1

Disability in the 21st Century

Seeking a Future of Equity and Full Participation

Michael Wehmeyer

This book’s purpose is to address contemporary issues in supporting people with severe disabilities to live rich, full, and high-quality lives in their communities. It will be difficult to achieve the vision established in this book until there is a fundamental change in the way in which disability itself is understood. A new and different way to understand disability in the 21st century does exist. This chapter describes that new paradigm and discusses the implications of its adoption for a future of equity and full participation.

HISTORICAL UNDERSTANDINGS OF DISABILITY

I coedited a book titled Mental Retardation in the 21st Century (Wehmeyer & Patton, 2000). Use of the stigmatizing term mental retardation has been discontinued for reasons subsequently discussed. I coauthored a chapter in that text with Hank Bersani, Jr., and Raymond Gagne, two leaders of the self-advocacy movement, that characterized the current era as representing the third wave of the disability movement. Our formulations were guided by issues pertaining to civil rights and social justice emerging through the field’s growing acceptance of the self-advocacy movement and focus on self-determination. Significant progress in elaborating better ways of understanding disability has provided a theoretical and scientific foundation to bolster the philosophical and moral issues that propelled our proposal of a new wave of the disability movement. The oft-cited adage that “what is past is prologue” is apropos in considering how to ensure a future of equity and full participation.

The First Wave of the Disability Movement: The Professional Era

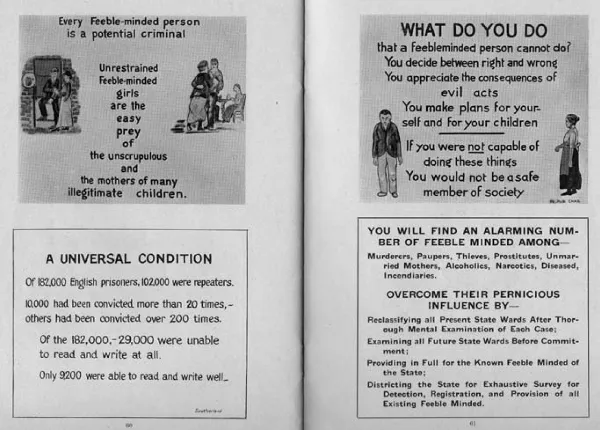

Professionals dominated the first wave of the disability movement, which spanned through the latter half of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. At the height of this first wave, professionals defined the issues and created the then new discipline of disability as a subdiscipline within the fields of medicine, psychology, and education (Dybwad & Bersani, 1996). These professionals made decisions on their own or in consultation with one another. Parents and the public assumed that these professionals knew what was best because of their education and social status. Emphasis was on diagnosing and determining who would benefit from treatment. The images associated with disability were often universally negative. People with disabilities were stereotyped as menaces to society or responsible for many societal problems (see Figure 1.1) (Trent, 1994; Wehmeyer, 2013).

How disability itself was understood during this era was an extension of the medical model adopted by these early professionals. Disability historically was understood as an extension of a medical model that conceived health as an interiorized state of functioning and health problems as an individual pathology; that is, as a problem within the person. Disability within such a context was understood to be medical in nature and a characteristic of a person, as residing with that person. The person was viewed as broken in some way. The language of the professions that emerged to support people with disabilities reflects that conceptualization; people with disabilities were described as diseased, pathological, atypical, or aberrant, depending on the profession (Wehmeyer et al., 2008).

The way in which disability is understood drives how people with disabilities are treated in both the sense of the nature and structure of services and supports provided to them and in the sense of how others, including the public, respond to them. The earliest efforts on behalf of people with disabilities were habilitative in nature and driven by tenets of social justice and social welfare. Thus, schools were established beginning in the 1830s and into the 1870s to educate children who were deaf or blind or who had an intellectual disability. People with severe disabilities were not included in these early efforts, however. For example, early schools for children with intellectual disability included only people who had limited support needs. Such efforts, however, transmogrified over time from habilitative in nature and intended to benefit the person to serving to isolate and segregate people with disabilities from society, eventually for the purposes of protecting society (Smith & Wehmeyer, 2012).

The professionals that built this system were not interested in the rights of people whom they called “retardates” or “mentally deficient.” People with severe disabilities were seen as menaces to society; threats to “racial hygiene”; and links to crime, poverty, promiscuity, and the decline of civilization by the first decades of the 20th century. They were seen as subhuman (“a vegetable”) or as objects to be feared and dreaded by these professionals and society at large. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1927 that involuntary sterilization of people who were deemed to be feebleminded was constitutional, resulting in the forced sterilization of an estimated 50,000 people with intellectual and developmental disabilities by the 1970s (Smith & Wehmeyer, 2012).

More than 275,000 Americans, including most people with severe disabilities, lived in institutions that had become massive warehouses by the late 1960s. The Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, built to house 4,000 people, had an institution census of more than 6,000 inmates by the mid-1960s. After a tour of Willowbrook in 1965, a visibly distraught Senator Robert Kennedy told reporters,

I think—particularly at Willowbrook—that we have a situation that borders on a snake pit; the children live in filth; many of our fellow citizens are suffering tremendously because of lack of attention, lack of imagination, lack of adequate manpower. (Smith & Wehmeyer, 2012, p. 176)

Disability scholar Burton Blatt was propelled by Kennedy’s pronouncements and arranged to tour four institutions in the northeast, none of which were named but one of which was almost certainly Willowbrook, and brought with him photographer Fred Kaplan, who surreptitiously snapped photographs of the horrific conditions in the facilities. The resulting photo essay showed the stark black-and-white photographs of naked and apparently starving “inmates” with severe disabilities and rows of iron beds with children confined to them, juxtaposed with poetry verses and essays selected by Blatt. “There is hell on earth,” began Christmas in Purgatory, “and in America there is a special inferno. We were visitors there during Christmas, 1965” (Blatt & Kaplan, 1969, p. 1).

The Second Wave of the Disability Movement: The Parent Era

The parent era was the second wave of the disability movement and occurred during the middle of the 20th century. Advances in science and medicine greatly increased the life expectancy of people with disabilities. A growing worldwide emphasis on rehabilitation and training emerged, catapulted forward by the large number of veterans disabled in World War II. Successes in developing vaccines for diseases such as polio and tuberculosis gave hope to greater cures for disabling conditions. The earlier stereotypes of disability were replaced with more humane ones, though this change was still problematic. People with disabilities were viewed as objects to be fixed, cured, rehabilitated, and, at the same time, pitied. They were viewed as victims of their disabling condition, worthy of charity. Shapiro described this when discussing the emergence of the poster child as a fundraising tool:

The poster child is a surefire tug at our hearts. The children picked to represent charity fund-raising drives are brave, determined, and inspirations, the most innocent victims of the cruelest whims of life and health. Yet they smile through their unlucky fates. No other symbol of disability is more beloved by Americans than the cute and courageous poster child. (1993, p. 12)

People with severe disabilities were viewed as holy innocents within this stereotype (e.g., special messengers, children of God) and, thus, incapable of sin and not responsible for their own actions. People with severe disabilities came also to be perceived as eternal children, partially based on the prevalent use of mental age calculated from intelligence scores. Although no longer feared and blamed for all social ills, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities were perceived as children that needed protection, pity, and care.

The advances in science and changes in societal perceptions emboldened parents to demand to participate in decisions that affected their children and to reject the pessimistic forecasts of professionals as well as the treatment regimens associated with those forecasts, most notably institutionalization. Parents and family members began to advocate for services that would enable their children to remain at home, attend school, and live and work in their communities. Professionals slowly joined in the parent rebellion and recognized the importance of parents in the decision-making process. The movement eventually gained political clout and radically and unalterably changed the face of disability services during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s (Abeson & Davis, 2000).

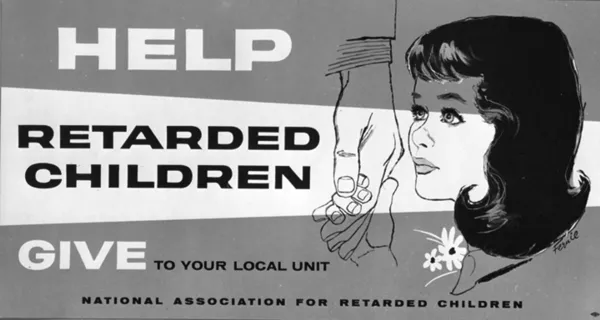

The parent era ushered in the community era. Inclusion in communities and schools became the focus. Deinstitutionalization, spearheaded by pioneers such as Burton Blatt and nurtured by the wide adoption of the Normalization Principle (Nirje, 1969) and the emergence of the independent living movement, resulted in the shift from large congregate settings to community-based, although still congregate, living and educational settings. Nevertheless, this second wave did not alter the understanding of disability. Disability was still seen as aberrant, atypical, or pathological; as residing outside the normative experience and as a characteristic, quality, or condition of the person. People with disabilities were seen as broken or diseased. Terms such as invalid, cripple, and handicapped, which were prevalent during this era, spoke to this understanding. People with disabilities were treated as victims to be pitied and helped (see Figure 1.2). Beyond the hope for a cure engendered by scientific advances, not much else changed about the way disability was understood.

The Third Wave of the Disability Movement: The Self-Advocacy Era

The self-advocacy or self-determination movement emerged in the 1970s and 1980s (Wehmeyer, Bersani, & Gagne, 2000). Parents and family members told professionals during the second wave of the disability movement that they were the consumers of services and they were the ones who speak for their children. This emphasis changed as their children aged and the movement matured. Parents, family members, and professionals began to recognize that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities could speak for themselves (Abeson & Davies, 2000). The self-advocacy or self-determination movement emerged as people with disabilities, increasingly referred to as self-advocates, began to claim their own voices. This movement emphasized empowerment, self-determination, and community inclusion.

Several factors contributed to the emergence of the third wave. The progress achieved by parents in establishing community-based programs (e.g., education, community living, employment settings) created a climate that led to further protections and higher expectations. Several other movements also contributed to the emergence of the third wave.

The first movement was adopting the Normalization Principle as an organizing basis for service delivery in the 1970s. Bengt Nirje explained that the Normalization Principle had its basis in “Scandanavian experiences from the field” (1969, p. 180) and emerged, in essence, from a Swedish law on mental retardation passed in 1968. In its original conceptualization, the Normalization Principle provided guidance for creating services that “let the mentally retarded obtain an existence as close to the normal as possible” (p. 181). Nirje stated, “As I see it, the normalization principle means making available to the mentally retarded patterns and conditions of everyday life which are as close as possible to the norms and patterns of the mainstream of society” (p. 181). Nirje identified eight facets and implications of the Normalization Principle.

1. Normalization means a normal rhythm of day;

2. Normalization implies a normal routine of life;

3. Normalization means to experience the normal rhythm of the year;

4. Normalization means the opportunity to undergo normal developmental experiences of the life cycle;

5. Normalization means that the choices, wishes and desires [of the mentally retarded themselves] have to be taken into consideration as nearly as possible, and respected;

6. Normalization also means living in a bisexual world;

7. Normalization means normal economic standards [for the mentally retarded];

8. Normalization means that the standards of the physical facility should be the same as those regularly applied in society to the same kind of facilities for ordinary citizens. (1969, pp. 181–182)

Scheerenberger noted that “at this stage in its development, the normalization principle basically reflected a lifestyle, one diametrically opposed to many prevailing institutional practices” (1987, p. 117) and suggested that “no single categorical principle has ever had a greater impact on services [for people with mental retardation] than that of normalization” (p. 117).

Second, the independent living and disability rights movements were critical to the emergence of the new wave of the disability movement. The independent living movement began in the 1960s and was strongly influenced by the social and political consciousness of other civil rights movements occurring in the United States at that time (Ward, 1996). This civil rights perspective and the recognition of the lack of power held by and value held for people with disabilities at that time led many people with disabilities to equa...