![]()

1

THE VALUE OF A MAP

Start-ups are hot. We’re seeing not only more entrepreneurial businesses emerge in the twenty-first century but also a more diverse group of start-ups. Besides the college students, recent graduates, and serial entrepreneurs who have always occupied this space, a variety of other participants are becoming more numerous: corporate executives fleeing the world of big business to create something on their own; brilliant young people whose first or second jobs may be with start-ups; refugees from nonprofit, government, and other sectors who are attracted to the entrepreneurial adventure. Additionally, start-up fever is spreading geographically throughout the US and also the world. It’s not limited to Silicon Valley, Austin, and Seattle. Now startups, incubators, and accelerators are popping up in Pittsburgh, Chicago, Barcelona, and Shanghai. Tel Aviv, San Paulo, Sydney, and Bangalore now rank among the world’s top twenty start-up ecosystems, according to the Startup Genome Project.

In addition, entrepreneurs are launching these new businesses at a time of great volatility and unpredictability. In our increasingly global, digital universe, nothing stays the same for long. Trends come and go with lightning speed; new, dominant companies emerge seemingly out of nowhere; and what’s state-of-the-art today becomes hopelessly outmoded tomorrow.

Start-ups are hard. Very, very hard. They will likely test your creativity, perseverance, courage, and intelligence. Your relationships will also be tested—both within your company and with your family and friends. More than once, you are likely to be spent physically, emotionally, mentally, and financially.

This book will provide you with guidance, in bad times as well as good. It will give you a clear road map that will help you navigate the treacherous start-up terrain and make the journey to success as smooth and efficient as possible. This book will help you know with some level of certainty exactly where you are and what you need to be focusing on. I’ll also try to expose the many myths that are associated with start-ups, and I’ll try to point out the areas where you may need to alter your ingrained beliefs and patterns of thinking to increase the odds of both you and your start-up being successful.

More so than ever before, start-ups require a map to chart a course through innumerable and significant obstacles. As you’ll discover, a map is exactly what this book will provide.

KNOW WHERE YOU’VE BEEN, WHERE YOU ARE, WHERE YOU’RE GOING

Start-ups aren’t as random and chaotic as they might appear. If I’ve learned nothing else after thirty-five years of doing startups, it’s that they begin, progress, and end in predictable ways. On a granular level, of course, the unexpected often happens: a funding source suddenly dries up, and a new customer appears seemingly out of nowhere. If you take the long view, however, you can see patterns to start-ups—patterns that can prove invaluable to entrepreneurs, providing perspective and assisting in decision making.

These patterns provide a map that entrepreneurs can follow, and this map can make the difference between failure and success, between making a small and a large profit, and between having a flash-in-the-pan business and a sustainable one.

The value of this book is that it will help you become familiar with the start-up path. It will show you the markers along the way that will identify your particular point in the process and the best actions to take at this point. You’ll learn, for instance, what to do when your initial product falters—a common start-up occurrence. You will also learn when to use the knowledge gleaned from the failing product to introduce iterative—and eventually, more successful—versions of the original.

Once you know where you are on the start-up path, you are much better able to know what your next steps should be—as well as the common (but avoidable) mistakes often made at a particular point on the path. This knowledge is hugely valuable tactically, but it’s equally important psychologically. Too often, entrepreneurs give up prematurely when faced with surmountable obstacles, and they move forward aggressively when they should stop, reflect, and re-create.

Psychologically speaking, some entrepreneurs fold their businesses because it seems all is lost. When they are aware of the reality—they’ve just hit a speed bump—they can process the predicament, see it in context, and move forward rather than calling it quits. Similarly, some entrepreneurs take enormous and often unnecessary risks because they are caught up in the start-up mentality; they believe they must be overly aggressive if they’re going to be successful. In fact, there are times to be aggressive and times to be conservative, and if they know where they are on the start-up map, they can respond appropriately.

Consider, too, that in the start-up universe, you always have more tasks to accomplish than time or resources to do them. The scarcity of resources is often extreme given the enormity of the mission, so efficiency becomes a critical discipline. Therefore, allocating the right amount of money and energy to the right tasks at the right moment is crucial. With a map in hand, this allocation is much easier to do than when you’re flying by the seat of your pants and potentially flailing in too many directions.

As I noted in the introduction, I call this map the J Curve, and I’ll help you become more familiar with its components shortly. First, though, I’d like to tell you about a start-up journey that helped open my eyes to the concept of the J Curve.

NO STRAIGHT LINE FROM START TO FINISH

In 2007, my business partner, David Hehman, and I helped Sara Sutton Fell launch a company that focused on connecting people who wanted to work from home with employers who supported remote workers. Since my own company, LoveToKnow, was a virtual organization, I knew from firsthand experience the value of working from home and that a huge untapped pool of talent preferred this option to an on-site office job. We were all incredibly excited. I knew Sara was the perfect one to lead the company because she is smart, effective, tenacious, and a hard worker—I’d witnessed these qualities when she did some marketing consulting for me at LoveToKnow. She also cofounded another start-up called JobsDirect, so she knew the jobs space. Sara was a multitool player who could cover wide swaths of responsibility. Perhaps more importantly, she is a wonderful human being whom any savvy angel investor would trust. We teamed her up with an incredibly talented local engineer and another skilled engineer from India who helped with the original coding.

With great optimism, we released our first product, a curated selection of work-from-home jobs. Our proposed business model resembled that of other online companies featuring job sites: we charged prospective employers to post jobs and obtain access to our pool of job seekers.

Soon after the launch, however, we discovered that HR departments were tough prospective customers. They didn’t have much money, and they were not inclined to try new things. Generally, they were also suspicious of and resistant to the work-at-home market. Despite our best efforts, we weren’t having much success. While Sara maintained her optimism and persevered, the company was rapidly running out of money and not showing enough traction to justify investing more money. We plodded on for a few more months but were becoming more and more dejected, and then we discussed ending the venture.

Before doing so, though, we asked a simple question: Is there anything we are doing that is working? Sara pointed out that we had a huge number of job seekers who had created accounts and that they liked our site. As we reflected and discussed the situation, we recognized that we had proven at least one of our hypotheses: There was a huge untapped work-from-home labor market. They wanted and needed good jobs. Many competitive sites offering these remote jobs were often outright scams; in order to “work at home and make $xxx per day” you had to first buy the course or kit. No doubt, once these sites sold the kit, customers were disappointed with their subsequent “job” results.

Stay-at-home moms and others in our target market wanted real jobs, and we were one of the only sites that had them all in one place. So we decided to turn the model completely upside down, and instead of charging the prospective employers for job listings, we would charge the job seekers a monthly subscription. Because we made our service free to these employers, we began receiving great access to all of their remote jobs. Sara and her team quickly put up a test where we charged a nominal fee of fifteen dollars per month for job seekers to use our site. We obtained sign-ups immediately, and after a week, we became convinced that we could make real revenue. Today, FlexJobs is going gangbusters under Sara’s adept leadership and the technical prowess of the incredibly talented CTO, Peter Handsman. And perhaps most importantly, we have helped over a million job seekers in their search for remote and flexible work.

We experienced a similar pattern with other companies in which we invested. Before FlexJobs, I had assumed that most successful companies developed their business plan and went with it until it passed or failed. What I came to realize, however, is that the entire journey is a process. The product and associated business model is really simply a hypothesis (not a hard-and-fast product launch), and the results are not pass/fail or black and white, but instead produce feedback, providing essential information that increases the odds of success. I had an epiphany: Iterations count more than the original idea, feedback counts more than the sales numbers, and flexibility and agility are more important than commitment to the original idea.

The straight line from start-up to sustainable success is largely a myth (though of course there are exceptions to this rule). Instead, start-ups usually follow a path that resembles the letter J.

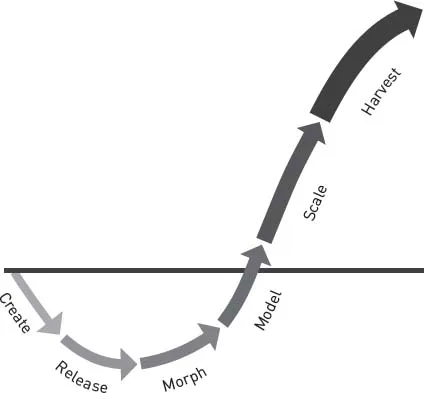

The shape of this six-phase curve suggests what differentiates it from other start-up models. As you can see, the base of the J represents the dip that occurs shortly after a company is launched. At first, the power of the business idea captures everyone’s imagination, and it garners money, team members, and other forms of support. Then, reality sets in, products take longer to develop than expected, customers don’t embrace the initial offering the way that was anticipated, the business model doesn’t quite work, and eventually money starts drying up. These are all tough hits to take, especially if you’re not prepared for them. Therefore, the dip is represented by the base of the J, and it’s where startups figure it out or they die. I call it the long, cold winter or, if I’m feeling more morose, the valley of death. Much of this book is dedicated to giving you strategies and tactics to get you and your start-up through that difficult period. Because once you are through it, you are into the steep upward slope of the J, and that is where the bulk of the value creation happens.

This curve is a reflection of start-up reality rather than an idealized progression. Each of the phases, listed in chronological order, reflect the challenges and opportunities that arise for all types of start-ups as they evolve. With this curve as your guide, you’ll be able to put your start-up’s experiences in context and have a better sense of what to do in response to these challenges and opportunities.

In chapters 2 through 7, I’ll look at each phase in depth. For our purposes here, though, I’d like to provide you with a snapshot of each phase.

Phase 1—Create

This first phase of a start-up may seem self-evident, but numerous nuances exist that, if addressed, can get you off to a great rather than a fatally flawed start. In the Create phase, the three key elements are the idea, the team, and the money. Not all entrepreneurial ideas are created equal. Some are much better than others, and entrepreneurs need to recognize that the best ideas aren’t manufactured, that superior technology does not automatically produce superior products, and that products succeed because they solve real problems or provide real new opportunities. So in this phase, start-ups must identify an idea that is going to be worthy of the entrepreneur investing their life’s energy, not to mention their savings.

Similarly, they must raise money like the dickens; underestimating the amount of funds needed is a common failing. Contrary to what some entrepreneurs may believe, this is one of the best times to raise money from various sources. I like to characterize this initial phase as “dreams unburdened by reality.” It can often be easier to raise funds while the excitement runs high and the story is virginal, as opposed to trying to do so when confronted by often-unforeseen challenges later in the process.

The team, too, can be a tricky proposition. Rugged individualism is a philosophy many entrepreneurs embrace, yet it can be counterproductive to start-up success. Putting together the strongest possible team with complementary skills and character traits is critical. Mistakes here will be hard to undo. Having a strong team of cofounders often serves start-ups better than solo entrepreneurs. Getting it right will make the endeavor both more successful and a lot more fun.

Phase 2—Release

Once the team, idea, and money are in place, it’s time to get the initial product out there. In this phase, some entrepreneurs suffer from procrastination and/or perfectionism. These are the enemies. You have to push products into the market even when your impulse is to do more research, tinker with their formulation, or build more features.

After the product release, the most successful start-ups are the ones who listen the hardest. They pay close attention to what customers are telling them—both positive and negative feedback—and use it in the next phase. During release, entrepreneurs can’t get too low or too high—they can’t throw in the towel because of a negative response or expand frantically because of a positive one.

Phase 3—Morph

In most endeavors, people generally don’t hit home runs their first time at bat. Generally, they don’t get it right until they’ve had sufficient experiences—including failures—and learned from them. The same is true for start-ups, and that’s why the Morph phase is so essential. In certain ways, it is the most important phase. This is where entrepreneurs take the feedback they’ve received after launching their initial product and make improvements, iterate, and/or pivot.

The goal here is to be flexible enough to move beyond the original idea and either make it better or use it as a stepping stone to something related but different. Admittedly, this can be difficult. Entrepreneurs tend to fall in love with their original ideas, and in this phase, they may need to alter or even largely abandon them. The keys to moving effectively through this phase are to listen and respond to customer feedback (it may be harsh, but it’s true) and produce one or more fundamental changes, which I refer to as morphs, as fast as you can. By adapting in this manner, you increase the odds of finding a product that thrills your customers—and your investors.

Phase 4—Model

In this phase, you’ll focus on nailing the business model. Your goal is to reach the point where if you put more investment money into the business, more cash will be generated. You need to get to the point where it’s obvious that this company will generate cash flow at some certain point. You do this by knowing and driving down all your costs—customer acquisition, engineering, and so on—and at the same time maximizing your revenue. The Holy Grail is a large positive operating margin and concomitant large positive cash flow. You may decide to invest all of that positive cash flow into growth, and that’s OK. But you should be honestly convinced the business model can and will generate cash. Otherwise you don’t yet have a business.

Phase 5—Scale

The Scale phase is where much of the substantial value is typically created for investors. However, this can be a tricky stage for some entrepreneurs, in that they need to leave behind their small and insular mentality and build out the company. More specifically, this is the phase where you assembl...