![]()

PART I ACTION PAINTER

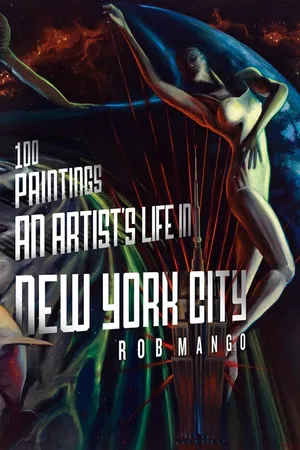

26. Action Painter. 2005. Oil on canvas. 84 × 40 in. Collection of the artist.

![]()

Surrealism and a World Record

A life-changing experience: gazing into Larry Rivers’ painting Lions on the Dreyfus Fund III. I encountered it at The Art Institute of Chicago as a 14-year-old student in 1964. It spoke to me in a language of paint that I instinctively understood. From that moment on, painting for me was breathing. I filled volumes of portfolios and rooms with canvases, objects and drawings. Many of these works have survived, but I did not consider myself good enough to sign a painting. (In spite of my vociferous objections, my wise and caring father often added my name in the lower right-hand corner.)

27. Homage to Dada (front, back). 1985. Fiberglass legs; steel armature; lead apron, box and skirt; X-ray; internal light; beating heart. 70 × 30 × 30 in. Collection of the artist.

Two years later, I stood in line at the Institute and met a new idol: Marcel Duchamp, then nearly 80 and in the last years of his life. He signed a poster I had in my hand, an image of one of his “ready-mades,” using a pseudonym: Rrose Sélavy. I was ecstatic. I had discovered Duchamp’s work the way I discovered so many artists—by wandering the halls of the Institute. That year was the origin of an artistic sensibility that would later ripen and is still maturing. I saw no reason then, nor see one now, to cage or limit this sensibility.

My father was an industrial designer, my mother a self-educated reader who introduced me to poetry over the breakfast table—Walt Whitman, T.S. Eliot. Very early, I was seduced by the power of both images and words; they nurtured a secretive and transformative imagination, always looking and always finding. I was riveted by the revolutionary doctrine of André Breton: “I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak …”

These words set me on fire, as they do so many young artists just coming into the wealth of the psyche. I had already embraced the image-driven, silk-screened, splattered, encaustic, billboard paintings of the New York School: Duchamp’s first graduating class (via Black Mountain College). I recognized the symbolic and literal references as indicators of meaning. These artists and their counterparts in Europe simply chose an image, no context required. This was the heart of Duchamp’s action, the essence of the found object: Simply select. These meaning-laden references were signposts along a pathway. Following my eye, I had entered the great labyrinth of ideas.

I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak…

—André Breton

“Manifesto of Surrealism,” 1924

My initial attraction to the post-World War II American school of painters expanded. Their overall look and feel influenced me; their visual aesthetic enraptured me. I understood the New York School art stars and I appreciated their mission but I craved something more. American society was becoming commercial and materialistic. These pioneers of postwar American art sought an expression of that kind of subject matter, some of which, in retrospect, seems naïve, but remains a chronicle of the changing complexion of American life in the 1960s. Ultimately, Robert Rauschenberg went political, Andy Warhol became a curious dinner party gadfly of the rich and famous, and Jasper Johns remained the thinking man’s painter. Larry Rivers’ work still drives me to my knees. I loved their unfettered American energy and idolized them all, including Jimmy Rosenquist—who later became a friend and neighbor in Tribeca—and, of course, Roy Lichtenstein.

By 1967, I was ready to embrace surrealism—transportive, daring, imaginative and gorgeous—but in the end I found it to be more drama than substance, hollow without the raw purity of Dada. Although technically masterful, and of noble spirit, the surrealists did not sustain my interest. Max Ernst, Salvadore Dali and others understood the unconscious realm they portrayed. But because they set out to describe it, rather than become it, they were doomed.

28. Ferris Wheels for the Insane. 1982. Oil on canvas. 84 × 84 in. Collection of the artist.

29. Home for Humanity. 1977–80. Mixed media kinetic construction with neon. 78 × 78 × 15 in. Collection of the artist.

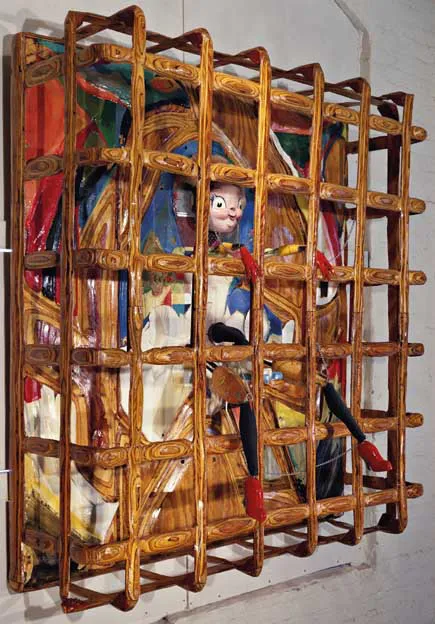

31. For the Women’s Movement. 1977–1980. Carved and laminated wood, oil paint and mixed media. 65 × 65 × 10 in. Collection of the artist.

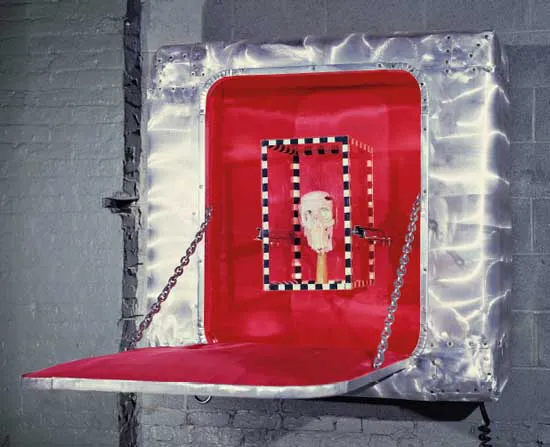

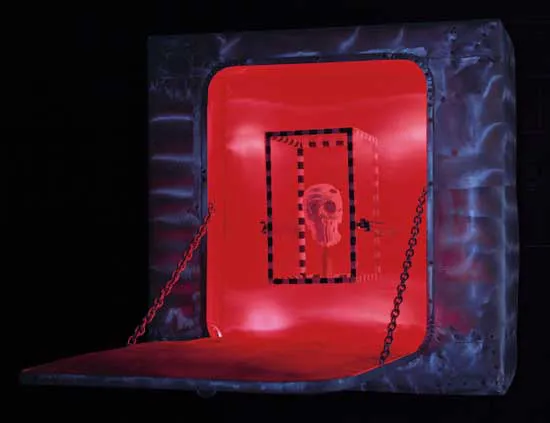

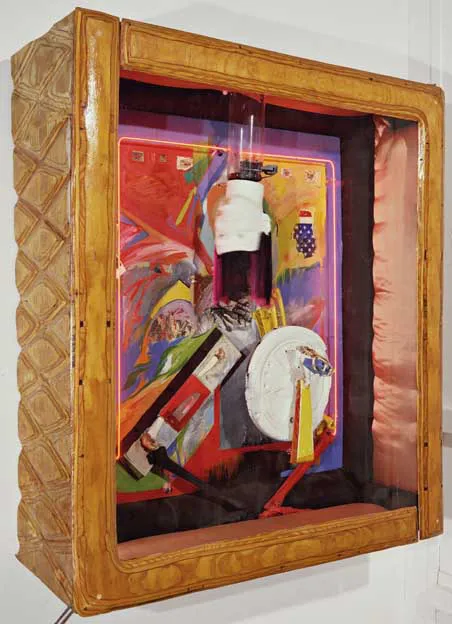

30. Visiting Artist. 1977. Brushed aluminum exterior, stuffed satin interior, sculpted skull, sliding plexiglass enclosure. 48 × 48 × 19 in. Collection of the artist.

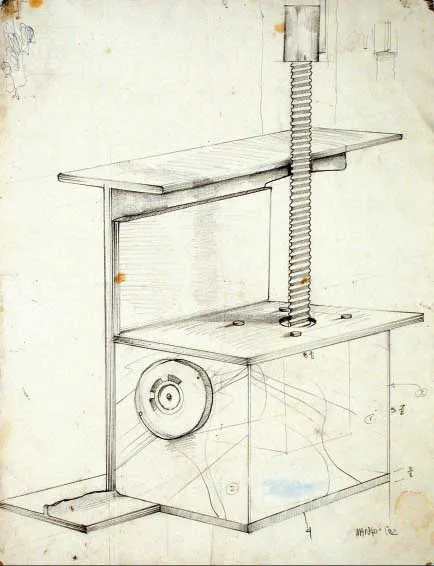

32. Fools Gold (working drawing). 1981. Graphite on paper. 18 × 24 in. Collection of the artist.

33. Fools Gold (two views). 1981. Wood, steel, motorized gears, neon, plastic. 28 × 11 × 4 in. Collection of the artist.

34. Aspects of Archeology. 1985. Three-dimensional mixed media kinetic construction, neon and paint. 60 × 50 × 24 in. Collection of the artist.

35. The Enola Gay. 1987. Oil on canvas. 60 × 72 in. Collection of Sally and Al Ordonez.

I had existential needs that surrealism spoke to, but I wanted to transform those needs and insights from literature and theater into an art object that would live on the wall.

Yet I learned technique from many of them, and they spoke to me of my European heritage. The sinuous classical oil surfaces of European masters were part of my practice already. I’d spend years copying the color and brush strokes of great painters, working my way forward from the Italian Renaissance to impressionist masterpieces. To embody the surreal, of course, is a dicey undertaking. Surrealism’s domain is the mind’s deepest recess, where the death instinct resides, along with sex: Surrealism takes much of its power from Eros and Thanatos. I had existential needs that surrealism spoke to, but I wanted to transform those needs and insights from literature and theater into an art object that would live on the wall. Over the next couple of years, I found inspiration in other art forms that merged symbol, movement, poetics, theater and, most of all, graphic appeal: Federico Fellini’s 8½, Allen Ginsberg’s recording of Howl, the installations of Edward Keinholz. I read all the Beat poets and writers and went to Ginsberg’s and Gregory Corso’s readings in Chicago, feasted on William Burroughs, and frequented the surreal and underground cinema, particularly the French and the great Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel. I read the symbolist poets and the French existential philosophers.

My ultimate destination turned out to be unconscious structures of the mind, described by Freud in The Ego and the Id. During those avid teen years, I was analyzing all types of form and design in nature and the manmade world: radial, spiral, bilateral symmetry and asymmetry. I viewed the cracks in the sidewalk and formations of passing clouds as more than accidental. I was drawn to the threshold where rationality confronts the arbitrary. I came to Freud via Nietzsche: “I love him who lives in order to know.… I love him who labors and invents, that he may build the house for the Superman, and prepare for him earth, animal, and plant: for thus seeks he his own down-going.” I seemed to understand this innately. A powerful creative faculty was making itself known to me, a design theory evolving from what lay within. I would spend my life “down-going.”

As I write, I am recalling the trek to the frontier taken at a very early age—a frontier from which I suspected I would never return. It was necessary and it was dangerous. I was listening to the voice of a stubborn sanity unwilling to squeeze a widening awareness to fit the mold of normal life in the Chicago suburbs. Within the apparently illogical, accidental and chaotic, I sensed truth and saw beauty, both territories far more alluring than conventional life. I felt empowered by my sojourn. The madman was really quite sane—in fact, a genius. The net effect of my investigations would be the demystification of the absurd, the unknown, the insane and of chaos itself. I sought their inclusion within a painter’s intellect—or I should say, I allowed myself to see what was already entirely present.

The net effect of my investigations would be the demystification of the absurd, the unknown, the insane and of chaos itself.

What I was seeing was not in doubt, but I felt compelled to understand why I was seeing the world so differently than other kids on the schoolbus. I knew I would be required to create a new self. Painters and sculptors, writers and filmmakers, artists and thinkers of many eras pointed the way. I was not afraid.

As a high school student, I was enrolled in a Saturday class at the institute’s junior museum school (SAIC). I learned a great deal from a few excellent instructors. After the first semester I received a summer scholarship, and a year later I was teaching the figure drawing class to my teenage peers. One Saturday morning, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin strode rebelliously into a full class where a posed nude reclined. These strange creatures—“yippies,” they called themselves—passed out pamphlets inviting us to a gathering in Grant Park, which bordered the museum property. The Democratic Party was holding its convention in Mayor Daley’s town. Later in the day, the Grant Park riots occurred: cops on horseback vs. the yippies. The guys on horseback won. That night, the neighborhoods were ablaze.

The political ferment of the ’60s fed my art obliquely, and the yippies with their Dadaist acts (throwing dozens of dollar bills from the Visitor’s Gallery of the New York Stock Exchange, announcing their intent to levitate the Pentagon) were emblematic of what linked that period with the creative ferment of post-World War I Europe. The artist was a king and a joker, always a rebel. The artist had unassailable dignity because he was the first to throw it away in the search for truth.

I love him who lives in order to know. I love him who labors and invents, that he may build the house for the Superman, and prepare for him earth, animal, and plant: for thus seeks he his own down-going.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

“Thus Spake Zarathustra,” 1883

I had become a better draftsman than my teachers. They had no problem with that. Drawing was my life. Every summer, I worked as a mechanical draftsman in my father’s industrial design practice. The balance of my free time was spent freehand drawing at The Art Institute. I didn’t understand it at the time, but I was drawing from both hemispheres of the brain. I was seeing it all—as a dispassionate draftsman and as a passionate young artist.

The logical outcome of an unrelenting inclusion of all manner of form in creation is obsession. I had adopted the belief that painting was the thinking man’s game, yet I had a natural talent for drawing, painting and color. I drew, painted and sketched every night and spare moment. Ideas became paintings. Anything could become a painting. This was my credo: Never repeat myself. I was determined to always reinvent perspective. Every day had to be another approach, until I had thoroughly scouted the territory I claimed.

The obsession I felt as an artist was mirrored in a sport, track and field. I was born with the gift of speed, which became apparent at age 10, when, at the summer parish picnic against men of all ages, I won the traditional race across the ball field. Unlike the stereotype of the artistic or hippie personality circa the late 1960s, I was goal- oriented. A definition of success in the arts is subjective (aside from considerations of fame and money). On the track, however, it is absolute— the first one to the finish line wins. A measurable outcome … what a relief!

The tandem obsessions of art and running gave me balance. What they had in common, beyond the quest for excellence, was that both could be pursued in solitude, limited only by one’s dedication and tolerance for pain. My passion for art was matched by a high pain threshold and an insatiable desire to win races; breaking the tape at the finish line—my competitors significantly behind—remains one ...