![]()

Chapter 1

BEGINNINGS

And God said, Let there be light . . .

—Genesis 1:3

PRECISELY AT THE STROKE OF MIDNIGHT, as the clock turned from July 9, 1856, to July 10, 1856, Nikola Tesla was born in the village of Smiljan, in the mountainous Austrian province of Lika. (Lika is a historical region of Croatia and is located today in the Republic of Croatia. At the time of Tesla's birth, however, it was part of the Austria-Hungarian Empire). As both lore and his own autobiographical writings tell us, Tesla came into being amid a raging lightning storm. Whether or not he was possessed with God's prophecy, it was indeed his destiny to light up the world. And while he is credited with achieving just such a mythical feat, he was first and foremost a man of nature, scientific inquiry, and prodigious invention. A view into his early years, inventive process, phobias, reasoning powers, reclusiveness, dreams, and survival tactics comes to us through his autobiography, My Inventions (1919).

Homeland

The world of Smiljan has a long, volatile history, caught up in what we now know as the warring Balkan states. Lika and other regions in Croatia were under Austria-Hungarian rule beginning in the mid-1800s, while neighboring Bosnia was under Turkish control. Both Croatia and Bosnia fought for years to gain independence from their ruling powers. Once they obtained their freedom—and right up to the present day—the diverse factions in Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, and Slovenia continued to fight among themselves and their neighboring states. Following World War II, Croatia became one of the six constituent republics of the Yugoslav socialist federation. Once again, Croatia fought for its freedom and engaged in bitter fighting with Serbia. The complex of shifting borders across this region of the world gave rise to the word balkanization.

It was in this geopolitical context and amid these natural surroundings that Nikola Tesla spent his childhood. Smiljan lay across the western edge of the Austria-Hungarian Empire's military frontier. Many of its men were conscripted to go off and fight wars, while others chose a religious path. Meanwhile, the female residents back home eked out a living on hardscrabble farms, often plagued by famine. By the time of Tesla's birth, a decline in Turkey's control of the surrounding area gave rise to civilian administration.

Although Tesla was born in Croatia, his parents were of Serbian descent. Milutin, his father (1819–1879), was a minister who graduated at the top of his class. He had no desire to pursue a military career, as so many of the men in his family had done. Tesla's mother, Djuka (translated as Georgina) Mandic (1822–1892), was the daughter of a priest. Her family lineage included many who chose a career in the clergy. Shortly after their marriage in 1847, Milutin was transferred to a parish in Senj and later to one in Smiljan.

Milutin was a pastor, writer, and poet with an extensive library on wide-ranging subjects. He strongly desired independence from the Austrians and Turks, as well as everlasting peace. Milutin spoke many languages, was adept at mathematics, and trained his sons to perform calculations in their heads as well as feats of memory.

Although Djuka could not read, she committed to memory long passages from the Bible. She was a dutiful homemaker, who in her own right was an inventor of many household items. Working from sunup to late in the evening, she would run the farm and household. Her sewing abilities were renowned, aided by looms she devised herself. To help prepare meals, she invented churns and labor-saving kitchen devices for their small, isolated farm. Both parents shared a sense of the spiritual and viewed life beyond the rigors of farming. Their quest to improve the human condition was not lost on the young Tesla. The fourth of five children, he was closest to his mother and shared her work ethic, as well as her sense of invention for tools that would better the world.

Early Visions and Scientific Intuition

“Our first endeavors are purely instinctive,” Tesla would write in his autobiography, “prompting of an imagination vivid and undisciplined. As we grow older, reason asserts itself and we become more and more systematic and designing. But those early impulses, though not immediately productive, are of the greatest moment and may shape our very destinies.”

A number of events in Tesla's childhood life were to have a marked effect on his future as an inventor, dreamer, strategist, and communicator in different realms. Young Nikola spent much of this early life amid birds, chickens, geese, sheep, horses, and cats. It was an extensive immersion in the natural wonders around him. He went to great lengths to talk to the animals, especially his favorite cat, Mačak.

Stroking Mačak on a cold, dry winter night, Nikola observed sparks of light emanating from the animal's backside. His father explained that this was static electricity, much like that seen during lightning storms. It was the same kind of electricity one was able to produce by rubbing one's feet on a rug, resulting in a spark when touching another person. Tesla was fascinated. He reasoned that the jolt of electricity was a kind of power or energy, and he wondered: How could he produce greater quantities of electricity? What would he have to do increase the output of these electrical forces? Then, how could he utilize electricity to power machinery? As he recalled at the age of 80, these were all grand ideas circulating in his head at an early age.

I cannot exaggerate the effect of this marvelous night on my childish imagination. Day after day I have asked myself “what is electricity?” and found no answer. I still ask the same question, unable to answer it. Some pseudo-scientist, of whom there are only too many, may tell you that he can, but do not believe him. If any of them know what it is, I would also know, and my chances are better than any of them, for my laboratory work and practical experience are more extensive, and my life covers three generations of scientific research. (“A Story of Youth Told by Age”)

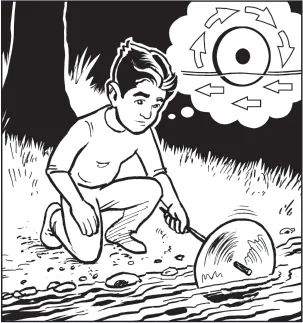

In addition to communing with the farm animals, Nikola was close to his elder brother Dane (b. 1848) and formed more distant relationships with his sisters, Angelina (b. 1850), Milka (b. 1852), and Marica (b. 1858). Much of his playtime was spent intermingling with nature, observing cause and effect. The forces of nature—such as the power of flowing water and wind—were very real to him. In particular, the impact of water current on floating objects took shape in his mind. How would he transform these myriad thoughts into reality and useful purposes? These were his seeds of invention. From a young age, he began formulating ideas for translating natural forces into the transmission of usable energy.

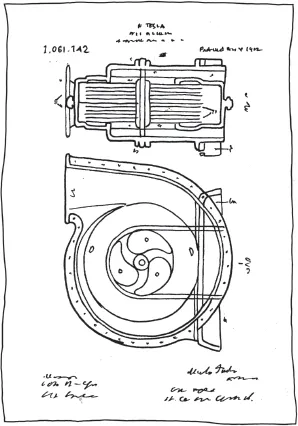

By observing how a flowing stream could propel a toy boat, for example, he began to formulate variations of the physical event. For a budding inventor, this was the magic “what if?” moment. Nikola theorized that the water's current would have the same effect on a wheel or disk, which would rotate if mounted on an axle hovering perpendicular above the flowing stream. A portion of the disk just below the axle would be immersed in the water and would spin in direct relationship to the current pushing against it. With that theory in mind, Nikola constructed just such an apparatus and noted the resultant effects. How his observations would figure in his future would require the test of time. For the moment, these were early hints of his thought process for the invention of a smooth-disk turbine (PATENT 1,061,142 – FLUID PROPULSION, filed October 21, 1909, and PATENT 1,061,206 – TURBINE, filed October 21, 1909).

Air flight was another concept that loomed large in the boy's mind, so much so that he took to leaping off the barn roof with umbrella in hand to ease his descent. He spentanumber of months in bed healing.

In addition to experimenting with physical phenomena, Tesla believed strongly that he possessed the ability to both communicate and predict events beyond the natural order of things. He was convinced that his sensory apparatus went beyond seeing and hearing the things right in front of him. He claimed that he could hear a small object dropped in another room or at a great distance, and that the sound of unseen objects at times became so deafening that it caused him intolerable headaches. On one occasion, he visualized the death of his cat Mačak. When later told the exact details of his pet's passing, the account confirmed precisely what he had seen in his mind.

Similarly, in thinking about a possible invention, Tesla would pose a series of questions to himself and work through the potential solutions. Ultimately, release would come in the form of what he regarded as complete clairvoyance for a practical invention. At other times, he imagined that he could reach right through the space in front of him and touch aspects of the image. If he saw something, he wondered, would it be possible to invent a device that could project the image as his eye saw it? Obsessively he grappled with these ideas. And though nothing came of many, they were the earmarks of the intense scientific inquiry that gripped Tesla from a very early age.

Another unique childhood invention came about through his observation of the forces of wind. Living on a farm, it would not be far-fetched to assume that he was able to observe the effects of a windmill in the threshing of grain. But, young Tesla wondered, what if there is not enough wind to turn the mill?

Melding what he learned from the water-driven spinning wheel, he devised a system of pulleys that attached a wheel to a model windmill. Then he tethered a collection of May flies (June bugs in North America) to the windmill's vanes. The frantic flapping of the bugs' wings set the wheel in motion. Nikola proudly showed off his invention to a boy in the neighborhood who proceeded to eat the bugs. The sight of him gobbling the bugs so disgusted Tesla that he vowed never to harm an animal again. And according to one biographer, he never repeated the experiment in the rest of his life.

Nikola eagerly moved on to other juvenile experiments. He would tinker endlessly with clocks, taking them apart but never succeeding in putting them back together. As military weapons caught the fancy of many a young boy, he constructed a popgun in which he utilized forced air-pressure to propel a wad of hemp. The result was a few shattered windows. In another flight of invention and imagination, he fashioned his own swords and waged war against an imaginary advancing army of cornstalks. Such adventures aroused the ire of his parents, but for Nikola they were the beginnings of his life-long search for what makes things work.

One particular image came to haunt him for the rest of his life. It occurred when he witnessed his brother Dane being thrown by their favorite horse. The resulting injuries led to his brother's death at the age of 12. The incident replayed itself in his mind, in stark detail, throughout Tesla's life. Dane's death was a cause of great anxiety and frequently distress. Tesla's fixations would lead to crippling headaches and mental breakdowns on numerous occasions. Often his memories would be accompanied by brilliant flashes of light inside his mind, as if war was being waged in his head.

Early Education and the Possibility of Advanced Power

Young Nikola Tesla had looked up to his brother. Dane's death in 1861 was a stunning blow not only to young Nikola; it proved devastating to their parents. No matter what Nikola did, he felt that he lost favor with his parents. His mother seemed t...