![]()

SECTION II

The Co-Design Model for Collaborative Instruction

![]()

CHAPTER 3

Explanation of the Model

Collaboration is a term that is often mentioned as a positive initiative within schools. Many education professionals speak of the favorable impact that collaboration has on the planning and delivery of instruction. If educators want schools to improve and students to reap the greatest benefits from instruction, it is essential that they seek input from fellow teachers from whom they can learn. Collaboration involves creating communities of professionals who work together to share ideas, solve problems, and promote positive changes that benefit students. Although there is no one right way to collaborate, effective collaboration requires mutual respect and trust, open communication, and the sharing of work to achieve a common goal.

When I was working as a building principal, I attempted to create an atmosphere in which teacher collaboration would drive the planning and instruction of school programs. Lesson planning, data analysis, and co-teaching were all addressed in a collaborative environment. Like many other administrators, I firmly believed the old adage that many heads are better than one. I felt that I was on solid ground in my effort to promote collaboration among the staff, even though the benefits were primarily of the “feel-good” variety. The staff enjoyed the opportunity to share ideas and materials, and the mutual planning time made the teachers happy. However, it was not until I began my doctoral work that I truly realized the impact that collaboration can have on teaching and learning.

I conducted a qualitative study of a school that had implemented a collaborative structure in 2003. After years of working in isolation in three separate buildings, the teachers were brought together in one building where their grade level could meet daily. This meeting time was used to establish program goals, plan instructional activities, share resources, and discuss student progress. The results of this research revealed six indisputable benefits from the efforts of collaboration:

1. One hundred percent of the study participants stated that their teaching had improved since the collaboration model was established. The teachers felt that the model gave them more support to try new ideas and fine-tune their activities to meet the students’ needs.

2. Teachers agreed that the collaborative atmosphere expanded their repertoire of resources and promoted the use of recommended practices for instruction.

3. Continuity improved within the curriculum and instruction. The staff commented that they were all on the same page with regard to instructional planning and delivery.

4. The instructional focus shifted from the teachers to the children. The teachers acknowledged that their conversations began to focus more on student learning and on teaching to the students’ learning styles.

5. Academic rigor increased dramatically as the teachers developed core competencies that they expected their students to achieve, as well as formative and summative assessments to evaluate student achievement.

6. The collaborative structure gave the teachers a greater sense of accountability. They felt more responsible for ensuring student success and more accountable to their peers for meeting school goals.

Clearly, the concept of collaborative instruction is not merely a simple, feel-good school initiative. In fact, an effective collaborative environment can reap benefits for both students and teachers that far exceed expectations.

By Wesley Shipley, Ed.D., Superintendent, Shaler Area School District serving Shaler Township, Millvale, Etna, and Reserve Township, Pennsylvania

Collaborative instruction is an undeniable ingredient for successful education (Friend, 2011; Villa, Thousand, & Nevin, 2004; Werts, Culatta, & Tompkins, 2007). Gargiulo (2006) reports that the use of collaborative practices in schools is increasing. At some point in their teaching careers, it is likely that most educators will be expected to collaborate and co-instruct with other professionals. The Co-Design Model for collaborative instruction (Barger-Anderson, Isherwood, & Merhaut, 2010; Hoover, Barger-Anderson, Isherwood, & Merhaut, 2010) provides a means for support and professional development, along with strategies for implementation, to ensure that collaborative and inclusive efforts meet success.

Shade and Stewart (2001) stated that general educators in inclusive classrooms often find it difficult to select proper instructional strategies for students with disabilities. These researchers also found that lack of administrative support and planning time is a common problem. Often, schools implement inclusive practices expeditiously without providing proper training and support to the general education teachers (Hammond & Ingalls, 2003). The goal of collaboration in the educational setting is to achieve shared accountability for all students in an inclusive environment. Using the Co-Design Model as a framework for developing and implementing collaborative and inclusive initiatives can assist educators and administrators in accomplishing this goal.

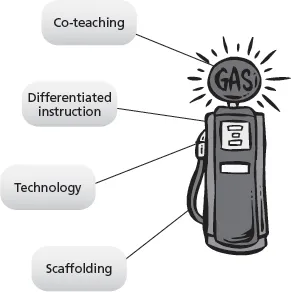

The Co-Design Model is composed of nine elements. These elements are essential for realizing the model's maximum potential. The model also endorses four pathways that educators can use on a day-to-day basis to implement strategies and tactics within the collaborative environment. These pathways are research-based recommended practices that have proven successful in promoting achievement for all levels of learners. There are two analogies that are helpful to understanding how the elements and the pathways work together. The first is to think of the model as a brick building. The elements serve as the bricks and the pathways are the mortar used to hold the bricks together. In other words, the pathways are used to support the structure. The other analogy is that of a vehicle, as illustrated in Figure 3.1. The automobile represents the elements, and the pathways act as the gasoline that enables the car to get from Point A (i.e., the students’ initial level of knowledge) to Point B (meeting new learning goals and objectives). In either example, the key to success is understanding how to combine the implementation of the elements and pathways to work synergistically as one model.

These nine elements may appear separately in many classrooms. But when all of the elements are implemented simultaneously, they form the Co-Design Model. It is difficult to say whether one element is more important than another. Therefore, the Co-Design Model stresses that all nine elements must be implemented and addressed; if one or more elements are left out, the participants risk compromising their ability to reach the highest level of collaborative success.

Figure 3.1. A visual analogy of the nine elements and four pathways of the Co-Design Model. (Source: Barger-Anderson, Isherwood, Merhaut, and Hoover, 2010.)

The Co-Design Model is defined as the interaction of professionals engaged in collaborative efforts who share in the obligatory responsibilities for the administration of instructional and noninstructional duties and tasks within an educational setting (Barger-Anderson et al., 2010). This means that the model takes the concept of collaboration in inclusive classrooms beyond just the implementation of common co-teaching models by promoting collaboration that extends beyond the instructional aspects of planning and executing lessons. The model emphasizes the need for reliable and effective collaborative approaches to classroom management, parental contacts, grading of homework, assessments, adaptations, and other components necessary to successfully operate a classroom (Barger-Anderson et al., 2010).

ELEMENTS OF THE CO-DESIGN MODEL

The nine elements of the Co-Design Model are

1. Leadership

2. Assembly of site

3. Curriculum knowledge

4. Co-instruction

5. Classroom management

6. Adaptations, accommodations, and modifications

7. Assessment

8. Personality types

9. Co-design time

Leadership

The element of leadership (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4) encompasses several of the other elements of the Co-Design Model as well as some of the pathways for implementation. For this reason, it is positioned as the first of the nine elements. Some advocates of the Co-Design Model argue that no educational initiative of any kind can succeed without the support of effective leadership by school and district administrators. The leadership element emphasizes the crucial need for administration to ensure sustainability, continued reinforcement, and a long-term commitment throughout the collaborative initiative.

In the Co-Design Model, the leadership element addresses issues such as providing the collaborative partners with common planning time and opportunities for professional development. It also addresses teacher evaluations. Specifically, the leadership element advocates enhancing teachers’ professional growth via classroom observations by administrators and outside consultants, peer observations, and feedback on specific lessons. This support includes providing time for the administrators and consultants to conduct preobservation and postobservation conferences with the teachers, both individually and with their collaborative partners.

Gargiulo (2006) found that few general educators believe they have the basic foundation of knowledge needed to address the increasingly diverse needs of all learners in inclusive classrooms. Santoli, Sachs, Romey, and McClung (2008) accentuate that administrative support is necessary for the success of inclusive and collaborative education. Their research demonstrates that even though most teachers at the middle level feel that they receive sufficient support in most other areas, they do not feel that the administrative team allots enough planning time between the general educator and the collaborative partner(s).

Assembly of Site

Assembly of site (discussed in Chapter 5) refers to the organization of physical components within a shared educational venue, along with the promotion of collaborative practices via site management (Barger-Anderson et al., 2010). This element of the Co-Design Model addresses issues such as location of the teaching site, the arrangement of furniture and other items within the shared space, and promoting communication between the collaborative partners to help them plan these logistics. The physical setting for collaborative instruction may be a classroom, an auditorium, two classrooms split between two groups of students, or any other configuration. Even though no two schools are physically the same, lack of adequate space seems to be a common problem.

Gately and Gately (2001) and Villa et al. (2004) agree that the physical arrangement of a shared teaching site needs to be discussed between the collaborative partners. The assembly of site element also helps ensure that the physical setup creates a truly collaborative environment that promotes parity between the partners. Parity is achieved when all partners in a collaborative relationship feel a sense of value and contribution to the educational experience. Parity does not mean that all responsibilities are divided equally; rather, it recognizes that education professionals have individual strengths and differing areas of expertise (Friend, 2011; Villa et al., 2004).

The physical assembly of the classroom or site of instruction should send a clear message that the setting is a shared environment. For example, this may include providing two teacher desks and displaying the names and pictures of both teachers in the room.

Curriculum Knowledge

Curriculum knowledge (see Chapter 6) refers to the different backgrounds, knowledge, and skill sets that each teacher brings to the collaborative classroom. The general education teachers are trained and certified within their own content disciplines. The special educators are experts who are trained and certified in the discipline of special education. In many cases, the special educators may be certified or deemed highly qualified to teach in at least one additional content area. The Co-Design Model's curriculum knowledge element addresses issues such as resolving concerns about one co-teacher's possible lack of curriculum knowledge, providing the time required for teachers to learn curriculum, and ensuring that co-teachers respect each other's strengths, disciplines, and skills. The success of a collaborative teaching relationship may hinge on the level of content and subject area assigned. The content knowledge and skill sets of each partner may differ greatly depending on the class assignment (Friend & Hurley-Chamberlain, n.d.; Gately & Gately, 2001).

Because, according to the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2011), the number of students with disabilities who receive their education in inclusive environments is increasing, curriculum knowledge is an ...