![]()

Chapter 1

Wanting to Know

Indian Residential School

At age six I suddenly found myself inside the fence surrounding the playground of Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School (QIRS),1 crying as my mother, Lucy, and stepfather, Lou, drove away, leaving me to begin my stay at the imposing red-brick school in the small town of Lebret in southern Saskatchewan. The school building rose four storeys—a structure with the unmistakable appearance of an institution. However, before long, friendly boys came over and pulled me away to play. Playing with other boys created one bright spot of life at QIRS. One of our favourite pastimes was “cowboys and Indians,” where we mimicked what we saw on television. Cowboy and Indian westerns seemed to be on all the time in the late 1950s. Indians always attacked futilely while cowboys heroically fought them off. We especially liked the Lone Ranger because he had an Indian sidekick, Tonto. But all the Indian kids wanted to play the cowboy. We could easily pull the trigger of the imaginary gun and watch others playing the Indians fly off their pretend ponies into gritty dirt. After a while, the “Indians” got tired of always dying and demanded to become the “cowboys.” It was an example of how we lacked an understanding of our past.

Austerely robed Catholic clergy who operated the school imposed their frightening views of God and heaven and the devil and hell on their charges. Walking through the door into our classroom, we were met with “Lacombe’s Ladder,” a large chart especially created for residential schools. It showed two paths: on one, converts strode happily and confidently on a path towards heaven; on the other, sinister-looking Indians wearing traditional clothing meandered down a road leading to a place marked “hell,” complete with fire and staffed by devils.2 The view of the world offered did not satisfy my sense of what constituted right or wrong. The explanations given about God and heaven and hell did not seem to make a lot of sense. The portrayal of Indian characters did not match the kindness of mosôms and kohkoms (grandmothers) I knew. But, as young children, we complied with what we were told.

We prayed incessantly: upon waking; before and after breakfast, dinner, and supper; before and after class time; then a group rosary in the evening; and finally a bedtime prayer. There was Mass every Sunday and on other special days. Like many boys, I rose early to serve as an altar helper to hold wine for the priest at Mass.

One thing that stayed with me during my time at Indian residential school was the memory of how I sat on the swing in the schoolyard and observed traffic going down the road beside the school. I contemplated why the world appeared the way it did and what everything was “all about.” I wondered why we Indian children lived in what amounted to prison-like conditions, confined to the schoolyard and subjected to an extremely regimented existence. This included ruminations about the nature of existence. Accounts by the priests seemed to lack something. I could not understand why there was no better explanation for the physical world and why we as humans existed. I convinced myself that there had to be something beyond what was obvious to the senses and I had to know what that was.

In retrospect, I realize I always had a strong curiosity about, and desire to pursue, knowledge. I loved to learn about the kings and queens of England and once created an elaborate class project on Robin Hood, including a castle. I avidly absorbed information in books, whether about history or geography or science.

My mother, Lucy, reassured my siblings and me that residential school was a good place where I could have three square meals a day, structured activity, and the opportunity to learn and get ahead in the world. I was very fortunate to have an older brother, Gerry, and two older sisters, Bernice and Sharon, who also attended QIRS. Mom and my stepfather would come to visit us every other week. I always looked forward to leaving the confines of school for a couple of hours.

Unfortunately, some of my classmates heard from relatives that it was a prison for Indian youth, and, as a consequence, they devoted much of their time and energy to rebelling or running away. When we look at the history of Indian residential schools, there is no question that the whole purpose of the schools was to undermine our understanding and perception of our self and our community. Yet, by the time I attended in the 1950s, the harshest of practices had ended. I did not at first believe Elders who told me some children had spent the entire twelve months of the year in school. In fact, until the 1920s, that was exactly what occurred.3

Some kids had a harder time adjusting to a routine of class, chores, structured and supervised recreation, and the constant round of prayers. Students often got into trouble over small things. One time, a friend and I wanted to have a cool “duck tail” hairstyle like the bigger boys and so we used butter to smooth down our hair. Another time, four of us decided to raid the food pantry on the main floor. We snuck out of bed and crept downstairs to get outside, then crawled through a window into the kitchen. The night watchman on his patrol of the dormitory somehow got wind of our absence and caught us red-handed!

For those who stepped out of line, punishment inevitably followed. After bedtime prayer, when everybody knelt by their beds to mouth a quick utterance before diving into bed, we would wait to see if anyone was going to get the dreaded strap. The dorm itself held nearly a hundred beds, lined up in four long rows. The punishment ritual began with the miscreant’s being summoned to the supervisor’s room down the hall from the main dormitory. Next, we would hear a couple of whacks of the strap, followed by bellows of crying. The victim came out scurrying to his bed. I got that treatment for the escapade of stealing cookies. The unhappiest kids would wait for the earliest opportunity to escape, and every once in a while word spread that “so and so” had run away. Usually, the escapee was forcibly returned after some days and put under close watch, detention, and more punishment.

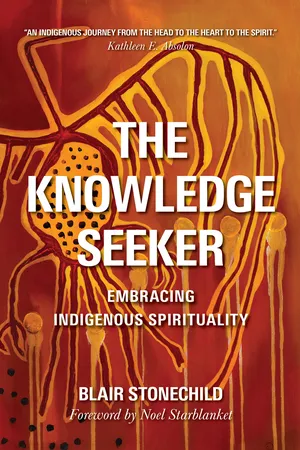

Author at Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School, 1963.

Despite the strict regime, I was reasonably content in residential school, partly by virtue of having older relatives, making me less of a target for schoolyard bullies. I feared them more than the authorities. My dear mother wisely reinforced the message that school was a good place to learn and to get three meals a day. Moreover, coming from a broken home, I found at school a stability I might not have had otherwise. Fortunately, at my mother’s request, I was allowed to visit the Métis side of my family, who lived in the town of Lebret. This meant the world to me, as it alleviated the weight of residential school, and I looked forward to being warmly welcomed by my Métis kohkom, Celina.

I perceived school staff for the most part as being decent people, but nevertheless aloof authority figures, so close loving relationships were lacking. The reality of residential schools is that it severed relationships with family, with community, with culture, with past, and with identity, and in that sense became an extreme form of cultural genocide.4 Among the litany of ills identified by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada is the erasure of the Aboriginal spiritual world view.

As I entered grade nine in 1965, Indian residential schools began closing down. Because I was deemed a promising student, the principal took steps to recommend where I should go to continue my education. I was sent to Campion High School, a Jesuit-run high school for boys in Regina, the capital city of Saskatchewan. It was a challenge adapting to a highly competitive environment, but I fervently believed that education was worth the effort and would be a ticket to a better life. There were embarrassing moments when, as the sole Indian in the high school, references were made inferring the savagery of Indian people. Although the majority of white students were welcoming, a few picked on me because of my heritage. However, I did not succumb to such negative portrayals because my mosôm and kohkom and other relatives, although they had little formal education, were the kindest, most hospitable, and compassionate people one could ever meet. Campion did not expect a lot of me, as I was initially placed in the “slow room.” But, with diligent studying, I progressed to become one of the students with the highest grades. By grade twelve I was sufficiently popular to be chosen by my peers to be editor of our high school newspaper. My friend Ron, who was in charge of the yearbook, wrote under my picture the caption: “Blair wants to be Prime Minster of Canada—will put all white people on reserves.” But, by the time the good priests had finished editing, the caption read simply: “Wants to be Prime Minister.” The teachers obviously didn’t think much of our sense of humour!5

After nine years at Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School and three years at Campion High School, my desire for learning only became stronger. That led me to apply to, and be accepted at, McGill University in Montreal, one of the most outstanding universities in Canada. I believed that post-secondary education was a right Indians secured by virtue of Treaties and therefore that the Department of Indian Affairs covered all costs of attending. When I approached Indian Affairs, however, they said I had no choice but to attend the closer University of Saskatchewan. Not willing to give in so easily, I threatened not to go to university at all. My plan to attend McGill was accepted.

University and Activism

In 1969 I started in the engineering program at McGill. Moving to cosmopolitan Montreal was quite a breath of fresh air after the stifling racism I and all Indian youth experienced in Regina. But, even in Montreal, it didn’t take long to find ignorance. While I was staying at a McGill residence during my first year, another resident asked me in all sincerity whether Indians still lived in teepees and hunted buffalo in Saskatchewan.

There were only about 125 Canadian Indians enrolled in universities across the country at the time. The 1960s were an exciting period marked by social change, and challenges against oppressive assimilation policies towards Indians were in the offing. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau had announced his unilateral policy to terminate First Nations rights—a move intended to lead to total assimilation. Indigenous political leaders quickly scrambled to organize and assert their rights.6 Walter Deiter of Saskatchewan became the first elected national chief of the fledgling National Indian Brotherhood (now Assembly of First Nations).

I attended my first activist event at McGill—a teach-in on Indigenous rights organized by Iroquois graduate student George Miller that featured articulate advocate Harold Cardinal, who was the university-educated leader of the Indian Association of Alberta and author of The Unjust Society, a groundbreaking declaration of First Nation grievances.7 Although I passed all my engineering classes, with all the activism going on, I decided to switch my major from engineering to political science. I realized my interest in Native rights had more personal meaning.

The wealthy Montreal businessman McKay Smith arranged through Westmount Rotary Club to purchase a house on Selkirk Street as a residence for Native students. It became an informal gathering place for the handful of First Nations students, including Roberta Jamieson, Denis Gaspe, and others who went on to successful careers. By coincidence, legendary Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin8 lived across the street and gave us additional encouragement. In my university classes I...