- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The History of Classical Music For Beginners

About this book

Music history is nearly as old as human civilization itself, and while it has permeated the arts and popular culture for centuries, it still has this mystifying aura surrounding it. But fear not—it’s not as complicated as it seems, and anyone can learn the origins and history of Western art music. In addition to learning how better to understand (and enjoy!) classical music, The History of Classical Music For Beginners will help you will learn of some of the more interesting and sometimes comical stories behind the music and composers.

Did you know that Jean-Baptiste Lully actually died from conducting one of his own compositions? You may have heard of Gregorian chant, but did you know there are many forms of chant, including Ambrosian and Byzantine chant? And did you also know that only a small portion of “classical music” is even technically Classical?

These interesting, insightful facts and more are yours to discover in The History of Classical Music For Beginners.

Did you know that Jean-Baptiste Lully actually died from conducting one of his own compositions? You may have heard of Gregorian chant, but did you know there are many forms of chant, including Ambrosian and Byzantine chant? And did you also know that only a small portion of “classical music” is even technically Classical?

These interesting, insightful facts and more are yours to discover in The History of Classical Music For Beginners.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The History of Classical Music For Beginners by R. Ryan Endris,Joe Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 11

THE BEGINNINGS OF A NEW STYLE

Between the years of 1600 and 1750, a period later referred to as the Baroque period, history sees significant developments in music, art, and architecture. Originally, the term baroque, originally from the Portuguese barroco for “misshapen pearl,” meant abnormal, exaggerated, bizarre, or even being bad in taste. It was a negative term applied by critics in the mid-1700s who preferred the earlier styles of the Renaissance. In the mid-nineteenth century, the term took on a more positive connotation, as critics began to appreciate the dramatic, ornate, and expressive characteristics of the arts during the Baroque. As was the case with music of the Renaissance, the 150-year span of the Baroque encompassed a wide range of styles and musical developments.

Remember the doctrine of affections discussed in Chapter 1? In the Baroque, composers gave the strongest push towards the emotional qualities of music since antiquity. Composers sought, through music, to arouse the affections of listeners. These affections, or emotions, ranged from sadness, to joy, to anger, to excitement. These affections were caused by spirits, or “humors,” in the body. By bringing these emotional states into harmony, persons would enjoy both physical and psychological health. Use of contrasting affects in music, then, would aid in realizing this balance of the affections. Music in the Baroque did not seek to express the composer's personal feelings, but rather sought to portray affections generically. In vocal music, composers aimed to capture the emotions, character, and drama of the text.

One of the defining characteristics of the early Baroque was the development of a second practice (seconda prattica). The prima prattica, or “first practice,” referenced the sixteenth-century style of polyphony that we have just learned about in the past few chapters. The first practice focused on the rules that musical composition must follow, with a model of music dominating the text. The second practice, in contrast, placed even more emphasis on conveying the meaning and emotion of the text. This, in turn, led to the breaking of established rules of composition, introducing more dissonance into music to more convincingly convey the feelings and meaning of the text. It is important to note that the seconda prattica did not replace the prima prattica; rather, the two styles existed side by side, each being used as deemed appropriate by the composer.

In general, the Baroque period exhibits a number of stylistic traits that distinguish it from earlier periods. One of the major characteristics of Baroque music is a distinguished polarity between a treble voice (with treble meaning “pertaining to the highest voice) and an accompanying bass line (the lowest voice) that dictated the realization of harmonies. The style of the Renaissance evolved to place equal emphasis on all voices of a composition, voices that were entirely independent of each other. Seventeenth-century music, on the other hand, yielded a great amount of music written in homophonic textures, with the bass and treble voices being most prominent and inner voices simply “filling in” the harmony.

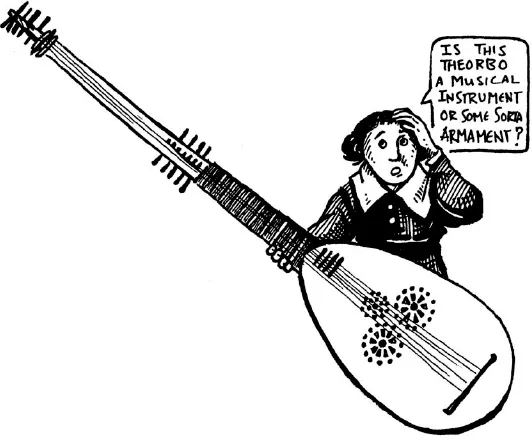

Another defining characteristic of the Baroque period was the development of a convention known as basso continuo. Italian for “continuous bass,” composers wrote out melodies and a bass line, with the performers of the bass line left to fill in the appropriate harmonies according to figures indicated by the composer. While basso continuo became the standard practice in the Baroque, one should know that not every single piece called for basso continuo. As the role of basso continuo was accompaniment, it was obviously unnecessary for solo works for lute and keyboard instruments What is important to remember is that basso continuo refers not to a single performer, but rather a group of instrumentalists known as the continuo group. The number of players in the continuo group was rarely prescribed by the composer, was flexible, and could vary from composition to composition; however, the continuo group always consisted of specific types of instruments. A typical continuo group always consisted of at least one keyboard instrument (usually harpsichord, but sometimes with organ in cases of sacred music) and at least one bass stringed instrument, such as viola da gamba or cello. Additionally, the continuo group might include strummed instruments such as the lute or theorbo, or it might include a low-sounding wind instrument like the bassoon to reinforce the base line.

The symbols indicated below the bass line were known as figured bass, a notational system that informed the performer of the harmonies that should be realized in a composition. The realization of these figures in performance led to a wide variety of interpretations, interpretations which varied based on the style of the piece and the particular tastes and skills of the player. Realization of figured bass was quite improvisatory in nature, as the performer had great latitude in their interpretation of the music. The basso continuo player might begin by playing only the bass line, then adding in a few chords based on the figured bass. Then the player might continue by doubling the treble voice, adding ornaments and embellishments as the player felt necessary.

Several other developments and practices marked the Baroque period as distinct from previous compositional styles. Composers in the seventeenth century frequently wrote music for both voices and instruments, each playing different parts. This is a significant departure from Renaissance music, in which instruments typically doubled the vocal parts (or played vocal music without any singers). This resulting practice became known as the concertato medium, which comes from the Italian concertare, “to reach agreement.” The overriding concept is that a variety of contrasting voices and instruments are brought together harmoniously in a single musical work known as a concerto. Later in the seventeenth century and beyond, we will come to understand the concerto as a composition for soloist and orchestra, but in the early seventeenth century the meaning of concerto was much broader.

The other two major hallmarks of Baroque music were the use of ornamentation and the shift from modal music to tonal music. Ornamentation, used sparingly (if at all) in the Renaissance became the norm in the Baroque. Aside from demonstrating a performer's individual style, ornaments or embellishments were frequently employed to aid in moving the affections. Ornaments occurred on a local level (such as trills added to a particular note), but they also occurred on a global level. For example, the cadenza—an extended elaborately-decorated passage demonstrating the virtuosity of the performer—was a common way of bringing a piece of music to a close. The church modes, which had long dominated the music of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, no longer characterized music. Instead, composers were writing in a harmonic language we now call tonal music, the system of writing in major and minor keys that are familiar with today. While some of the practices of the Baroque eventually felt out of fashion (such as basso continuo), others remain with us today, such as the development of tonality to replace modal music.

Chapter 12

CHAMBER AND CHURCH MUSIC IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

In the seventeenth century, music continued to serve very specific roles: secular music to be performed for social events, entertainment, the chamber, and theatre and sacred music to be performed in churches. Italy's role as a leader in musical innovation in Europe continued to flourish in the seventeenth century, both in chamber music and church music. While opera was the main focus of musical culture in Venice, the rest of Italy enjoyed a surge in secular music that was designed for small audiences. Music involved ensembles of voices and instruments for amateur musicians and the listening enjoyment of their peers. While strophic songs continued to be popular with the masses, the elite enjoyed vocal chamber music in a variety of forms and styles, many of which combined characteristics of madrigal, dance music, and dramatic music.

A survey of music history limits the ability to do justice to all forms of secular vocal music in the seventeenth century, so this chapter will focus on the three principal developments in song: concertato works, basso ostinato, and the cantata. In the previous chapter we learned that the concertato medium employed both voices and instruments playing individual parts. Italian composers churned out thousands of pieces for voice and accompanying basso continuo, sometimes with additional instruments. While many of the works were composed for one to three voices, some featured as many as six voices (and sometimes more!). Many of these songs were known much more widely than the operas of the time, and thus they became the music of the people.

The concerted madrigal, in particular, marks a major departure from the unaccompanied, polyphonic madrigal of the Renaissance. While styles ranged from imitative polyphony mirroring the sixteenth century to the stile concitato (the “excited style”) of the seventeenth century, nearly all of these concerted madrigals employed a basso continuo. These madrigals were often set for one to three voices, but they occasionally called for additional instruments, resulting in instrumental introductions and ritornellos.

Of these concerted works, a number of them employed a technique called basso ostinato (also known as a ground bass). The basso ostinato was a compositional method where a short pattern in the bass would be repeated continuously over an ever-changing melody and harmony above it. The Italians don't get full credit for this one—the technique had already been in use for many years in the popular songs of Spain as well. Specific types of ground bass include the lament bass (a descending pattern of four notes known as a descending tetrachord) and the chacona (a lively dance-song form brought from Latin America to Spain and eventually to Italy). The descending tetrachord was called a lament bass because the pattern of falling pitches conveyed a sense of hopeless sorrow. The chacona (ciaccona in Italian), in contrast, was lively and upbeat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Music of the Ancient and Medieval Worlds

- II. A Rebirth: Music of the Renaissance

- III. The Baroque Period: The Music of Bach and Vivaldi

- IV. Finally! Classical “Classical Music”

- V. It's Not All Lovey-Dovey: the Romantic Period

- VI. Bucking the Trend: Music in the Twentieth Century

- Glossary

- About the Author

- About the Artist