![]()

1

Introduction: Posthuman Perspectives in Roman Archaeology

Lewis Webb and Irene Selsvold1

Nothing I beheld in that city seemed to me to be what it was, but all, I believed, had been transformed into another form by a fatal murmur: the rocks I encountered were hardened humans, the birds I heard were feathered humans, the trees that surrounded the pomerium were leafed humans, and the liquid in the fountains had flowed from human bodies. Soon the statues and images would start to move, the walls start to talk, the cows and other animals of that species begin to utter prophecies, and from the sky itself and the splendour of the sun would suddenly venture an oracle.

Nec fuit in illa civitate quod aspiciens id esse crederem quod esset, sed omnia prorsus ferali murmure in aliam effigiem translata, ut et lapides quos offenderem de homine duratos et aves quas audirem indidem plumatas et arbores quae pomerium ambirent similiter foliatas et fontanos latices de corporibus humanis fluxos crederem; iam statuas et imagines incessuras, parietes locuturos, boves et id genus pecua dicturas praesagium, de ipso vero caelo et iubaris orbe subito venturum oraculum (Apul. Met. 2.1).

The Roman author Apuleius’ carnivalesque vision of the Thessalian city Hypata destabilises and blurs the boundaries between human and non-human beings, between the animate and the inanimate, questioning human ontology itself. Apuleius’ vision prompts a question: what did it mean to be human among and with other living and non-living beings in the Roman world? The Romans were entangled in the divine, non-human animals, plants, material objects, and the wider environment: they were relational beings, as we are today. Such questions and entanglements propel this volume on posthuman perspectives in Roman archaeology. Fundamentally, posthumanism is concerned with the entanglement, interactions, and relations of beings. Or, to borrow an expression from the inimitable Donna Haraway, ‘all the actors become who they are in the dance of relating’ (Haraway 2008: 25; emphasis in original).

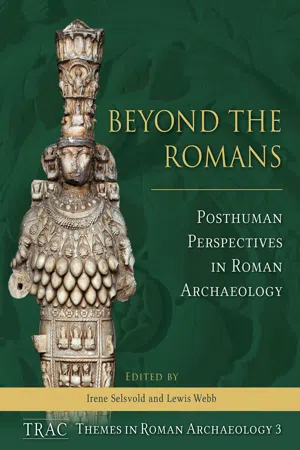

Gracing the cover of this volume is a material manifestation of such entangled interactions and relations: the so-called ‘Great Artemis’ (Große Artemis), a marble statue of the goddess Artemis from the Prytaneion in Ephesus dated to the Trajanic period. The ‘Great Artemis’ is crowned by a high polos depicting three temple façades with Ionic columns and a city gate flanked by two temple façades, winged sphinxes in the interstices of arches and columns and perhaps an altar flanked by crenellated ashlar walls, and winged griffins and torches. Her head is framed by a so-called nimbus with winged griffin protomes. Her neck and décolletage are adorned with diamonds, a pearl necklace with pendants, a heavy garland, a row of pine cones and button-shaped objects, and a row of berry-like clusters. On her midriff are three rows of egg-shaped objects whose identification is controversial (possibly bull testicles) and she bears a lion on each forearm. She wears a belt depicting bees, rosettes, and serpent-tailed sea creatures and a kind of apron inset with square panels depicting winged sphinxes, lion-griffins, Rankenfrauen (female deities whose torsos emerge from leaves or calyxes), does, bees, equines, lionesses, bulls, and rosettes (Steskal 2010: 205–206; cf. Fleischer 1973, 46–136; Steskal 2008). This statue of the Ephesian Artemis displays a mutually entangled assemblage of living beings (animals and plants), divine beings, mythical hybrid beings, and non-living beings (monuments and minerals): a vibrant microcosm of the Roman world. For us, the ‘Great Artemis’ and her entanglements are ‘good to think with’ in a volume on posthumanism and Roman archaeology. We will return to her throughout this introduction.

Our volume originated in a session held at the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference (TRAC) 2016 (La Sapienza, Rome) entitled Beyond the Romans: What can Posthumanism do for Classical Studies?, co-organised by Irene Selsvold and Linnea Åshede. The aim of the session was to explore the possibilities offered by posthuman theoretical perspectives for the development of Roman archaeology and Roman studies, both in relation to how we approach the Roman world and to our own positions as researchers. Our experience from the panel was that posthumanism offers valuable perspectives on Roman myth, art, and material culture, displacing and complicating notions of human exceptionalism and individualist subjectivity. We found these perspectives to be particularly relevant for Roman mythology and religion, with its emphasis on metamorphoses, hybrid creatures, and encounters between actors that are human, divine, monstrous, or a mix thereof. Roman religion is rife with animated landscapes and sacred groves, the oracular capacity of ‘inanimate’ objects and liquid boundaries between images of gods and the gods themselves. Our panel contributors engaged with themes as diverse as Priapic statues, Roman attitudes towards the Galli, posthuman emperors, and the agency of epigraphic funerary markers. In our volume, we take up a few of these and other case studies to a) explore the potential and utility of posthuman theoretical perspectives for Roman archaeology, to b) de-centre the human subject in Roman archaeology, and to c) think through the entanglement, interactions, and relations of humans with other living and non-living beings in the Roman world, as well as the ethical implications thereof.

In this introduction, we begin with an explanatory outline of posthumanism in order to provide a clear theoretical framework for our volume. We then map the state of scholarship on posthuman perspectives in archaeology and the study of the ancient world, the aims of the volume, and the outline of our chapters. As we will discuss, the use of posthuman perspectives in archaeology is well established but the use of these perspectives for the study of the ancient world has just begun. Our volume offers a new encounter between Roman archaeology and posthumanism.

TRAC has long been a leading forum for the exploration of new theoretical perspectives in Roman archaeology. The TRAC Themes in Roman Archaeology series offers a rich venue for such exploration and we are delighted to be its third entry. We would like to thank the former and current TRAC Standing Committee, particularly Katherine A. Crawford, Lisa Lodwick, Matthew Mandich, and Sarah Scoppie, as well as Thomas J. Derrick for their support and numerous efforts on our behalf. Especial thanks go to Linnea Åshede for her vital role in the inception and development of this project, to Sabine Ladstätter and the Austrian Archaeological Institute (ÖAI) for their provision of our cover image of the ‘Great Artemis’, and to Francesca Ferrando for generously agreeing to write our foreword.

Posthumanism

‘Posthumanism’ is an umbrella term applied to a multiplicity of theoretical perspectives that critique humanism, de-centre the human subject, reconsider the boundaries and relations among humans and the natural world, and frame the human as ‘a non-fixed and mutable condition’ (Ferrando 2013: 27; cf. Miah 2008; Nayar 2014: 15–22; Bolter 2016: 1). Such posthuman theoretical perspectives also consider the agency of ‘non-humans’, e.g., living and non-living beings, landscapes, climate, and ideas, their entanglement, interactions, and relations with humans, and the situated nature of research. Fundamentally, these perspectives reject aspects of Western humanism, particularly anthropocentric, androcentric, and universalising assumptions, dualism, speciesism, transcendence, and the sovereign human subject (Miah 2008: 82–83; Ferrando 2012: 10–11; 2013: 29; Braidotti 2013: 56, 132; 2016: 23; Nayar 2014: 15–16, 19; Bolter 2016: 1). Many claim relational epistemologies and ontologies (sometimes termed ‘flat ontologies’) that are ‘not anthropocentric and therefore not centred in Cartesian dualism’ (Bolter 2016: 1), are grounded in a ‘philosophical critique of the Western Humanist ideal of “Man” as the universal measure of all things’ (Braidotti 2019a: 339), and focus on immanence (being within the world) (Ferrando 2012: 11; 2013: 29; Braidotti 2013: 56, 132; 2016: 23). Such epistemologies and ontologies are ostensibly divorced from human exceptionalism, the humanist assumption that ‘the proper study of man is man’ (Bolter 2016: 1), and the hierarchies that sustain ‘the primacy of humans over non-human animals’ and ‘sexist, racist, classist, homophobic, and ethnocentric assumptions’ (Ferrando 2013: 28). Posthuman theoretical perspectives are prominent in the humanities and social sciences, particularly in communication studies, cultural studies, feminist studies, literary criticism, philosophy, science and technology studies, and theoretical sociology (Ferrando 2013; Bolter 2016). A brief genealogy of posthumanism and an outline of these perspectives follow.

The terms ‘posthuman’ and ‘posthumanism’ were conceived by the postmodern theorist Ihab Hassan in his foundational article Prometheus as Performer: Towards a Posthumanist Culture? (1977). Using the titan Prometheus as an exemplum, Hassan challenged humanism and the human subject, and demanded a reconsideration of the relation of humans to and with other living and non-living beings. Drawing on antihumanist elements in Claude Lévi-Strauss’ A World on the Wane (1961), Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1970), and other works, Hassan critiqued the humanist ‘image of us, shaped as much by Descartes, say, as by Thomas More or Erasmus or Montaigne’ and called for ‘the annihilation of that hard Cartesian ego or consciousness, which distinguished itself from the world by turning the world into an object’ (Hassan 1977: 845). He proposed a ‘re-vision of human destiny […] in a vast evolutionary scheme’ and charged posthuman philosophers with the task of addressing ‘the complex issue of artificial intelligence’ (Hassan 1977: 845). For Hassan, Prometheus was a kind of posthuman subject, a figure that went beyond humanist divisions and dichotomies such as ‘the One and the Many, Cosmos and Culture, the Universal and the Concrete’ and allowed for the entanglement of ‘Imagination and Science, Myth and Technology, Earth and Sky’, that is, he (Prometheus) was a fundamentally relational being who offered ‘a key to posthumanism’ (Hassan 1977: 838). Essentially, posthumanism began with an allusion to an entangled and relational being in Greek mythology. Hassan’s critiques and core ideas laid the groundwork for the development of posthuman theoretical perspectives thereafter (Ferrando 2013: 26 n. 1; Bolter 2016: 1).

Beyond Hassan, posthuman scholars have been influenced by poststructuralist and postmodernist theorists, particularly Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Félix Guattari, Fredric Jameson, Bruno Latour, Jean-François Lyotard, and Paul de Man (Wolfe 2010: xi–xxxiv, esp. xii, xv, xx; Ferrando 2013; Bolter 2016: 2–4), whose theories critiqued and subverted, inter alia, ‘the [modernist] assumptions of universally applicable aesthetics and universally valid epistemology’, structuralist analyses of ‘language, literature, and culture’, ‘master narratives’, and the perceived ‘totalising practices and rhetorics of the modern era’ (Bolter 2016: 2). The antihumanism of Michel Foucault has particularly influenced posthuman scholars, as his ‘deconstruction of the notion of the human’ and the ‘death of Man’ inform many posthuman enquiries (Ferrando 2013: 31–32). However, posthumanism is not antihumanism per se, as humans, human concerns, and human rights are not excluded from posthuman enquiries (Ferrando 2012: 20; Braidotti 2013: 23). Such poststructuralist and postmodernist critiques and subversions inform posthuman theoretical perspectives.

Prominent theoretical perspectives often identified as posthuman are ‘critical posthumanism’ (posthuman critical theory), ‘cultural posthumanism’, and ‘philosophical posthumanism’ (posthuman enquiries emerging from the fields of literary criticism, cultural studies, and philosophy), ‘transhumanism’ (the study of human enhancement through science and technology), and ‘new materialisms’ (the study of matter and materialisation in the field of feminist studies) (Ferrando 2013; cf. slightly different classifications in Braidotti 2013: 38; Nayar 2014: 15–22). Critical posthumanism, cultural posthumanism, philosophical posthumanism, and new materialisms are characterised by post-anthropocentric, post-dualistic, post-exclusivist, and relational epistemologies and ontologies (Ferrando 2013: 27, 30; Braidotti 2016: 13, 23–27). In general, these perspectives are also characterised by relational ethics, that is, ethics that value ‘cross-species, transversal alliances with the productive and immanent force of […] non-human life’ (Braidotti 2016: 23) and ones that aim ‘at enacting sustainable modes of relation with multiple human and nonhuman others that enhances one’s ability to renew and expand the boundaries of what transversal and non-unitary subjects can become’ (Braidotti 2016: 26; cf. MacCormack 2012). In other words, human relations with others, and the ethical implications thereof, lie at the heart of these posthuman perspectives. New materialist perspectives have a particular focus on developing research methodologies ‘for the non-dualistic study of the world’ and challenging the perceived reductivism of dualisms such as ‘matter-meaning, body-mind and nature-culture’ (Van der Tuin 2019: 277–279; cf. Ferrando 2013: 30–31). These perspectives developed in response to a perceived inattention to matter and materiality in ‘the linguistic turn, the semiotic turn, the interpretative turn, [and] the cultural turn’ (Barad 2003: 801), that is, ‘the representationalist and constructivist radicalisations of late postmodernity, which somehow lost track of the material realm’ (Ferrando 2013: 30). For new materialists, there is no division between ‘language and matter’, for ‘biology is culturally mediated as much as culture is materialistically constructed’ and matter is ‘an ongoing process of materialisation’ (Ferrando 2013: 31; cf. Barad 2003; Coole and Frost 2010; Van der Tuin 2019). While these four overlapping perspectives emerged from different fields and have different genealogies and foci, they share the same impetus to ‘understand what has been omitted from an anthropocentric worldview’ (Miah 2008: 72; cf. Ferrando 2013: 32). By contrast, transhumanism is a kind of ‘ultra-humanism’ that narrowly focuses on human enhancement and is characterised by a distinctly anthropocentric epistemology, what Cary Wolfe has termed ‘an intensification of humanism’ (Wolfe 2010: xv; emphasis in original). As such, some posthuman scholars argue that transhumanism should not be considered a form of posthumanism (Wolfe 2010: xv; Ferrando 2012: 11; 2013: 27–28; Nayar 2014: 16–18). We concur with Wolfe’s claim that ‘posthumanism is the opposite of transhumanism’ (Wolfe 2010: xv; emphasis in original) and, as such, will not focus on transhuman perspectives in this volume. Prominent scholars of posthumanism and new materialisms whose theories have influenced this volume inc...