- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender & Sexuality For Beginners

About this book

What does sexual orientation mean if the very categories of gender are in question? How do we measure equality when our society’s definitions of “male” and “female” leave out much of the population? There is no consensus on what a “real” man or woman is, where one’s sex begins and ends, or what purpose the categories of masculine and feminine traits serve. While significant strides have been made in recent years on behalf of women’s, gay and lesbian rights, there is still a large division between the law and day-to-day reality for LGBTQIA and female-identified individuals in American society. The practices, media outlets and institutions that privilege heterosexuality and traditional gender roles as “natural” need a closer examination.

Gender & Sexuality For Beginners considers the uses and limitations of biology in defining gender. Questioning gender and sex as both categories and forms of compulsory identification, it critically examines the issues in the historical and contemporary construction, meaning and perpetuation of gender roles. Gender & Sexuality For Beginners interweaves neurobiology, psychology, feminist, queer and trans theory, as well as historical gay and lesbian activism to offer new perspectives on gender inequality, ultimately pointing to the clear inadequacy of gender categories and the ways in which the sex-gender system oppresses us all.

Gender & Sexuality For Beginners considers the uses and limitations of biology in defining gender. Questioning gender and sex as both categories and forms of compulsory identification, it critically examines the issues in the historical and contemporary construction, meaning and perpetuation of gender roles. Gender & Sexuality For Beginners interweaves neurobiology, psychology, feminist, queer and trans theory, as well as historical gay and lesbian activism to offer new perspectives on gender inequality, ultimately pointing to the clear inadequacy of gender categories and the ways in which the sex-gender system oppresses us all.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender & Sexuality For Beginners by Jaimee Garbacik,Jeffrey Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Human Sexuality in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE BIOLOGY OF SEX AND GENDER

When do we first become aware of gender? Is it when certain clothing or toys are given to us to match a culturally specific model of how a child should look and play? Is it when we see genitals other than our own and are forced to compare and contrast? Or maybe the first time we truly process the idea of gender occurs when checking off a box to identify ourselves, almost invariably as either “male” or “female.”

SEX VS. GENDER: A BASIC GLOSSARY

One's “sex” refers to the physical attributes that distinguish between typical male, female, and intersex people. “Gender,” on the other hand, refers to the behaviors, activities, roles, and actions that are socially attributed to boys, girls, men, women, and transgender people in a given society. Descriptions of genders and gender roles differ in each culture, and many people's gender (or genders) do not match the socially-designated attributes of the sex that they are assigned at birth. The term “gender identity” describes the gender that a person inhabits, experiences, and expresses in their daily life.

“Sexuality” refers to desire and attraction. One's “sexual orientation” indicates who one is generally attracted to, emotionally, romantically, and/or sexually. People can be attracted to members of their own sex or a different sex, to more than one sex or gender, or not experience attraction at all. Some people also have emotional and romantic feelings for people they are not sexually attracted to (or sexual attraction to someone they do not have romantic or emotional feelings for); this also falls under one's sexual orientation. A “sexual identity” describes how someone feels about or relates to their sex, gender(s), and sexual orientation.

Neurobiologists often suggest that the formation of gender identity starts much earlier than any of these events. Some say that gender is simply embedded in our genes. Others believe that the introduction of particular hormones in the womb shape how we will emerge. It is commonly held that the number of X vs. Y chromosomes an individual has in their cells provides the basic determination of an individual's sex. And yet, few contest that chromosomes fall quite shy of explaining the roles and patterns of behavior that are associated in our society with being a man or a woman. What's more, there are plenty of individuals who don't fall neatly into either of these categories, either biologically speaking or with regards to their personality and sense of identity. And, of course, being a man or a woman (as well as combinations thereof and other identity classifications entirely) has meant different things to different cultures throughout the course of history. These categories continue to evolve as economics, politics, popular culture, art, science, and other factors shift society's perception of itself, and alter the roles which comprise our collective and individual sense of identity.

SEX ASSIGNMENT AND GENDER DOCUMENTATION

It is telling that very few surveys, tests, or paperwork requiring someone to check a box noting their sex or gender provide alternative options to “male” or “female.” In the majority of binding legal, medical, and governmental documentation it is assumed that gender is fixed, assigned at birth, and has no room to evolve, change, or fall outside those two boxes. When a doctor signs a legally binding birth certificate, they personally and permanently assign a child's sex, which can only be changed through complex legal proceedings that vary by state.

When examining gender as a category, one of the first distinctions we explore is dividing people on the basis of their genitals, hormones, or chromosomes. Although, is this not as arbitrary as dividing the world up on the basis of left-and right-handedness or by eye color? Such logic may be valid in theory, but dividing people on the basis of handedness or eye color would ignore the historical and cultural meaning, weight, and power assigned to a man or a woman. On the other hand, separating people according to genitals, hormones, and chromosomes ignores the experience of transgender, intersex, androgynous, and genderqueer people (to name a few categories).

For this discussion, the categories of male and female will be overrepresented due to the amount of pertinent study that has strictly attended to those two identities. It should nevertheless be noted that on almost every continent throughout history, a variety of cultures have acknowledged more than two genders. Western society's currently rigid description of people as deterministically “one or the other” leaves little room for variation in one's experience of a mixed or changing gender identity, gender expression, or variance within what the words “men” and “women” signify. Even progressive terms like “transgender” are sometimes employed in ways that imply that there are “normally” two sexes (male and female) and two genders (man and woman). This leaves out equally legitimate identities such as “nádleehí,” a designation in Navajo culture for an individual who considers themself both a boy and a girl. The Navajo are far from the only culture with a malleable concept of gender identity, but Western traditions have marginalized all but a binary notion of gender, and by extension, the sexuality of those genders.

GENETICS 101

DNA contains the genetic instructions that manage the development of all living organisms. These molecules store information in a codelike fashion. The segments carrying this data are referred to as genes. Genes pass on traits between generations of organisms and determine what characteristics each individual organism will inherit. For example, there is a gene for eye color.

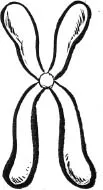

A chromosome is a structure of DNA and protein that is found in cells. Chromosomes organize DNA into a discrete package that regulates its genes’ meaning and expression. In humans, there are two kinds of chromosomes: autosomes and sex chromosomes. The traits which are connected to someone's sex are transmitted through their sex chromosomes. All other hereditary information resides in autosomes. All human cells contain 23 pairs of nuclear chromosomes—1 pair of sex chromosomes and 22 pairs of autosomes.

Most people have one pair of sex chromosomes per cell; usually, females have two X chromosomes and males have one X and one Y. Both sexes retain one of their mother's X chromosomes, and females inherit a second X chromosome from their father. Males inherit their father's Y chromosome instead.

Although X chromosomes contain several thousand genes, almost none (if any) relate specifically to the determination of sex. As females develop in the womb, one of their X chromosomes is almost always deactivated in all cells (except for in egg cells). This process guarantees that both males and females have one working copy of the X chromosome in each cell. The Y chromosome contains the SRY gene which prompts testes to develop, distinguishing male organisms from females. Y chromosomes also house the genes that produce sperm.

MALE = OF OR DENOTING THE SEX THAT PRODUCES SMALL, TYPICALLY MOTILE GAMETES.

FEMALE = OF OR DENOTING THE SEX THAT CAN BEAR OFFSPRING OR PRODUCE EGGS.

In the Oxford English Dictionary, a male is “of or denoting the sex that produces small, typically motile gametes, especially spermatozoa, with which a female may be fertilized or inseminated to produce offspring.” This definition is strictly biological, and refers only to a male's ability to impregnate a female. To some biologists, this is the only characteristic which differentiates the male sex in an inarguable fashion. A female, by contrast, is “of or denoting the sex that can bear offspring or produce eggs, distinguished biologically by the production of gametes (ova) that can be fertilized by male gametes.” By this account, an animal, plant, or human is a female if “she” can produce eggs and therefore bear children or offspring.

Doctors assign humans’ sex at birth on the basis of genitalia, not the ability to reproduce. Likewise, doctors seldom check individuals to verify whether or not they have XX or XY chromosomes, but generally assume the presence of a penis or a vagina is indicative of these chromosome pairings.

VIRILITY AND FERTILITY

Legally-speaking, a woman who cannot conceive or a man who cannot inseminate a female is not considered any less representative of their sex. Still, there are definitely social connotations surrounding women's infertility and men's virility. For example, men who are impotent (or assumed to be on the basis of exhibiting fewer masculine traits) are sometimes mocked by their peers. Likewise, women who are unable to bear children or choose not to sometimes experience stigmatization.

This is not always the case, as with intersex people who may have both male and female genitalia, atypical genital and/or reproductive anatomy, or ambiguous sex characteristics. Being intersex is relatively common, occurring in 1.7 percent of the population. Intersex people sometimes have gonosomes (sex chromosomes) that are different from the most typical XX-female or XY-male presentations. According to the Intersex Society of North America, intersex genitals “may signal an underlying metabolic concern, but they themselves are not diseased; they just look different. Metabolic concerns should be treated medically, but [intersex] genitals are not in need of medical treatment.”

CHROMOSOME

Despite the fact that intersex genitals do not require treatment, there is a history of medical practitioners stepping in and performing surgeries that carry significant risk to intersex infants which has had a pathologizing effect on intersex people and their families. As biologist, historian, and feminist Anne Fausto-Sterling explains, “If a child is born with two X chromosomes, oviducts, ovaries, and a uterus on the inside, but a penis and scrotum on the outside…is the child a boy or a girl? Most doctors declare the child a girl, despite the penis, because of her potential to give birth, and intervene using surgery and hormones to carry out the decisions. [But] choosing which criteria to use in determining sex, and choosing to make the determination at all, are social decisions for which scientists can offer no absolute guidelines.” Because these “normalizing” surgeries are generally irreversible, if they are performed at birth or in infancy without the individual's consent, they also run a serious risk of assigning a sex that may not fit the child's identification when they grow up.

INTERSEX SURGERIES TODAY

While “normalizing” surgeries are now less commonly advised at birth by medical professionals, some parents of intersex infants still request them. Individuals with intersex characteristics may more safely opt for a surgery later in life to more clearly distinguish their sex. Such a surgery is not automatically necessary or desirable for life or health. It is usually performed mainly to ease social and sexual interactions, or to help an intersex person achieve a lack of ambiguity about their gender. These surgeries can sometimes result in difficulty with sexual functioning later in life, in problems with fertility, continence, or sensation; they can also be life-threatening.

Aside from chromosomes and genitals, there are other physical characteristics that are commonly used to distinguish between males and females, but they are far from foolproof and do not indicate one's gender identity. Secondary sex characteristics are physical features that occur more frequently in either male or female members of a species, which do not relate to reproduction or sex organs. In humans, most secondary sex characteristics are fairly similar in male and female children until puberty, when hormone levels increase and result in both similar and different changes to the body.

In males, once puberty hits, facial and body hair growth occurs (abdominal, chest, underarm, and pubic), as well as a possible loss of scalp hair, enlargement of the larynx, and a deepened voice. Their shoulders and chest will broaden as they gain more muscle mass, a heavier skull and bone structure, and larger stature in general (males, on average, are taller than females). A male's face will also become more square, and their waist will narrow (though it typically remains wider than in females).

Females, by contrast, experience breast growth and nipple erection during puberty, as well as widening of their hips, and a rounder face. Females generally develop smaller hands and feet than males. They grow some body hair during puberty as well, but it is mostly limited to the underarm and pubic areas. Their upper arms are generally a bit longer than men's, proportionately, and their weight distribution will change, distributing more fat into the thighs, hips, and buttocks. There are also a variety of other changes occurring in puberty to male and female sex organs, but these are not considered secondary sex characteristics.

Sometimes individual or several secondary male sex characteristics may be present in a female-identified person, or the reverse, complicating a “common sense” definition of what makes a “man” or “woman.” For example, some males retain erect nipples or develop tissue in their pectoral muscles, resulting in a chest similar in appearance to female breasts. Many females grow some facial hair on their chin or upper lip, or have square jaw lines. People of both sexes often have larger or smaller feet, hands, thighs, or buttocks than is typical of their assigned sex. Plenty of males are short or have high voices; lots of females are tall or have low voices. Suffice to say, while secondary sex characteristics describe the “average” male and female traits, very few real people fit neatly into that “average” box.

ONLY TWO SEXES?

Recently, the “general reducibility” of the biological sexes to male and female has been called into serious question by various biological researchers and feminists who posit that beliefs about gender may “affect what kinds of knowledge scientists produce about sex.” For example, grouping and sampling methods may reflect and reinforce ideas of “hardwired” sex-specific intelligence and behaviors in studies that seek to examine sex differences in the brain. Without these preconceptions, it's possible that we might find several distinct sexes, or at least a blurrier boundary between males and females.

It is possible to use gonads (gametes that make ova or sperm; i.e., ovaries and testicles) and chromosomes as the basis for differentiating females from males, but this leaves a lot of gray area regarding many people's more ambiguous primary or secondary sex characteristics. While the vast majority of babies’ genitalia may be clearly regarded as biologically male or female, their chromosomes may not reflect that assigned sex. They may develop secondary sex characteristics later that complicate that definition. Furthermore, once one's sex is assigned, the way in which an infant is treated by its parents, caretakers, and everyone they meet will be profoundly shaped by assumptions about the child's sex. Being raised as a boy, girl, a combination of the two, or identifying as neither is in many respects an entirely separate concern from one's sex.

Gender differs from one's assigned sex in that it can be self-defined. Doctors may look at a baby's genitals and say that it is a male, but the baby itself, in tandem with their parents’ rearing and social experiences, will ultimately define what gender it is identified as. The distinction between a biological sex and a gender “role” was first introduced by the work of sexologist John Money in 1955. Before that, “gender” was strictly a grammatical term that referred to words with masculine or feminine connotations within a given culture. For example, in most languages derived from Latin (“romance languages,” which...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Who Said That?

- Introduction

- 1: The Biology of Sex and Gender

- 2: Historical Construction of Gender Roles

- 3: Feminism

- 4: Modern Construction of Gender Roles

- 5: Sexual Orientation

- 6: Gay and Lesbian Activism

- 7: Queer Theory

- 8: Transgender Contexts and Concerns

- Looking Forward

- Resources

- Timeline

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements