- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Linguistics For Beginners

About this book

Linguistics For Beginners is the first book to ever make the arcane labors of linguistics accessible to general readers. It begins with a lucid definition of language and proceeds to examine how it becomes the subject matter of linguistics. Key topics include the contrast between writing and speech, and elementary lessons in analyses ranging from simple sounds to entire sentences. Absurd fictions such as Eskimos having hundreds of words for snow are exploded, and the borderlands between linguistics and philosophy are investigated.

Linguistics For Beginners teaches concise lessons using wit and whimsy making for a memorable learning experience. The reader will learn about language acquisition, ancient languages, little-known languages, tonal and whistle languages, linguistic engineering, structuralism, language origins, the anthropological approach to linguistics, kinship semantics, color lexicons, geographical linguistics, and much more! Linguistics For Beginners is the key tool for linguistic students of any level.

Linguistics For Beginners teaches concise lessons using wit and whimsy making for a memorable learning experience. The reader will learn about language acquisition, ancient languages, little-known languages, tonal and whistle languages, linguistic engineering, structuralism, language origins, the anthropological approach to linguistics, kinship semantics, color lexicons, geographical linguistics, and much more! Linguistics For Beginners is the key tool for linguistic students of any level.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

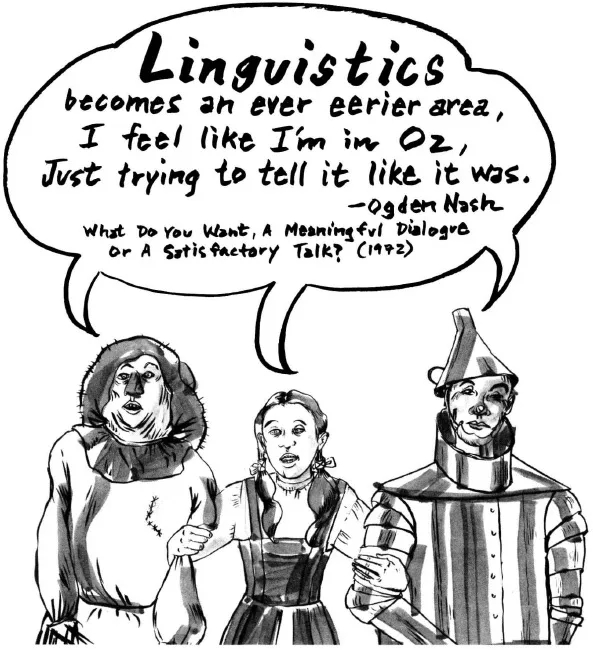

If you have already heard about linguistics or read something about the subject, and you share the feeling that Ogden Nash describes above, you′ve come to the right book. If you know nothing at all about the topic but have picked up this book out of sheer curiosity, so much the better. Read on, and take your first steps toward learning what linguists do for a living.

HOW LANGUAGES WORK

Lessons One and Two

Let’s start with these basics:

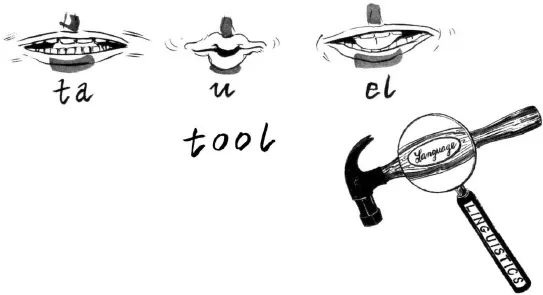

language is a tool;

linguistics is the analysis of language

linguistics is the analysis of language

Why say that language is a tool? Because like any of the things that we recognize as tools, from hammers to computers, it lets us do things that would otherwise be impossible or a lot harder to do (try to imagine driving nails without a hammer or compiling a city phone directory without the help of a computer).

Language is a tool for getting thoughts out of our brains and into our mouths and into other brains.

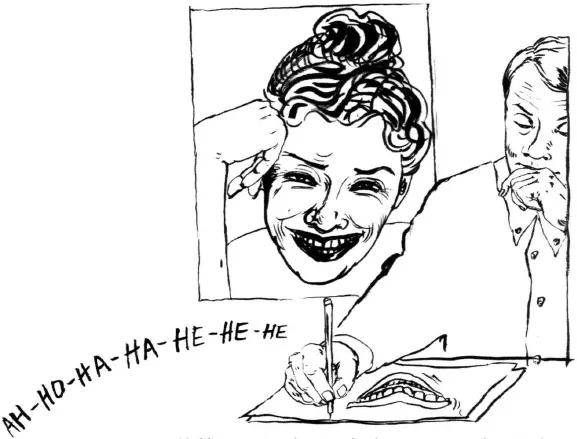

How else would we communicate? Sure, you can just let out a yell to warn of danger, or a groan to express pain, strain, or boredom, and a map or a sketch can give a lot of information. But try sketching this:

I’ll never forget her laugh.

Apart from “laugh,” the elements of this sentence are too abstract for a picture. They are ideas and concepts, expressible only when organized by and into a complex system: language.

Unlike most other tools, language can be used on itself, and that is exactly what happens in the study called linguistics. It is analysis of language, it is language about language.

Here’s another way to think about it: linguistics is to language what a mechanic’s manual is to a car. A linguist working on a language with analytical tools is not much different from a mechanic working on an engine with his socket wrenches. The shop manual is not a driver education handbook. and a book on linguistics does not teach you how to speak. It’s possible to be a competent mechanic without knowing how to drive a car and just as possible to be a linguist without being fluent in the language you are analyzing. (More about this below, where we meet three guys named Chomsky, Mithridates, and Fazah.)

What? No Words?

So far, we haven’t said a word about words, and we’re not defining linguistics as words about words. Why? Because linguistic analysis is not limited to words.

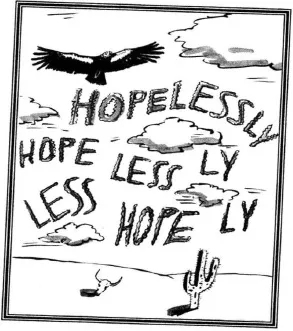

Linguistics goes below and above the word. It takes words apart (hopelessly=hope+less+ly) and examines how the parts go together (hope+less+ly but not less+hope+ly). It also looks at how words form groups (He is hopelessly lost but not Lost is hopelessly he).

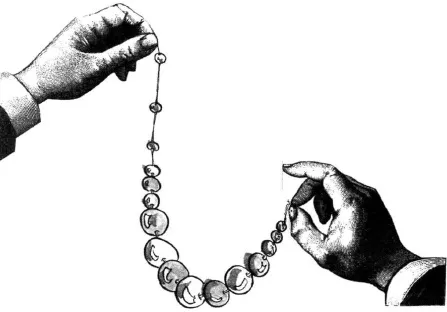

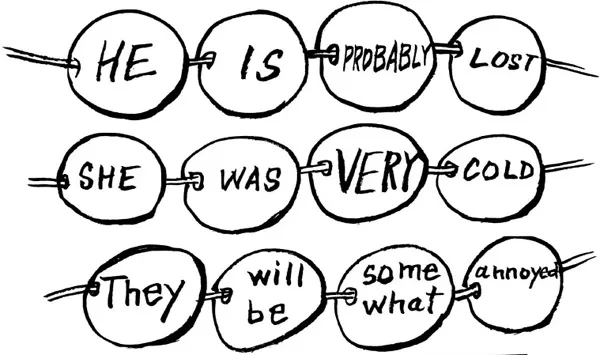

When a sentence makes sense, its words are linked like pearls on a string. What keeps the words together is a pattern. Many different sets of pearls could be put together on the same piece of string, and many different sets of words can hang together on the same pattern. The study of patterns for sentences is called syntax by linguists and grammar by the rest of the world. Let’ go back to our example: He is hopelessly lost.

This sentence has the same pattern (we could also say the same model or the same structure, and we will see later that structure especially is a favorite word among linguists) as the following:

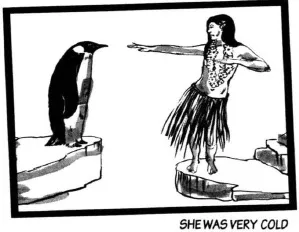

He is probably lost. She was very cold. They will be somewhat annoyed.

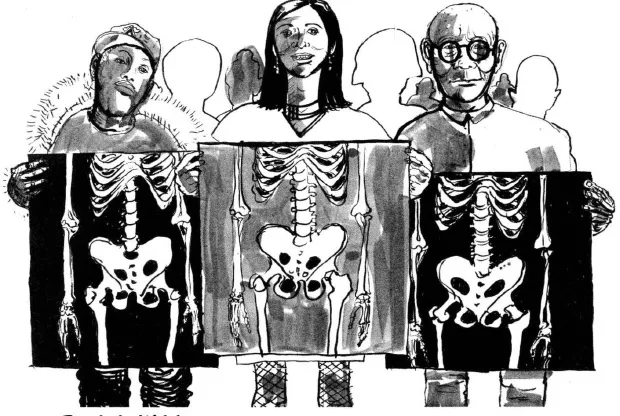

Linguists are a lot less interested in words than they are in how words combine with each other and in how bits and pieces combine to make up a word. The bits and pieces of spoken language turn out to be more interesting than those of written language, because there is more regularity, more system, more pattern, more structure (there’s that linguist’s word or choice again) in speech than in writing. Think of it this way: you can line up ten people who all look very different from each other, but if you line up their x-rays, their skeletons will look very similar. Linguists pay more attention to skeletons than to skin; they spend more time studying the sounds of speech and sound systems than words on the page.

Put it in Writing

But let’s not imagine that learning about writing is completely outside the important fundamentals of linguistics. We write English in what is called a phonetic alphabet. This means that the letters of the alphabet stand for sounds, the most basic elements of language that linguists study.

A phonetic alphabet is a medium, in the sense of an extension of our bodies. It turns the sounds of language that we produce with our lungs and tongues and teeth and lips into visual marks, whereas the sounds of language are an extension of the thoughts in our minds. Here we are back at the basic idea we started with: language as a tool.

A phonetic alphabet is a tool or medium not only because it extends our bodies but in the even more basic sense of something that goes between and brings together. What does a phonetic alphabet go between and bring together? Meaning and sound.

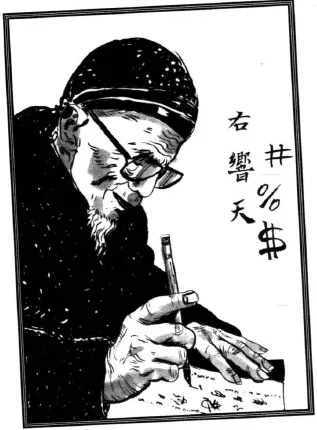

If we compare, say, Chinese characters, with a phonetic alphabet, we find no “go-between” in Chinese. The writing gives meanings, but it doesn’t show how to pronounce what is written.

If you are having trouble understanding this, think about symbols like + or $ or %. There is nothing in the shapes of these symbols to show how they are pronounced, but there is in the letters of plus, dollar, and percent. Imagine if every word in English was a symbol like + instead of plus, $ instead of dollar, or % instead of percent, and then you’ve got an idea of how Chinese works and how It is different from a phonetic alphabet.

What Does a Linguist Do from Nine to Five

Some linguists study one language and how its sounds vary in different places in a sound-group (p, for example, is not pronounced in exactly the same way at the beginning of a word in English—pot, and at the end—top). Some may examine the street slang of their own neighborhoods, but others may race to a far corner of the world to record conversations among the last few speakers of a dying language.

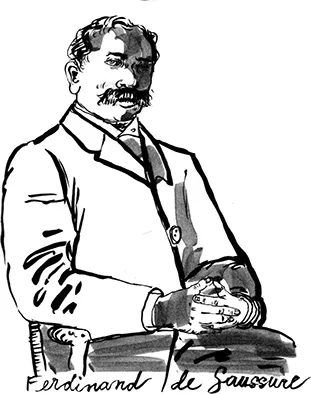

This is all modern linguistics, twentieth century linguistics, as it has been practiced since the time of Swiss scholar Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) and because of his influence. So far-reaching has this influence been that Sauseure is often called the father of modern linguistics. But what about earlier?

Is it not possible that people have been thinking about language for almost as long as they have been using it? In fact, we find the first flowering of linguistic thought twenty-two centuries before Saussure.

The French word linguistique had already been in use for at least 24 years when Saussure was born; its English cousin linguistic appeared first in 1837 in the writings of the British scholar William Whewell, who defined it as the science of language. Under the influence of American scholars such as Noah Webster and Dwight Whitney, linguistic was transformed into linguistics.

By comparison with linguistic(s), linguist has a much longer history, having been ...

Table of contents

- Coverpage

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Linguistics

- APPENDIX #1 Up for the Count

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Linguistics For Beginners by W. Terrence Gordon,Susan Willmarth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.