eBook - ePub

The Role of Microfinance in Women's Empowerment

A Comparative Study of Rural & Urban Groups in India

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Role of Microfinance in Women's Empowerment

A Comparative Study of Rural & Urban Groups in India

About this book

While the important topic of women's empowerment through microfinance has been the subject of academic and practitioner interest, Ramchandani examines these issues from brand-new perspectives. This new work focuses on the Self-Help Group (SHG) model, an under-studied aspect of microfinance practice, and looks at both rural communicates and urban slums. Ramchandani presents recent empirical work from India including first-hand field-level case studies, where microfinance plays a key development role in reducing poverty, addressing women's empowerment, and fostering rural economic growth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Role of Microfinance in Women's Empowerment by Raji Ajwani-Ramchandani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & International Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER

1

Introduction

1. Introduction

Understanding empowerment of women is a complex exercise. Trying to decipher whether microfinance has facilitated it is even harder. I’ve been trying to understand the connection between the two for the last six years, and to be honest just feel that whatever little that I have seen, experienced and understood is merely the tip of the iceberg. So much of what a woman perceives often described by the term ‘power within’ is dependent upon factors such as her socio-economic environment, education level, physical well-being, emotional state, support structures be it family, friends, community members or groups of like-minded individuals that she may be associated with in the course of her daily life.1

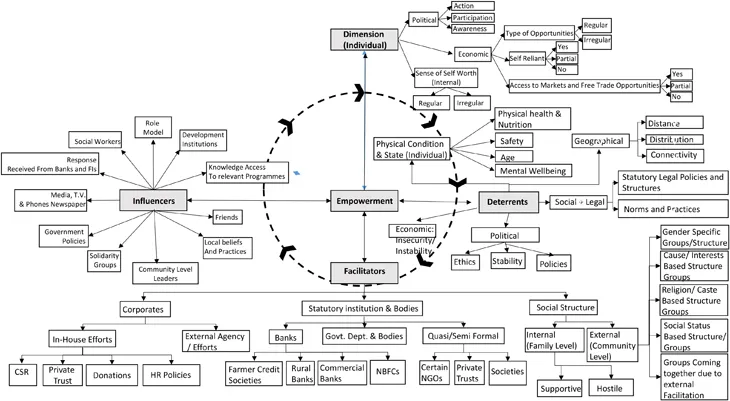

Figure 1.1 illustrates the concept of empowerment in the context of poor women in developing countries. As can be seen in this rather complex figure, empowerment has various connotations. It is the interplay of these elements or variables that impacts the individual exposed to them. The response and the resulting outcome can vary from person to person. This is because each woman is a unique individual in terms of her education, financial status, prevailing socio-economic conditions, presence or absence of support structures and the power that they wield over such an individual. There are various ‘Influencers’ such as physical and/or financial access to resources, levels of awareness of various development programmes, policies and statutory frameworks that can shape the thought process of women. The sense of self-worth may be high or low based on the stimuli received from the support structures that such a subject (woman) comes in contact with and the extent of influence exerted by them as well as the frequency of such interventions/influence.

Figure 1.1: Empowerment: Select Components and Relationships. Source: Author.

The economic position of the subject individually and in relation to a larger related group can also impact a woman. An example of this can be a situation wherein a woman is married off to an individual who may be a part of a large affluent joint family but individually may be incapable of supporting his family. In case of such a relationship, the level and frequency of influence exerted by the family head/main members on the spouse and/or her may shape the subject’s response. Facilitators of empowerment can be various business entities that can take the shape of trusts, CSR departments of large companies, donors of microfinance programmes. Facilitators can be external or internal. External entities can include formal institutions such as banks, farming and credit societies or staff welfare bodies, quasi-institutions such as NGOs, charitable trusts, NBFC-MFIs, etc. Support groups, formal or informal can help to facilitate empowerment. Deterrents can be physical inability that may be caused due to factors such as lack of proper safety, nutrition, health and care. Economic dependence can be a big deterrent. In fact, economic independence is the cornerstone that can accelerate the journey towards the goal of empowerment because reliance on an external economic provider can have an effect on the self-esteem which, in turn, can impact the ‘power within’. Other deterrents can be the geographical proximity and distribution of safe banking and financial outlets, time and cost taken to reach such destinations and the availability of affordable means of transport. Political stability, policies and environment can also have a big impact on women. The complex effect of various stimuli enumerated above can result in outcomes – which are referred to in this book as the dimensions of empowerment. Dimensions of empowerment can be further sliced into variables. These variables have been described and a theoretical model has been proposed (see Chapter 3).

Microfinance has been considered as an effective tool to combat some of the factors described in Figure 1.1, especially when it pertains to providing basic services such as savings, relatively affordable credit, skill-based training and even access to affordable medical care. It helps the poor tide over emergencies which would potentially be devastating because the poor are often left to fend for themselves in extremely difficult circumstances – particularly those that prevail in most developing economies. Grass-root-level microfinance institutions (MFIs) help to fill ‘institutional voids’ (Mair, Marti, & Ventresca, 2012). They enable to level the playing field and the ‘rules of the game’ (North, 1995), especially in cases where institutions that are supposed to facilitate inclusive growth and markets are weak (Campbell, 1990). This is important because the local institutional arrangements comprise complex intermeshing of formal rules such as constitutional rulings, property rights, government rules as well as informal rules that can influence customs, traditions, religious beliefs (Fligstein, 2001) and such rules that can constrain or enable market activity. This study presents a perspective that is based on studying Indian microfinance groups that are focused on empowering women and helping them to develop leadership qualities and find supportive peers and a framework that allows them to discover the ‘power within’.

Hence the potential of well-designed financially inclusive products, programmes and services is extremely crucial, and remains the focus of apex development and funding institutions such as the United Nations (UN), World Bank, etc. However, given the magnitude of the problem and the complexities involved due to geographical, cultural, social, linguistic variations, a large section of the needy population remain uncovered.

For example, the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs2) propagated by the UN formed a blueprint agreed to by all the world’s countries and leading development institutions. These goals ranged from halving poverty rates, providing universal access to education, to preventing the spread of HIV/AIDS by the year 2015.

Yet, in 2017 it is estimated that globally over two billion people are excluded from access to basic financial services, which in turn has an impact on the access to and the fulfilment of basic sustenance needs such as food, health & hygiene, education, housing, etc. The situation is worse in less developed countries (LDCs), where more than 90% of the population is excluded from access to the formal financial system (UN, 20063). Many of them have to depend entirely on informal sources of finance, generally at unfairly high rate of interest. It is in this context that financial inclusion4 initiatives aimed at women and managed by women assume greater importance.

Comprehensive microfinance programmes help to leverage the power of aggregation: be it in pooling and redeploying savings effectively, offering affordable health care services to the members or creating avenues for developing leadership potential and practices that can ensure sustainability. Funds received from MFIs can be used for consumption or entrepreneurial activities (Karlan & Valdivia, 2011). Some MFIs help to encourage entrepreneurial activities by providing relevant supplementary knowledge and support to help borrowers become effective entrepreneurs (Chakrabarty & Bass, 2013).

This is relevant in the light of some global trends that adversely affect poor women, such as the following.

DISPARITIES IN EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND COMPENSATION BETWEEN MEN AND WOMEN

Increasing globalisation and the resulting profit-centric approach has resulted in a spurt of work that is ‘informal’ in nature (ILO, 2002).5 Women tend to be employed in greater numbers in such sectors (in which the work is poorly paid, precarious in nature, with practically no benefits and labour protection). Globally too, the share of such unfavourable (female) employment as a percentage of employment was 52.7% for women in 2007 as compared with 49.1% for men in the same year.

CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH A GLOBALLY INTEGRATED ECONOMY: ITS ADVERSE IMPACT ON WOMEN’S ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT

A globally integrated economy has led to major changes in the scope, manner and volume of economic transactions across the world. Cut-throat competition between countries has resulted in economic policies that have led to a reduced role of the State (i.e. government) and reduced the ‘policy space’ available to the government.

Trade policies have implications for gender equality due to their impact on employment opportunities, prices and incomes. Removal of trade barriers and the consequent reduction in government collections can adversely affect social spending (Williams, 2007).

Tight monetary policies, deregulated financial markets, privatisation and licencing of new banks affect the supply of credit and its access by the lesser privileged sections of the society. Financial institutions like banks tend to favour well-established and large clients and have a commercial approach rather than a development angle in determining the availability of credit. For example, customers in urban areas with well-established documented credit histories and mortgage-backed low transaction costs may be preferred to rural customers particularly women who don’t generally have assets like land, home, etc. in their name.

There has been an increase in microfinance as a means to bridge this ‘demand–supply’ gap particularly with respect to poor women. However, it cannot compensate for the systemic failure to offer such base of the pyramid (BOP) clients an increased access and choice to a broad and comprehensive range of financial products and services.

LIMITED ACCESS OF WOMEN TO LAND, HOUSING AND OTHER PRODUCTIVE RESOURCES

The important roles performed by women in agriculture and food production is a strong reason to provide them with greater access to the land that they cultivate as well as food security (Grown, 2006). On the other hand, the negative impact associated with climate change and growing threats to sustainable development pose a greater threat for women, and place them in a particularly vulnerable position during droughts, famines or erratic rainfall patterns (IFAD, 2008).

Access to immovable property can have a positive impact on women, their families and communities on multiple fronts such as productivity gains or welfare benefits (Carlsson, 2004). In Asian countries, marriage practices, inheritance, family and communal practices impact the distribution of resources. Patrilineal norms are mostly prevalent across Asia and Africa. Such norms negate the role and importance of women family members. Some of the factors that foster inequality between men and women in terms of access and control over land resources are: unequal share of access to land at birth, discriminatory marriage norms and the patriarchal system of registering the land or the property in the name of the head of the household who is often a male (Grown, 2005).

Enforcement of laws and the availability of funds to invoke the legal process or even oppose customs that are biased is often an uphill task for women belonging to countries like India. Agarwal (1994) listed factors such as an ingrained secondary status, illiteracy, cultural norms and a fear of being ostracised as being deterrents in a woman’s ability to claim her share of rights to the property.

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING POWER

The ability of women to demand their rights such as fair wages and decent working conditions is often undermined due to their unfavourable position in the labour markets as well as a lack of a forum that can represent their collective grievances. Hence, in many parts of the world, particularly in the developing economies, women are likely to give in to the impenetrable framework of social pressures coupled with disjointed working avenues and opt to work in the unorganised or the informal sector.

Federations promoting women’s rights have helped in articulating the issues about their rights (Chikarmane & Narayanan, 2005). A spurt in the women-only trade unions in the 1990s has been attributed to the failure of the conventional unions in addressing issues affecting women. Broadbent and Ford (2007) have described the rise of three women trade unions in the Republic of Korea in 1994, to prevent and fight the exploitation of women workers in the late 1990s. Similarly the ‘Movement of Working and Unemployed Women’ was set up in Nicaragua in 1994 due to the failure of the main (male-dominated) trade union to address and voice the needs of women workers (Mendez, 2005).

ACCESS TO BASIC INFRASTRUCTURE: WATER, TRANSPORT, ELECTRICITY, ETC.

Water is an essential ingredient for survival. However, for farmers and women who are mainly engaged in agriculture, it can be associated with a lot of drudgery and effort. According to Hawkins and Seager (2010), women and children in Africa spend over 40 billion hours every year collecting water. The drudgery increases tremendously during instances of erratic weather e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Literature Review

- Chapter 3 Conceptualising Empowerment: A Theoretical Model

- Chapter 4 Nationalisation to Demonetisation: An Overview of the Indian Banking Sector

- Chapter 5 Microfinance in India – The Self-Help Group Federation and Joint Liability Models

- Chapter 6 Data and Methods

- Chapter 7 An Overview of the MFI Organisations: Annapurna Pariwar (AP) and GMSS

- Chapter 8 Observations and Discussion – Rural Area

- Chapter 9 Observations and Discussion – Urban Area

- Chapter 10 Vetale Village: Then and Now (2013–2016)

- Chapter 11 Concluding Remarks

- Appendix 1 A ‘Bad Loans’ Bank for India

- Appendix 2 Less Cash or Cashless: What about the Common Man?

- References

- Index