meaning they do not get paid to supervise. The terms worker, employee, and subordinate refer to those individuals who work for the positional leader in an organization; those terms are used interchangeably in this book.

A GOOD LEADER NEEDS BALANCE

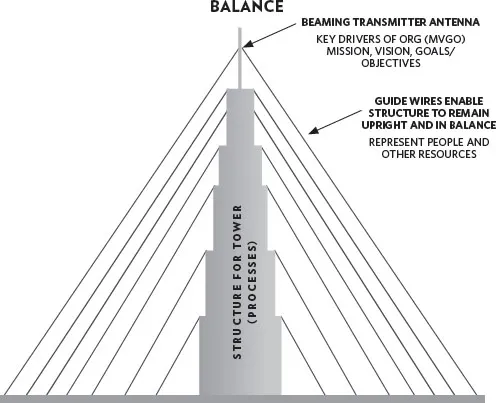

In order to transmit a signal, the structures (proccesses) must be well constructed and held in complete balance with guide wires (people & other resources) in order to be able to transmit (achieve their key drivers).

The first type of balance we will discuss encompasses the entire organization. A balanced approach to organizational leadership is crucial for anyone striving to be a complete leader. If a senior positional leader overmanages one area of an organization too much, the other areas will suffer from neglect.

Balance at the organizational level of leadership is also important for understanding both the present and the future of your company. Some leaders focus on current operations and fail to set goals for the future; this type of imbalance is dangerous because it is a nearsighted approach that can prevent the business from growing.

Leaders who are focused on the future of the company conduct strategic planning sessions, analyze external market conditions, and formulate visionary strategies. Without analyzing the future of a business, leaders will not be able to take advantage of opportunities that may arise. They will be more susceptible to external threats as they have never prepared for the future environment.

On the other hand, some leaders focus too much on what they want to achieve in the future and lose sight of the current state of their company. This type of imbalance is equally dangerous, because if a company fails to perform, it may not be around to see the future.

By maintaining proper focus on current operations, leaders will be able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the company and understand why the organization is performing or lacking in certain areas. These insights will aid planning, both in the current state of the business as well as the future.

Ultimately the balanced organizational approach to leading ensures that leaders have the right information. This information in turn enables sound judgment and quality decision making. By maintaining an overall balanced approach to leading a company, a leader can ensure the organization is healthy in its entirety.

The complete leader also possesses a second type of balance at the personal level when dealing with subordinates: a balance of influence. It is impossible to talk about influence without talking about power, so here goes.

There are two types of power we need to briefly discuss. The first is legitimate power, which is formal authority that comes with a position such as first-line supervisor (French & Raven, 1958). If you do something because your boss told you to, then your boss used legitimate power to influence you.

The second type of power is called referent power. Referent power emerges over time as you form positive, meaningful relationships with other people (French & Raven, 1959). Referent power is much stronger than legitimate power and can be acquired by anyone, not just supervisors. If you ask a coworker for help and that person aids you because you have developed a strong personal relationship with them, then you have influenced that person with referent power.

Although complete leaders rely more on referent power, they do understand the important balance between responsibility and legitimate power. Organizations legitimize positional leaders by empowering them with the authority, or legitimate power, to perform their assigned duties.

In order for organizations to be effective, positional leaders must then be held accountable for performing these duties or responsibilities within the position. Positional leaders must align their priorities with what is best for the organization. They must also make sound decisions based on ethics, morals, and company policy.

The complete leader also recognizes when there is an imbalance between the responsibilities assigned and the level of legitimate power or authority needed to perform his or her duties. Too little authority can undermine the positional leader and make them appear to subordinates as being weak or incompetent, as they do not have enough legitimate power to fulfill their normal duties as a supervisor.

For example, Chris was tasked by his Air Force senior leader to gain engineering approval to perform a critical flight test for an aircraft navigation device. His boss gave him only one week to gain the approval, which was quite a restraint.

The normal process for gaining this type of approval took at least six months. Chris recognized an imbalance between responsibility and legitimate power, even though he already had built a high level of referent power with other workers. In this instance, Chris did not have the legitimate power to reprioritize the work of his coworkers to accommodate his urgent need and work his task first.

Chris recognized that without a reprioritization of the other workers’ tasks, there was no way to gain an engineering approval in the allotted time. Once he communicated this imbalance to his senior leader, the boss sent an email to the entire organization and informed them that Chris was personally working on his behalf; he also told them they should treat Chris as they would the senior leader himself. This one email gave Chris enough legitimate power to ask others to give his project priority, which allowed him to accomplish the task on time.

Leaders work best when they are assigned responsibility and legitimate power in somewhat equal amounts (Yukl, 2010). The more responsibility a positional leader has, the more legitimate power he or she will need. A complete leader will recognize an imbalance between power and responsibility, if one exists, and take steps to remedy the situation.

Complete leaders will also use their delegated authority to benefit the organization. They will use legitimate power when fulfilling the assigned duties of the organization and nothing more. The complete leader relies on referent power to influence others and leverages strong relationships to get things done.

Eisenhower’s thoughts about leadership reinforce this concept: “Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it.”1

BALANCING LEADER BEHAVIOR WITH WORKER EXPECTATIONS

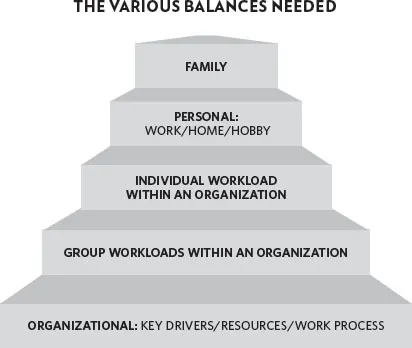

Shows how organizational balances impact individuals and families.

Subordinates expect positional leaders to use legitimate power to make necessary decisions. If a positional leader fails to do so, he or she creates a dangerous imbalance between leader behavior and worker expectations. If this imbalance occurs, supervisors can easily find themselves losing respect and morale from their subordinates.

Even worse, if the leader fails to make a decision that is necessary, workers may feel as though it is the responsibility of the workers themselves. This lack of action by the positional leader creates confusion, as no one is sure who should take the responsibility and make the decision. This scenario can result in power-jockeying if more than one person thinks they should be the one to act.

In his witty short called “A Responsibility Poem” about a fourperson team, Charles Osgood characterizes this perfectly (quotation marks added):

There was an important job to do and “Everybody” was asked to do it. “Everybody” was sure that “Somebody” would do it. “Anybody” would have done it, but “Nobody” did it. “Somebody” got angry because it was “Everybody’s” job. “Everybody” thought “Anybody” would do it, but “Nobody” realized that “Anybody” wouldn’t do it.

We have found that many positional leaders are continually asking themselves, “Should I, could I, would I?” when it comes to making decisions, accepting responsibilities, and leading people. The effective leader is usually more aggressive and asks for forgiveness rather than permission when it comes to responsibility. This approach usually garners more respect and esteem from their workers as a result.

Although exercising legitimate power is necessary for positional leaders to maintain balance and fulfill assigned responsibilities, the complete leader utilizes referent power to the maximum extent possible. For this reason, it is important for leaders to develop positive and meaningful relationships with workers.

It is impossible to be a complete leader by possessing only positional or legitimate power. Using only legitimate power, a supervisor can tell a subordinate to perform a task, and it will likely happen. But once the task is accomplished, the worker will stop any further activity. If the supervisor had strong referent power with the worker, then the subordinate would be more committed to the task, which would likely increase the quality of the work.

If the leader had strong referent power, the employee would also be more likely to provide feedback to the supervisor if there were any problems along the way. The worker would also communicate if there was a better way to accomplish the task or if the worker discovered new information that would benefit the supervisor or the organization. Without referent power, the positional leader would likely get no feedback.

A GENERAL’S REFLECTION

Back when I was a one-star General, I was in charge of 27,000 logistics personnel from three different military service branches. We were stationed at an Army post in Kuwait, and we supported combat operations in the Iraq theater during OPERATION: Iraqi Freedom.

Early in my tenure I began visiting different units in my organization because I knew from past experience that the troops needed to see their senior leader engaged. I always took Archie, my Command Sergeant Major (CSM), with me because he was the senior enlisted leader and was a great second set of eyes. During these visits I would “kick the tires” by walking around and talking to the officers serving as unit positional leaders, and Archie would “check under the hood” by visiting some of the younger enlisted troops where they worked and slept.

I remember this one Friday when a new unit was assigned to my command. I immediately visited them, and during my nickel tour, as I talked with some of the leaders, I noticed that many of the officers who were positional leaders were in charge of other officers of the same rank. I found this odd, as usually the positional leaders would be higher ranking.

When examining the behavior of the positional leaders I got the impression that they were not acting the part; it was almost as if everyone was in charge, but no one was in charge. Also, when I asked probing questions I got the impression that they were “blowing smoke.” Later, I compared notes with Archie and told him that I had the feeling that something wasn’t right. He said, “Sir, I’m seeing the same thing.”

I’ve never been one to sit on a “hunch,” so I called in an outside inspection team and ordered an immediate health and welfare inspection on the unit. The inspection team did a deep dive into the unit and then reported to me later that night with their results. The commander of the inspection team brought some astonishing results that validated my suspicions. I felt like they would come back with something along those lines, but their findings actually overwhelmed me.

The results were three legal pages of violations—ranging from violations of General Order #1 (brokering alcohol and pornography in theater), to sexual harassment, fraternization, arson, and dereliction of duty.

The First Sergeant was recorded on video as having one of the female soldiers performing a lap dance at the mobilization station in front of dozens of members of the organization during a Christmas party. Every Friday night, the officers of the unit would replay the video during a party, which was how they got caught by the inspection team.

Several of the key leaders of the unit were running a pornography and alcohol ring. Mind you, both are illegal in Kuwait, as it is a Muslim country. They were selling pornography and alcohol to other inhabitants of the base they were living on, and jeopardizing every one of their customers.

Following the brief from the inspection team, I...