![]() PART I

PART I

THE CONTEXT![]()

INTRODUCTION

GOOGLE – THE GREAT DISRUPTOR

Part I of this Handbook – The Context – explores the world within which information professionals work, regardless of who employs them. The reality is one of almost continuous turbulence driven by a confluence of economic, social, and technological forces. On the economic side, the impetus for revenue growth, cost reduction, and increased profitability (i.e., productivity) must be recognized as ultimately and directly affecting both the budgets and focus of information services in a private for-profit company, a government agency, a public library, etc. On the societal front, the speed with which information is being created and shared, with little regard for its veracity, let alone with any regard for intellectual property rights, has created an environment in which there is a dwindling distinction between what is private and what is public, the ownership of information, and the accessibility of trusted information that can help us make good decisions in both our business and our personal lives.

What part does Google play in this turbulence? Google is either the savior of information professionals or their nemesis – or both – and hence deserves the label The Great Disruptor. Before Google came on the scene in 1999 and before the near ubiquitous availability of personal computers, the models of service in the information world were fairly clear. Your library/information center and you as an information professional were either a “guardian at the gate,” “an intermediary,” or a “gateway” to the myriad information resources (primarily in print) needed by your clients. Usually, all three roles came into play.

The volume of information assaulting our senses – seemingly by the nanosecond – continues to increase exponentially. The speed with which it is created and shared boggles the mind. We are knee-deep in questions about its origins, veracity, usefulness, and usability. The opportunities for information services’ (IS) expertise to address this situation abound, yet in a world where everyone fancies themselves a “researcher,” where organizations balk at investing in vetted and often expensive information resources asking “can’t you just Google-it?,” information professionals continue, generally, to be undervalued.

In 2017, it was estimated that Google held the largest market share of searches served, by far. StatCounter (March 2017) reported that as of August 2016, Google had an almost 80% market share of the top 5 search engines in the United States (Bing was the next closest at a mere 9.9%). Internet Live Stats 2017 estimated that Google processed over 40,000 search queries every second on average or over 3.5 billion searches per day and 1.2 trillion per year worldwide. By the time you are reading this, no doubt several zeros will have been added to these numbers. “Just Google it” has become as much a part of our everyday lexicon as has “Xerox it” or “Use a Kleenex.” Brand has become behavior.

Each of these initial chapters attempts to address these challenges through examining the information profession and our role in it from the broadest context of issues confronting all information professionals regardless of where they work. Whether understanding why it’s important to know about the economy at large, to how to make a business case to anticipate and navigate through the impacts of that economy, to understanding the political acumen necessary for that navigation, to figuring out where to position yourself and your services and the strategy needed to lead that kind of positioning, to recognizing 21st century challenges to organizing this new world of information, to deepening your knowledge of how to mitigate the risks around using this information and, finally to creating long-term professional sustainability, Part I provides both a theoretical underpinning and a practical approach for the student and practitioner alike.

![]()

THE ECONOMY AT LARGE AND WHY YOU SHOULD CARE

Niloufer Sohrabji

Keywords: Great Recession; information sector and services; productivity; technology diffusion

INTRODUCTION

Information services are an integral part of any organization. Information professionals are responsible for managing and using data and information. This requires expertise of various information tools and systems, an ability to access and analyze data and information (in all its formats), and have facility with current and emerging technologies. As technology improves, the demand for professionals with these skills rises. Information professionals are necessary for companies and countries to prosper, especially in this globally competitive environment.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) characterizes the information sector as one of the seven supersectors within service-providing industries1 including trade, transportation, and utilities; financial activities; professional and business services; education and health services; leisure and hospitality; and other. According to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), the information sector includes “three types of establishments: (1) those engaged in producing and distributing information and cultural products; (2) those that provide the means to transmit or distribute these products as well as data or communications; and (3) those that process data” (BLS website).

The information sector is further divided into six subsectors (BLS website). They are publishing industries; motion picture and sound recording (MPSR) industries; broadcasting; telecommunications; data processing industries; and other information services (OIS), which include archiving, library services, and internet publishing. Although the specific industries differ, all subsectors have some occupations in common such as art and media; business and finance, computer and mathematical occupations; management; and office and administrative staff. Employment is the highest in arts and media occupations for publishing, MPSR and broadcasting subsectors, while computer and mathematical occupations are the biggest employers in telecommunications, data processing, and OIS (Table 1). These occupations are related to the creation of data, information, and cultural products. Office and administrative support occupations are significant for most of these subsectors (Table 1) and together with management occupations are critical in the use of data and information. Sales and related occupations are important in telecommunications (Table 1) and are necessary for spreading the use of innovations in the larger economy.

Table 1:. Employment Data for Information Industry Subsectors (2016).

Subsector/Occupations | Employment |

Publishing | 719,090 |

Arts, design, entertainment, sports, media | 120,440 |

Business and financial operations occupations | 62,710 |

Management occupations | 64,910 |

Office and administrative support occupations | 112,570 |

Production occupations | 28,560 |

Sales and related occupations | 88,710 |

Motion picture and sound recording | 439,590 |

Arts, design, entertainment, sports, media | 176,930 |

Business and financial operations occupations | 15,790 |

Management occupations | 16,350 |

Office and administrative support occupations | 42,100 |

Broadcasting | 276,310 |

Arts, design, entertainment, sports, media | 133,860 |

Business and financial operations occupations | 14,370 |

Computer and mathematical occupations | 11,480 |

Management occupations | 23,120 |

Office and administrative support occupations | 38,040 |

Sales and related occupations | 36,110 |

Telecommunications | 775,420 |

Architecture and engineering occupations | 31,450 |

Business and financial operations occupations | 66,330 |

Computer and mathematical occupations | 130,650 |

Installation, maintenance, and repair occupations | 231,180 |

Management occupations | 35,970 |

Office and administrative support occupations | 153,090 |

Sales and related occupations | 114,540 |

Data processing and hosting | 295,990 |

Business and financial operations occupations | 30,440 |

Computer and mathematical occupations | 121,970 |

Management occupations | 28,160 |

Office and administrative support occupations | 78,560 |

Other information services | 255,690 |

Business and financial operations occupations | 27,610 |

Computer and mathematical occupations | 78,280 |

Education, training, and library occupations | 28,910 |

Management occupations | 13,960 |

Office and administrative support occupations | 40,170 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note: Data is reported for major occupations in each subsector only.

The information sector is a leader in innovation and technology. Innovation is booming in information technology and telecommunications with more than 40% of the 1.2 million patents related to these industries in 2014 (Friedman, 2015). Technological progress promotes efficiency which can have both positive and negative impacts on employment. One adverse impact is seen in the loss of jobs due to the move to web publishing and digital subscriptions (Henderson, 2015). Employment in publishing especially in newspapers, periodicals, and books has been falling for decades. From 1990 to 2016, employment in newspapers declined from 455,000 to 184,000 workers, periodicals from 146,000 to less than 94,000, and books from 86,000 to 61,000 (BLS, 2016). Some publishing (and broadcasting) has shifted to the internet, which is part of the OIS subsector with employment rising from 29,000 to 198,000 (BLS, 2016) but overall these industries have seen declines in employment.

On the other hand, innovation has led to a greater demand for information services professionals to incorporate these new products, systems, and tools in various industries and organizations. It also emphasizes the need for libraries and librarians which are a smaller but important part of OIS (Table 1). Library professionals are important in disseminating data and information to individuals and small businesses. Also, access to libraries (and museums) is an important factor in improving student achievement (Reardon, Kalogrides, & Shores, 2016). By providing resources (books and technology) and programs related to health, education, and professional development, libraries are correctly labeled the cornerstone of a healthy community.

The information sector is one of the fastest growing sectors. Output is predicted to grow by 2.9% from $1.5 trillion to over $2 trillion between 2014 and 2024 (Henderson, 2015). The report also forecasts a slight decline in employment in the sector (by 0.1%) in that same period which makes working in the sector ever more competitive. Thus, understanding the opportunities and challenges facing the United States and global economy is critical in starting and navigating one’s professional life in this sector.

This chapter provides a snapshot of the economy, understanding the long-term economic challenges facing the United States, followed by an examination of the factors that affect the information sector, and some concluding thoughts.

THE CURRENT STATE OF THE ECONOMY AND HOW WE GOT HERE

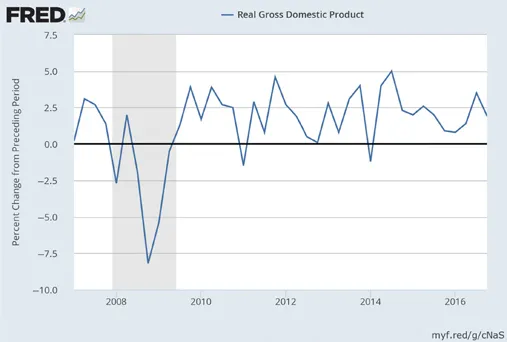

The standard statistic for measuring the health of the economy is the real gross domestic product (GDP).2 The United States faced a major recession,3 referred to as the Great Recession,4 beginning at the end of 2007. Real GDP plummeted at the end of 2007 when the housing market collapsed and started the recession with negative growth rates for all quarters between the end of 2007 and mid-2009 except for the second quarter of 2008 (Figure 1).

Figure 1:. Real GDP Growth (Annualized Quarterly). Note: The shaded area indicates the period of the Great Recession. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Real Gross Domestic Product (GDPC1). Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPC1 Accessed on April 20, 2017.

Loose monetary policy (low interest rates) during the early 2000s played a prominent role in the housing market crisis. First, low interest rates boosted demand and led to a booming housing market. Also, these low interest rates had created an incentive for investors to seek higher returns which in turn led to the creation of risky financial instruments (Origins of the financial crisis, 2013). Loans were granted to borrowers with poor credit ratings (subprime loans) with the intent of bundling these loans with others, to create low-risk securities. These securities were in turn used to back other assets (collateralized debt obligations or CDOs). Although, these financial instruments were designed to diminish risk, they encouraged risky, irresponsible, and in some cases fraudulent behavior.

This risky behavior was “tolerated” by regulators because of healthy growth and low inflation which was dubbed as “The Great Moderation” (Origins of the financial crisis, 2013). More...