![]()

CHAPTER 1

INDIGENOUS HEALTH, ENVIRONMENT, AND DISEASE BEFORE EUROPEANS

IT HAS BEEN ALMOST FIFTY YEARS SINCE AMERICAN SCHOLAR Henry Dobyns shocked the academic community with the proposition that the indigenous population of North America at contact with Europeans might have been 90 million people.1 Since then, an army of researchers has entered the fray over the true impact of Europeans on the historical trajectory of native America. Defenders of Dobyns, known in the field as “high counters,” have argued that populations could have declined as much as 95 percent as previously unseen microbes literally decimated large and vulnerable populations. Proponents of much lower population losses have vilified Dobyns and his adherents, even mocking demographic estimates as “Numbers from Nowhere.”2 Although scholars would probably agree that the severity of population decline and the suffering unleashed on the indigenous people of America were unprecedented, those seeking a precise quantitative resolution to what has been described as an “American Holocaust” on estimates of number of dwellings and number of people within them will probably never come to a satisfactory conclusion. Sadly, the limits of archaeology and the passage of centuries will keep us from ever going beyond informed speculation about the size of the indigenous population on a continental scale and having a full account of the population decline as a consequence of their encounter with Europeans and their microbes.

Although their work has been largely overshadowed by the fight over the magnitude of the horror unleashed by Columbian encounter, researchers have made great strides in the understanding of health and disease in prehistoric North America. Three decades ago Jane Buikstra’s edited volume Prehistoric Tuberculosis in the Americas showed beyond a doubt that tuberculosis was endemic to the New World, present long before the arrival of Europeans.3 In addition to TB, prehistoric populations were subject to a host of diseases, including hepatitis, polio, intestinal parasites, encephalitis, arthritis, pinta, Chagas’ disease, and American leishmaniasis, a disease of the skin and mucous membranes caused by parasites.4 We know that North America was not a disease-free paradise before the arrival of Europeans. Advances in both historical climate change and archaeology are contributing to new and perhaps unsettling insights into the changes across much of the continent in the centuries before Columbus.

A stark example can be found in the small community of Crow Creek, South Dakota. Sometime after the turn of the fourteenth century, 500 people, already suffering from malnutrition, were killed and mutilated, their community burned around their bodies and their bones left exposed to scavengers.5 Soon a new village was built by the invaders on top of the killing grounds.6 The carnage at Crow Creek was but one manifestation of the hardship experienced across the northern hemisphere resulting from an intense climatic downturn that began in the mid-thirteenth century.7 Across the eastern half of the continent, from the Arctic to the Mississippi Delta, indigenous societies experienced profound disruption and significant decline in their population as their way of life became unsustainable in the new and unforgiving climate regime. For many societies, the depth and duration of harsh conditions and the resulting social disruptions might have meant that their peak populations did not occur on the eve of the first introduced epidemics but might actually have occurred centuries earlier.

Before the upheaval of the thirteenth century, societies on both sides of the Atlantic had experienced four centuries of growth and development fuelled by favourable climatic conditions equivalent to those of the 1960s. Depending on the geographical region, the period is known variously as the “Climatic Optimum,” the “Medieval Warm Period,” the “Medieval Climatic Anomaly,” or the “Neo-Atlantic Climatic Episode.”8 In North America, 400 years of good weather reshaped both the natural and the human landscapes of the continent. In the far north, the Thule ancestors of the historical Inuit expanded from Alaska to Greenland, hunting whales from large boats in the open water of the Arctic Ocean and living in villages of stone houses while Norse settlers planted cereal crops in Greenland.9 For the northern Great Plains and the adjacent forests, archaeologists David Meyer and Scott Hamilton described the climate during this period simply as “benign.”10

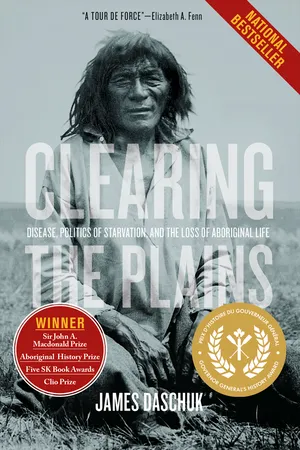

Crow Creek bone bed. Courtesy of the University of South Dakota Archaeology Laboratory.

In the halcyon years between 800 and 1200 CE, societies from the Atlantic to the Dakotas revolutionized their food base as they added the horticultural triumvirate of corn, beans, and squash to their diets.11 Archaeologically, the people who spread the technology, and taste, for corn and its related crops are known as Late Woodland cultures.12 The heart of the vast cultural and economic network that spread through the eastern half of the continent was the metropolis of Cahokia, a city of as many as 20,000 people in 1100 CE.13 Its large population, surpassed only by that of Philadelphia at the end of the eighteenth century, and its huge earthen mounds, mark it as the apex of social organization and social stratification in prehistoric North America.14

From Cahokia and other centres near the confluence of the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers, farming spread quickly to Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, where it was adopted by the Siouan-speaking Oneota people.15 Farther north the addition of corn-based horticulture to hunting and wild rice harvesting propelled the expansion of a people known to archaeologists as Blackduck from the boundary waters region to the interlakes of Manitoba to the shores of Lake Superior, where they lived alongside the Laurel people of the Canadian Shield.16 Around 1000 CE, a hybrid group, called the Rainy Lake Composite, developed from their Laurel and Blackduck neighbours. The new group might have been the ancestors of the historical Anishinabe or Ojibwa people.17 To the west, the ancestors of the Siouan-speaking Mandan and Hidatsa were establishing “semi-sedentary” villages in North and South Dakota along the Missouri River, where they added gardening to their traditions of hunting and gathering.18 The most northerly of these villages was only 200 kilometres south of the forty-ninth parallel.

The horticultural wave that swept across the eastern half of the continent during the Neo-Atlantic Climate Episode stopped abruptly at the Missouri villages, though long-distance trade networks brought corn as far north as the Carrot River near the lower Saskatchewan River and other locations across the boreal forest of central Canada.19 Archaeologist Dale Walde has shown that climate was not the limiting factor in the westward march of cultivation. Communities that continued to specialize in bison hunting did so because their material needs were more than adequately met.20 Walde asserted that prehistoric populations on the Canadian plains, rather than small, nomadic, band-level societies, were large, sophisticated, “tribally” organized communities made up of as many as 1,000 individuals working communally to produce “an almost industrial level of resource exploitation.”21 These large groups provided enough labour to drive herds over large distances and then kill and process them, creating large surpluses of food that were traded (often for corn and other crops) or stockpiled for future use. Food surpluses gave communities time to pursue quests for more than just food, developing formal institutions within them based on age, gender, or expertise. Instead of roaming the plains in search of food, these communities were semi-sedentary, remaining in place for as long as six months at a time, alternating between river valley complexes and the open plains.22 Because these communities were pedestrian, with only dogs as beasts of burden, the distance between winter and summer residences was probably not more than a walk of a few days.

The good conditions of the Neo-Atlantic Climate Episode contributed to the long-term build-up of the biomass of the region, in turn reinforcing the well-being and stability of bison-hunting communities on the northern plains. Before 1000 CE, only two distinct technological traditions were present on the Canadian plains. Archaeologists refer to them as the Besant and Avonlea phases.23 Besant sites first appeared on the eastern plains of Minnesota about 200 BCE. Makers of Avonlea technology first appeared in the arid southern plains of Alberta and Saskatchewan three centuries later. Avonlea sites are so widespread that Walde cautioned that their makers should not be thought of as a people or single ethnicity; instead, they were probably from a variety of ethnic backgrounds sharing technology—especially the bow and arrow—as a sign of “mutual support,” perhaps in the face of Besant encroachment from the east.24 By the turn of the first millennium, a new tradition called Old Woman’s emerged in southern Alberta. The makers of Old Woman’s technology are acknowledged to be the ancestors of the historical Niitsitapi or Blackfoot people. Over time, they gradually replaced Avonlea in the region.25

The end of the centuries-long period of growth, development, and stability came swiftly and brutally. Hemispheric conditions changed so rapidly that they have been attributed to a single cataclysmic event, a huge volcanic explosion in 1259 CE.26 Recent scientific scholarship has recognized volcanism as a trigger for abrupt, large-scale climate change and that “LIA (Little Ice Age) summer cold and ice growth began abruptly between 1275 and 1300 AD. …”27 Jared Diamond has shown that, when confronted with environmental challenges such as those that came with the deteriorating climate of the late thirteenth century, the choices made by communities were the difference between success and oblivion over the long term. In Greenland, rigid adherence to unsustainable European farming practices marked the beginning of the end for Norse settlement, while their indigenous neighbours shifted their subsistence strategies across the arctic, adapting to the harsh conditions and surviving in the long term.28 Far to the south, societies that had grown and prospered with the adoption of corn and related crops were especially hard hit. Some, like the horticultural villages of New York State and southern Quebec, came together after several generations of conflict and privation to form the League of the Iroquois, a sophist...