- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

French Revolutions For Beginners

About this book

Allons enfant de la Patrie, le jour de gloire est arrivé!

“Arise children of the Fatherland, the day of glory has arrived!” These opening lines to La Marseillaise, France’s famously stirring and evocative national anthem, capture perfectly the passion, fear, and frenetic energy of Republicanism’s sanguinary birth on French soil. Through the violence of the Revolutions (yes there were many) the reign of the Bourbon monarchy came to an end and modern France was born.

French Revolutions For Beginners examines the several bloody revolutions and counter-revolutions throughout the course of the 19th century and the constant upheavals and disruptions in France’s ever changing political landscape from 1789-1900. While most people have some familiarity with names like Louis XVI and Napoleon, the details of what exactly happened during the French Revolution – apart from pithy royal pronouncements about cake eating and the ever-falling blade of the guillotine – are often difficult to understand, and for good reason: there were a whopping 15 changes of government in less than a century! The legacy of the French Revolutions remains with us today; we see it all over the world when an oppressed people rise up against an authoritarian regime demanding their rights as citizens be recognized.

French Revolutions For Beginners presents the major political figures, events and hot-button political issues of this extremely violent, chaotic, confusing – but always exciting – period in a way that is accessible, interesting, and fun to both history-buffs and the neophyte alike.

“Arise children of the Fatherland, the day of glory has arrived!” These opening lines to La Marseillaise, France’s famously stirring and evocative national anthem, capture perfectly the passion, fear, and frenetic energy of Republicanism’s sanguinary birth on French soil. Through the violence of the Revolutions (yes there were many) the reign of the Bourbon monarchy came to an end and modern France was born.

French Revolutions For Beginners examines the several bloody revolutions and counter-revolutions throughout the course of the 19th century and the constant upheavals and disruptions in France’s ever changing political landscape from 1789-1900. While most people have some familiarity with names like Louis XVI and Napoleon, the details of what exactly happened during the French Revolution – apart from pithy royal pronouncements about cake eating and the ever-falling blade of the guillotine – are often difficult to understand, and for good reason: there were a whopping 15 changes of government in less than a century! The legacy of the French Revolutions remains with us today; we see it all over the world when an oppressed people rise up against an authoritarian regime demanding their rights as citizens be recognized.

French Revolutions For Beginners presents the major political figures, events and hot-button political issues of this extremely violent, chaotic, confusing – but always exciting – period in a way that is accessible, interesting, and fun to both history-buffs and the neophyte alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access French Revolutions For Beginners by Michael J. LaMonica,Tom Motley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

X

A REPUBLIC OF VIRTUE – A REPUBLIC OF TERROR

To establish a definitive break with the past, in October of 1793, the Convention voted to adopt a new Republican calendar. The old Gregorian calendar with its irrational assortment of days and months named after old gods and kings wasn't befitting this new modern era. The new calendar was decimally sublime: each month consisting of three, ten-day weeks, and each day consisting of ten, 100-minute hours. While it never quite caught on, the Committee of Public Education (far less feared than the Committee of Public Safety, at least to non-students) extended this principle to measurements of length, creating the forerunner of the modern metric system. Rather than date the year from the birth of Christ, henceforth the years would be dated from September 22, 1793, the day the Republic was proclaimed and history began anew. In keeping with the Enlightenment era reverence for nature, the months were given descriptive names like Brumaire (“fog” for October), Ventôse (“windy” for February), Prairial (“pasture” for May), and Thermidor (“heat” for July).

Part of the motivation behind the new calendar was to deinstitutionalize the role of the Catholic Church in French life. Things had been going downhill for the Church ever since the split over the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790. As the Revolution grew more radicalized, people began to see the Church, with its monarchial pope and close alliance to archrival Austria, as a counter-revolutionary agent provocateur of the old regime. A new religion, dedicated to the principles of reason, equality, justice, liberty, and natural law was needed to replace superstitious and royalist Catholicism. A group of far-left ultra-revolutionaries known as the enragés (“the enraged ones,” we'll see them again later) took up the cause and pursued a policy of dechristianization. Mobs roamed the countryside looting churches (the term vandalism arose during this period), smashing relics, beheading saints, and forcing priests to adjure their faith and marry on pain of death. They created a new religion, the Cult of Reason, to promote revolutionary ideology. Atheistic and civic-minded, this new religion promoted the worship of pure reason and celebrated festivals commemorating virtue, philosophy, and natural cycles to replace the old high holy days. They even transformed the famous Cathedral of Notre Dame into a Temple of Reason, and celebrated the first Festival of Reason on November 10, 1793. Soon after, the Convention officially banned all forms of Christian worship throughout the country. No church bell would ring again in France for another two years.

On August 28, 1793, a British fleet captured the port city of Toulon and destroyed France's entire Mediterranean fleet. Making matters worse, they were able to sail in unopposed after royalists took control of the city and let the British in. It was France's greatest military disaster to date and sent the Convention into a panic. Just one month prior, on July 13, a Girondin sympathizer by the name of Charlotte Corday entered Marat's room and stabbed him to death while he was in the bathtub.

This act, combined with the ongoing revolts throughout the country, convinced the Committee of Public Safety that radical measures were needed to safeguard the Revolution from its enemies, both foreign and domestic. On September 17, they passed a decree known as the Law of Suspects. It established a secret police force of ‘surveillance committees’ and deputized them to arrest anyone who “showed themselves to be supporters of tyranny, of federalism, or to be enemies of liberty.” This mushy standard meant that anyone viewed as being too ‘aristocratic,’ or even just insufficiently supportive of the Convention ran the risk of being hauled before the Revolutionary Tribunal. Enforcing this decree were the sans-culottes, increasingly the personal paramilitary force of Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety. Until they could safely secure the Republic from the clutches of her enemies, Terror, the Committee famously declared, would be the order of the day. When the Terror finally ended nine months later, over 17,000 people had been left a head shorter under the merciless falling blade of the ‘National Razor.’

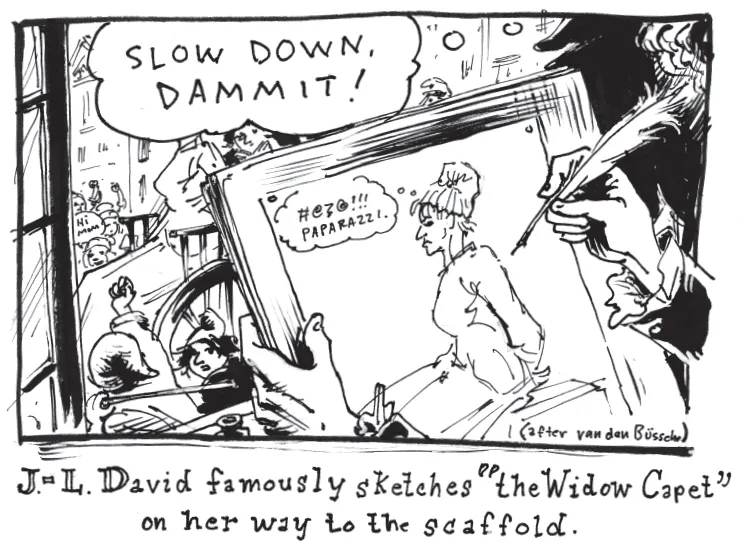

This period, appropriately called the Reign of Terror, is perhaps the most well-known of the entire Revolution. Ironically, the quick, ‘humane’ (even clinical) death offered by the guillotine enabled the rapid execution of thousands of people in a way the old, more personal forms of execution under the old regime never could. The widowed former Queen, Marie Antoinette, became the Terror's first famous victim on October 16. Closely following her two weeks later was the Girondin leadership, arrested back in May. In November, Philippe Égalité, the former Duke of Orléans, followed his cousin Louis XVI to the scaffold. Bailly, the first revolutionary mayor of Paris under the Commune and former President of the National Assembly, long hated by the sans-culottes for his role in the Champ de Mars Massacre, went next. Many more would follow in 1794.

The foremost proponent of the Terror was the representative from the Aisne, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, popularly called the ‘Angel of Death.’ Robespierre admired the young man's revolutionary zeal, and Saint-Just looked up to Robespierre as an idol. While the two developed a mentor-protégé relationship, Saint-Just was always the more extreme of the two and pushed Robespierre in that direction. Unlike Robespierre's vision of an Arcadian Republic of Virtue, Saint-Just modeled his ideal republic on ancient Sparta. In his fantasy world, the State would remove young boys from their mothers at age six and raise them to be warriors, statesmen, scholars, or laborers based on their merits. The State would hold all property in common and use it for the betterment of the Republic as a whole. He pursued these ideas in his notorious (and never fully implemented) Ventôse Decrees, which proposed the confiscation of all property held by émigrés and convicted traitors, with the State redistributing them to true revolutionaries.

While Robespierre abhorred violence of any form, he believed that harsh measures were necessary to save the Republic. Saint-Just took a much more sanguine attitude towards killing and viewed the Terror as a kind of crucible – one that would remove the weaknesses and impurities from society, leaving behind a pure, hardened revolutionary alloy. Saint-Just saw no need to cloak violence in euphemism or Terror in high-minded justifications, but spoke plainly about his intent. Not only traitors deserved death according to Saint-Just, but also those who were merely indifferent, passive, or apathetic. Never one for understatement, he delivered famously grisly lines on the floor of the Convention such as, “a nation generates itself only upon heaps of corpses,” and that “the vessel of the Revolution can only arrive safely in port on a sea reddened with torrents of blood.” Saint-Just quickly developed a heated rivalry with old guard revolutionaries Danton and Desmoulins, viewing them as soft appeasers, while they saw him as a pompous, self-righteous upstart.

The Committee used the guillotine not only to weed out counter-revolutionaries (both real and imagined) but also as a tool of political oppression. With the Girondins dead or in hiding, the Jacobin faction was now supreme in both the Convention and Committee of Public Safety. As often happens in these situations, the once unified Jacobins split into an extremist faction, the enragés led by Hébert, and a moderate faction, the indulgents led by Danton.

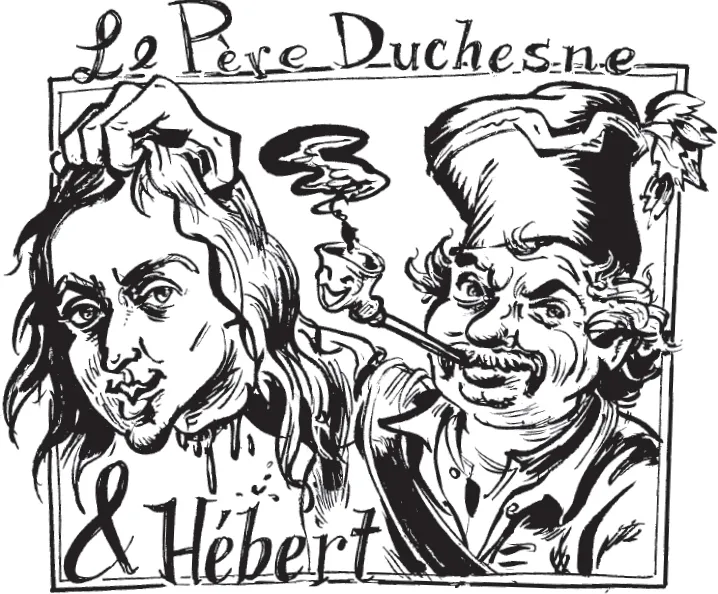

Jacques Hébert was a political journalist who became wealthy and famous through his radical newspaper, Le Père Duchesne. Before the Revolution, most political papers were self-consciously highbrow and written for a bourgeois audience. In 1790, Hébert had the idea of making a newspaper that the everyday working man could relate to. He created a character named Père Duchesne, a vulgar, pipe-smoking, furnace maker, who could act as a mouthpiece for Hébert. The paper, with its coarse dialogue, dirty jokes, and violent rhetoric, quickly became a favorite of the sans-culotte crowd. When Hébert won a lucrative government contract to distribute his papers to the armies in 1792, he became an extremely rich and influential man. After Marat's assassination in July of 1793, Hébert positioned himself to carry on the literary torch of extreme, radical revolution.

Politically to the left of the Jacobins, Hébert's enragés advocated for open class warfare and pressed for a sharply progressive income tax along with strong state controls over the economy. In part to appease the enragés, in September of 1793, the Convention passed a General Maximum (not to be confused with General Maximus) putting sharp price controls on food and other essentials. While intended to stop price gouging and allow people to buy necessities at rates they could afford, the hyperinflation of the assignat and low prices set in the Maximum meant that merchants actually would be taking a loss by selling these items. Predictably, merchants refused to stock the products or sold them on the black market, resulting in even more scarcity. The lack of food led to more demands by the enragés for the government to crack down on ‘speculators’ while hundreds of merchants were denounced as hoarders and forced to appear before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

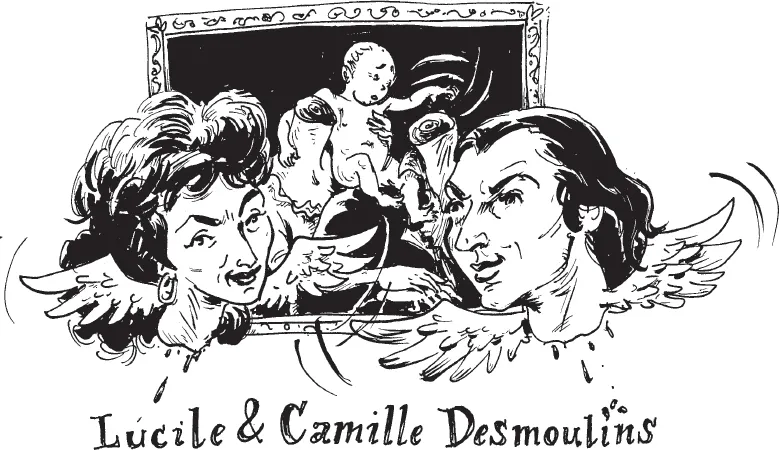

Opposite the enragés were the indulgents, ironically led by the radicals of yesteryear, Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins. It's generally a good indicator that a revolution has passed you by when your once far-left, progressive views become regarded as stodgy and conservative. While both men were principal agitators of the fall of the Bastille, the Champ de Mars massacre, and the assault on the Tuilieries, the purge of the Girondins soured them on the course the Revolution was taking. The Terror was becoming self-perpetuating as people denounced their neighbors to avoid being denounced themselves. The Committee of Public Safety had assumed total control over all aspects of government with Robespierre acting as virtual dictator. They realized that the Republic could not survive with constant war abroad and terrorism at home; France must make peace with her neighbors and dissolve the Committee to usher in normal, constitutional government. As a rebuke to the new blood who had hijacked their revolution, Desmoulins published a journal titled Le Vieux Cordelier (“The Old Cordelier,” or “I was a Cordelier before it was cool”), wherein he rejected the enragés and called for an end to the Terror.

In December of 1793, French forces succeeded in booting the British out of Toulon, thanks to the genius of a young Corsican artillery officer who only spoke French with a thick Italian accent and had the foreign-sounding name Napoleone Buonaparte. In recognition of his victory, the Convention promoted him to the rank of general and gave him command of an army. He would soon after assume the more French-sounding name history knows him by: Napoleon Bonaparte.

With the foreign situation under control once again, Robespierre could now consolidate his power going into 1794. The violent and disruptive ultra-revolutionary enragés were a constant thorn in his backside. As a serious and contemplative man, Robespierre despised Hébert and his tactics for making a mockery of his Republic of Virtue. While not religious himself, Robespierre believed in a Deist conception of a Supreme Being and understood the pragmatic value religion held in the lives of most people. Their attacks against religion were turning the countryside against the Convention and giving France's enemies easy propaganda to use against them. In yet another of the Revolution's countless ironies, the anti-death penalty Robespierre joined with his estranged indulgent friends, Danton and Desmoulins, to take down Hébert's faction Godfather-style.

Robespierre first used his influence to remove officials loyal to Hébert from office while Desmoulins attacked him in Le Vieux Cordelier, accusing him of corruption and accepting bribes from the British. Hébert saw the noose tightening around his neck; he would need to strike down Robespierre before it was too late. If he could rally the sans-culottes behind him, they would march on the Convention and demand the arrest of Robespierre, Danton, and Desmoulins just like they did to the Girondins the year prior. On March 6, 1794, Hébert called for an insurrection against the disloyal indulgent faction and the dictator Robespierre, yet few sans-culotte partisans joined his causes. Even the typically radical Paris Commune was strangely silent. Robespierre had played his hand perfectly by cowing potential opposition while simultaneously luring Hébert into declaring an open rebellion. Now the trap snapped shut. Saint-Just, Robespierre's right hand man in the Committee, denounced Hébert and his allies as traitors to the Nation. They were quickly arrested, tried before the Tribunal, and sent to the guillotine on March 24. Hébert, the man whose writings casually condemned so many others to death, reportedly fainted several times on his way up the scaffold.

With Père Duchesne's pipe permanently snuffed and the power of the enragés broken, the tireless crosshairs of the Committee fell next on its biggest critics, the indulgent faction of Danton and Desmoulins. The blood-thirsty Saint-Just, foremost proponent of the Terror, particularly hated the indulgents and sought to destroy them. Undeterred, Desmoulins ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION: YOU SAY YOU WANT A REVOLUTION?

- II: THE ANCIEN RÉGIME: WHEN IT WAS GOOD TO BE THE KING

- III: SLOUCHING TOWARD REVOLUTION

- IV: THE DAM BREAKS: THE ESTATES-GENERAL OF 1789

- V: HAPPY BASTILLE DAY!

- VI: WORKING TOWARDS A CONSTITUTION

- VII: A ROYAL PAIN: THE FLIGHT TO VARENNES AND THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY

- VIII: THE CENTER CANNOT HOLD: THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY TO THE NATIONAL CONVENTION

- IX: VIVE LA RÉPUBLIQUE!

- X: A REPUBLIC OF VIRTUE – A REPUBLIC OF TERROR

- XI: THE DIRECTORY: A GOVERNMENT AS EXCITING AS IT SOUNDS

- XII: NAPOLEON'S RISE: THE FRENCH CONSULATE

- XIII: NAPOLEON'S TRIUMPH: THE FIRST FRENCH EMPIRE

- XIV: NAPOLEON'S DOWNFALL: THE END OF THE EMPIRE AND THE HUNDRED DAYS

- XV: TURNING BACK THE CLOCK ON THE REVOLUTION: THE CONGRESS OF VIENNA AND BOURBON RESTORATION

- XVI: THE BOYS OF SUMMER: LOUIS-PHILIPPE AND THE JULY MONARCHY

- XVII: FRENCH REVOLUTION OF 1848 AND THE SECOND REPUBLIC: WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU RUN OUT OF KINGS TO OVERTHROW

- XVIII: NAPOLEON III: THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

- XIX: FIGHTING GERMANS AND COMMUNISTS: THE TWENTIETH CENTURY BECKONS

- XX: THE END OF A WILD RIDE: THE LEGACY OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONS

- WORKS CONSULTED

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- ABOUT THE ARTIST