![]()

Chapter 1

Mind Control—Internal or External?

1.0 CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Classical cognitive science adopts the representational theory of mind (Pylyshyn, 1984). According to this theory, cognition is the rule-governed manipulation of internal symbols or representations. This view has evolved from Cartesian philosophy (Descartes, 1637/1960), and has adopted many of Descartes’ tacit assumptions about the nature of the mind (Devlin, 1996). For example, it views the mind as a disembodied entity that can be studied independently of its relationship to the world. This view of the rational mind as distinct from the world has also been used to distinguish humans from other organisms. That is, rational humans are viewed as being controllers or creators of their environment, while irrational animals are completely under the environment’s control (Bertalanffy, 1967; Bronowski, 1973; Cottingham, 1978).

The purpose of this chapter is to explore this view of the mind, in preparation for considering alternative accounts of cognition that will be developed in more detail as the book proceeds. We begin by considering the representational theory of mind, and how it is typically used to distinguish man from other organisms. We consider examples of animals, such as beavers and social insects, that appear to challenge this view because they create sophisticated structures, and could be viewed to some degree as controllers or builders of their own environment. A variety of theories of how they build these structures are briefly considered. Some of these theories essentially treat these animals as being rational or representational. However, more modern theories are consistent with the notion that the construction of elaborate nests or other structures is predominantly under the control of environmental stimuli; one prominent concept in such theories is stigmergy. The chapter ends, though, by pointing out that such control is easily found in prototypical architectures that have been used to model human cognition. It raises the possibility that higher-order human cognition might be far less Cartesian than classical cognitive science assumes, a theme that will be developed in more detail in Chapter 2. The notion of stigmergy that is introduced in Chapter 1 will recur in later chapters, and will be particularly important in Chapter 8’s discussion of collective intelligence.

1.1 OUR SPECIAL INTELLIGENCE

We humans constantly attempt to identify our unique characteristics. For many our special status comes from possessing a soul or consciousness. For Descartes, the essence of the soul was “only to think,” and the possession of the soul distinguished us from the animals (Descartes, 1637/1960). Because they lacked souls, animals could not be distinguished from machines: “If there were any machines which had the organs and appearance of a monkey or of some other unreasoning animal, we would have no way of telling that it was not of the same nature as these animals” (p. 41). This view resulted in Cartesian philosophy being condemned by modern animal rights activists (Cottingham, 1978).

More modern arguments hold that it is our intellect that separates us from animals and machines (Bronowski, 1973). “Man is distinguished from other animals by his imaginative gifts. He makes plans, inventions, new discoveries, by putting different talents together; and his discoveries become more subtle and penetrating, as he learns to combine his talents in more complex and intimate ways” (p. 20). Biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy noted, “symbolism, if you will, is the divine spark distinguishing the poorest specimen of true man from the most perfectly adapted animal” (Bertalanffy, 1967, p. 36).

It has been argued that mind emerged from the natural selection of abilities to reason about the consequences of hypothetical actions (Popper, 1978). Rather than performing an action that would have fatal consequences, the action can be thought about, evaluated, and discarded before actually being performed.

Popper’s position is central to much research in artificial intelligence and cognitive science. The fundamental hypothesis of such classical or symbolic research is that cognition is computation, that thinking is the rule-governed manipulation of symbols that represent the world. Thus the key role of cognition is planning: on the basis of perceptual information, the mind builds a model of the world, and uses this model to plan the next action to be taken. This has been called the sense–think–act cycle (Pfeifer & Scheier, 1999). Classical cognitive science has studied the thinking component of this cycle (What symbols are used to represent the world? What rules are used to manipulate these symbols? What methods are used to choose which rule to apply at a given time?), often at the expense of studying sensing and acting (Anderson et al., 2004; Newell, 1990).

A consequence of the sense–think–act cycle is diminished environmental control over humans. “Among the multitude of animals which scamper, fly, burrow and swim around us, man is the only one who is not locked into his environment. His imagination, his reason, his emotional subtlety and toughness, make it possible for him not to accept the environment, but to change it” (Bronowski, 1973, p. 19). In modern cognitivism, mind reigns over matter.

Ironically, cognitivism antagonizes the view that cognition makes humans special. If cognition is computation, then certain artifacts might be cognitive as well. The realization that digital computers are general purpose symbol manipulators implies the possibility of machine intelligence (Turing, 1950): “I believe that at the end of the century the use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted” (p. 442).

However, classical cognitivism is also subject to competing points of view. A growing number of researchers are concerned that the emphasis on planning using representations of the world is ultimately flawed. They argue that the mind is not a planner, but is instead a controller that links perceptions with actions without requiring planning, reasoning, or central control. They would like to replace the “sense–think–act” cycle with a “sense–act” cycle in which the world serves as a model of itself. Interestingly, this approach assumes that human intelligence is largely controlled by the environment, perhaps making us less special than we desire. The purpose of this book is to explore this alternative view of cognition.

1.2 RODENTS THAT ENGINEER WETLANDS

1.2.1 Castor canadensis

Is our intelligence special? Perhaps the divide between ourselves and the animals is much smaller than we believe. Consider, for example, the North American beaver, Castor canadensis. A large rodent, a typical adult beaver usually lives in a small colony of between four and eight animals (Müller-Schwarze & Sun, 2003). Communication amongst animals in a colony is accomplished using scent marks, a variety of vocalizations, and the tail slap alarm signal (Figure 1-1).

1-1

In his classic study, Lewis Morgan noted that “in structural organization the beaver occupies a low position in the scale of mammalian forms” (Morgan, 1868/1986, p. 17). Nonetheless, the beaver is renowned for its artifacts. “Around him are the dam, the lodge, the burrow, the tree-cutting, and the artificial canal; each testifying to his handiwork, and affording us an opportunity to see the application as well as the results of his mental and physical powers” (p. 18). In short, beavers — like humans — construct their own environments.

1-2

To dam a stream (Figure 1-2), a colony of beavers will first prop sticks on both banks, pointing them roughly 30° upstream (Müller-Schwarze & Sun, 2003). Heavy stones are then moved to weigh these sticks down; grass is stuffed between these stones. Beavers complete the dam by ramming poles into the existing structure that sticks out from the bank. Poles are aligned with stream flow direction. The dam curves to resist stream flow; sharper-curved dams are used in faster streams. Beavers add mud to the upstream side of the dam to seal it. The dam is constantly maintained, reinforced and raised when water levels are low; it is made to leak more when water levels become too high (Frisch, 1974). Dams range in height from 20 cm to 3 m, and a large dam can be several hundred metres in length. A colony of beavers might construct more than a dozen dams to control water levels in their territory.

1.2.2 The Cognitive Beaver?

How does such a small, simple animal create these incredible structures? Morgan attributed intelligence, reasoning, and planning to the beaver. For instance, he argued that a beaver’s felling of a tree involved a complicated sequence of thought processes, including identifying the tree as a food source and determining whether the tree was near enough to the pond or a canal to be transported. Such thought sequences “involve as well as prove a series of reasoning processes indistinguishable from similar processes of reasoning performed by the human mind” (Morgan, 1868/1986, pp. 262-263). If this were true, then the division between man and beast would be blurred. Later, though, we will consider the possibility that even though the beaver is manipulating its environment, it is still completely governed by it. However, we must also explore the prospect that, in a similar fashion, the environment plays an enormous role in controlling human cognition.

1.3 THE INSTINCTS OF INSECTS

To begin to reflect on how thought or behaviour might be under environmental control, let us consider insects, organisms that are far simpler than beavers.

1.3.1 The Instinctive Wasp

Insects are generally viewed as “blind creatures of impulse.” For example, in his assessment of insect-like robots, Moravec (1999) notes that they, like insects, are intellectually damned: “The vast majority fail to complete their life cycles, often doomed, like moths trapped by a streetlight, by severe cognitive limitations.” These limitations suggest that insects are primarily controlled by instinct (Hingston, 1933), where instinct is “a force that is innate in the animal, and one performed with but little understanding” (p. 132).

This view of insects can be traced to French entomologist J.H. Fabre. He described a number of experiments involving digger wasps, whose nests are burrows dug into the soil (Fabre, 1915). A digger wasp paralyzes its prey, and drags it back to a nest. The prey is left outside as the wasp ventures inside the burrow for a brief inspection, after which the wasp drags the prey inside, lays a single egg upon it, leaves the burrow, and seals the entrance.

While the wasp was inspecting the burrow, Fabre moved its paralyzed prey to a different position outside the nest (Fabre, 1919). This caused the wasp to unnecessarily re-inspect the burrow. If Fabre moved the prey once more during the wasp’s second inspection, the wasp inspected the nest again!

In another investigation, Fabre (1915) completely removed the prey from the vicinity of the burrow. After conducting a vain search, the wasp turned and sealed the empty burrow as if they prey had already been deposited. “Instinct knows everything, in the undeviating paths marked out for it; it knows nothing, outside those paths” (Fabre, 1915, p. 211).

1.3.2 Umwelt and Control

The instincts uncovered by Fabre are not blind, because some adaptation to novel situations occurs. At different stages of the construction of a wasp’s nest, researchers have damaged the nest and observed the ensuing repairs. Repaired nests can deviate dramatically in appearance from the characteristic nest of the species (Smith, 1978). Indeed, environmental constraints cause a great deal of variation of nest structure amongst wasps of the same species (Wenzel, 1991). This would be impossible if wasp behaviour were completely inflexible.

However, this flexibility is controlled by the environment. That is, observed variability is not the result of modifying instincts themselves, but rather the result of how instincts interact with a variable environment. Instincts are elicited by stimuli in the sensory world, which was called the umwelt by ethologist Jakob von Uexküll. The umwelt is an “island of the senses”; agents can only experience the world in particular ways because of limits, or specializations, in their sensory apparatus (Uexküll, 2001). Because of this, different organisms can live in the same environment, but at the same time exist in different umwelten, because they experience this world in different ways. The notion of umwelt is similar to the notion of affordance in ecological theories of perception (Gibson, 1966, 1979).

Some have argued that the symbolic nature of human thought and language makes us the only species capable of creating our own umwelt (Bertalanffy, 1967). “Any part of the world, from galaxies inaccessible to direct perception and biologically irrelevant, down to equally inaccessible and biologically irrelevant atoms, can become an object of ‘interest’ to man. He invents accessory sense organs to explore them, and learns behavior to cope with them” (p. 21). While the animal umwelt restricts them to a physical universe, “man lives in a symbolic world of language, thought, social entities, money, science, religion, art” (p. 22).

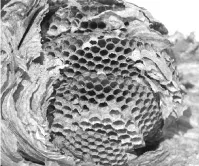

1.4 PAPER WASP COLONIES AND THEIR NESTS

Experiments have revealed the instincts of solitary wasps (Fabre, 1915, 1919) and other insects. However, social insects can produce artifacts that may not be so easily rooted in instinct. This is because these artifacts are examples of collective intelligence (Goldstone & Janssen, 2005; Kube & Zhang, 1994; Sulis, 1997). Collective intelligence requires coordinating the activities of many agents; its creations cannot be produced by one agent working in isolation. Might paper nests show how social insects create and control their own environment?

1.4.1 Colonies and Their Nests

For example, the North American bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata, which is not a hornet but instead a wasp) houses its colony in an inverted, pear-shaped “paper” nest. A mature nest can be as large as a basketball; an example nest is illustrated in Figure 1-3.

1-3

1-4

Inside the outer paper envelope is a highly structured interior (Figure 1-4). There are several horizontal layers, each consisting of a number of hexagonal combs. A layer of combs is attached to the one directly above it, so that the layers hang as a group from the top of the nest. Each comb layer is roughly circular in shape, and its diameter and shape match the outer contours of the nest. The walls of each comb are elongated, some being longer than others.

“In the complexity and regularity of their nests and the diversity of their construction techniques, wasps equal or surpass many of the ants and bees” (Jeanne, 1996, p. 473). There is tremendous variability in the size, shape, and location of social wasp nests (Downing & Jeanne, 1986). A nest may range from having a few dozen cells to having in the order of a million; some wasps build nests that are as high as one metre (Theraulaz, Bonabeau, & Deneubourg, 1998). As well, nest construction can involve the coordination of specialized labor. For example, Polybia occidentalis constructs nests using builders, wood-pulp foragers, and water foragers (Jeanne, 1996).

1.4.2 Scaling Up

The large and intricate nests constructed by colonies of social wasps might challenge simple, instinctive, explanations. Such nests are used and maintained by a small number of wasp generations for just a few months. Greater challenges to explaining nest construction emerge when we are confronted with other insect colonies, such as termites, whose mounds are vastly larger structures built by millions of insects extending over many years. Such nests “seem evidence of a master plan which controls the activities of the builders and is based on the requirements of the community. How this can come to pass within the enormous complex of millions of blind workers is something we do not know” (Frisch, 1974, p. 150). Let us now turn to considering termite nests, and ask whether these structures might offer evidence of cognitive processes that are qualitatively similar to our own.

1.5 THE TOWERS OF TERMITES

1.5.1 Termite Mounds

Termites are social insects that live in colonies that may contain as many as a million members. Though seemingly similar to bees and ants, they are actually more closely related to cockroaches. In arid savannahs termites are notable for housing the colony in distinctively shaped structures called mounds. One of the incredible properties of termite mounds is their size: they can tower over the landscape. While a typical termite mound is an impressive 2 metres in height, an exceptional one might be as high as 7 metres (Frisch, 1974)!

Termite mounds are remarkable for more than their size. One issue that is critical for the health of the colony is maintaining a consistent temperature in the elaborate network of tunnels and chambers within the mound. This is particularly true for some species that cultivate fungus within the mound as...