Why do you want to be a book editor? One of the reasons many people are attracted to book editing is the allure of authors. What editor wouldn’t want to meet the next J.K. Rowling, an up-and-coming Margaret Atwood, a Joyce Carol Oates in the making? Another attraction is the physicality of books themselves and what they contain. Around the globe, humans have invested books with a special significance, both for the ideas they present and for the cultural values they represent.

What Is a Book?

Simply put, books are storehouses for information and narratives of various kinds—whatever a culture deems to be valuable. Books as objects have existed for several thousand years, although not always in forms that people today would recognize as “books.” For our purposes today, a book is a gathering of sheets bound together in some manner (such as by sewing or with glue) and protected by a COVER , possibly including a spine; this definition of book reflects the codex, which dates from the early Common Era. The codex is what most people think of when they visualize a book, and it is to the codex that most people refer when we contemplate the concept of “bookness,” or an object’s likeness to a generic book structure.

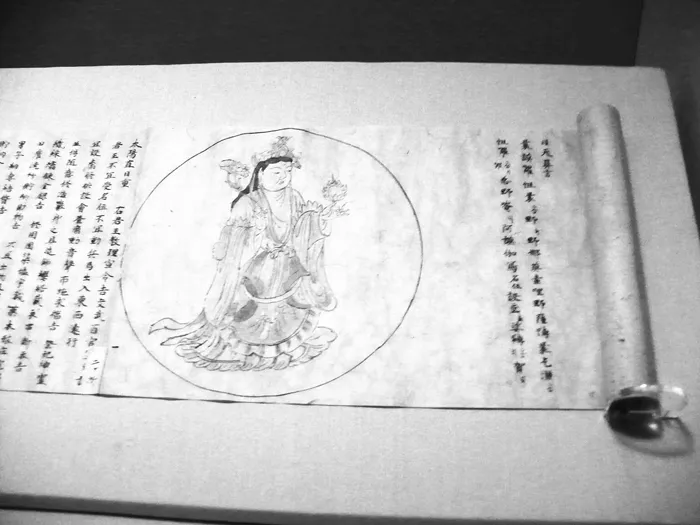

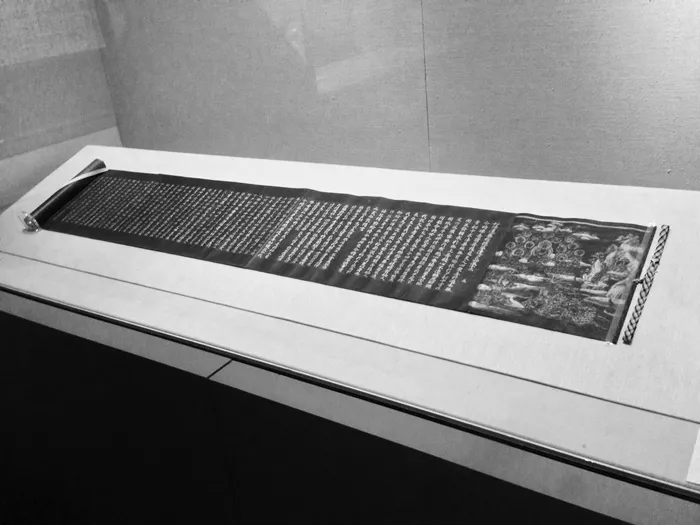

Prior to the development of the codex, and for centuries after it, too, books were produced in the form of scrolls. The significance, and advantage, of moving toward the codex and away from the scroll is that the codex made documents more durable (because the covers protected the contents), made them easier to store and transport (because flat is more convenient geometry than round), and allowed greater ease of use (because a codex can be opened at any point randomly, while a scroll must be rolled from beginning to end to be useful). Prior to the scroll, we might look to collected and numbered clay tablets such as the Sumerians made—but perhaps that stretches our modern sense of “book” too far.

Yet whether we consider a collection of clay tablets a “book” or not is relevant today, when many commentators argue that the experience of consuming text from a screen is qualitatively different from consuming text from bound paper—that is, that an ebook isn’t a “book” because of how it is used, regardless of the text it contains. For many people, the physical object of the book—the paper, glue, and ink—is what matters, not the structure of the text or its provision of information or story. People who read ebooks often respond to the evocation of the paper book with a strongly defensive tone; ebook readers are frequently accused of disliking books, or of not being “real” readers, whatever that may mean. And we might look to the way in which dedicated ereading devices have been manufactured to emulate the experience of conventional book-in-hand reading—a clear evocation of bookness. What a book is—and relatedly, what kinds of reading are valuable and what kinds are not—is a highly contentious question at this moment in our society, as we stand ready to embrace, or reject, the transformation of the book in a digital world.

Questions of what is and is not a book—much like questions of what is and is not publishable—depend on privilege and authority: who gets to decide? That notion is something you should keep in mind as you work through this text: books are a technology of privilege. For most of human history, most people could not write or read; and until the last few decades, the ownership of multiple books was restricted to a relatively small group of people. Even today, many millions of people in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other Western nations cannot afford to own books. That there are books in so many formats that we can argue about them—that there are books to edit at all—is an outcome of our society’s tremendous privilege, something we ought not to take for granted.

A book is both a physical and an abstract thing. Many writers are encouraged by the notion that they have a book in them—in which case we are obviously not talking about a physical glue-and-paper object. And most of us would distinguish “our” books—the books we personally own and cherish—from the masses of other people’s books, as well as from the unpurchased books stocked in bookstores. Digital books add a new dimension to our mutable sense of the book—although some people would say digital books also erase elements of the book. Since the late nineteenth century, scholars have been studying books as objects that transmit specific information about a culture and its meanings, examining the process of manufacturing, circulating, reading, and preserving both books in general and specific EDITIONS and specific copies of individual titles. For instance, reading a cheap “student” edition of a book versus a fine limited edition may, perhaps, change our experience of the text it contains—or perhaps not. Our preferences as readers should never be cast as “wrong” or “better,” but they deserve to be investigated because they tell us important things about ourselves as individuals and as a society. If all the elements of publication are successful, readers should ideally lose themselves in the book’s content, experiencing the physical book almost invisibly, yet the physical book is still there. Our preferences and judgements for and against various editions precede and emerge from our actual experiences of reading and using text. As book editors, we have these experiences of text ourselves and in turn produce them for others.

My purpose in this text is more practical than academic, but you should keep these points in mind. The book as the West has known it for some five hundred years is changing, and these changes are pushing Western society to ask important questions about who we are, how we communicate, and what we value. Books represent a portable visual record of information and narrative for future generations—but somehow that’s not all they are, either, even from the most crassly commercial point of view.

Why a Book?

Books have history. From the earliest days of cuneiform (an ancient system of writing) to the monks copying pages in scriptoria, through the advent of moveable type to today’s digital formats, books have formed a significant part of human culture. The reception of books changes over time, and some ages of human society have been less friendly to books and writing than others; still, written texts have endured over centuries, even over millennia. In the Western world, books engage and inform our legal, political, and moral organization—and of course are informed by these forces in turn.

Books also have permanence. Unlike newspapers or magazines, which are intended to be disposable, most books are intended to be lasting physical forms. Medieval books, constructed prior to the rise of moveable type, were often precious objects, written on fine vellum, ornamented with illumination, and decorated with ivory, gems, and other luxury materials. (Medieval textbooks, by the way, were not ornamented or decorated; in fact, according to book history scholar Erik Kwakkel, their proportions and page design were similar to those found in contemporary textbooks, but they were much less colourful.) As books and other printed objects became more common in the early modern era, the cost of books dropped; by the nineteenth century, books were often produced in inexpensive, if inelegant, editions affordable to almost anyone. In the twentieth century, shelves displaying rows and rows of books became a standard feature of the middle-class home, and continue to be a fixture of today’s interior design. The shift from physical to digital formats, however, is affecting our idea of a book’s permanence and even changing how we “own” books.

The Role of Librarians

As we think about books’ history and permanence, we should consider the role of libraries and librarians. For thousands of years, specialized workers have collected, catalogued, maintained, and circulated written text and other information cultures value, and it is through this work that we now have copies of some of humanity’s most ancient texts. Libraries play an important role—sometimes unintentionally—in determining the books that are preserved and those that are forgotten. In the late nineteenth century, alongside the rise of public schooling, public libraries were founded with the express intent of offering people the opportunity to better themselves through almost unlimited access to information. By the early twentieth century, many librarians had become champions of books and the freedom to read, and libraries became the physical representation of this belief. Today, libraries continue to collect, organize, and circulate books, as well as periodicals, DVDs, video games, toys, and even seeds; and increasingly, libraries provide portals to digital texts, including ebooks and streaming music.

While you may not think of libraries when you think of the role of the book editor, libraries remain an important—and sometimes challenging—SALES CHANNEL for most publishers. Some book editors, particularly those publishing materials for children and teens, think carefully about libraries’ values and technical practices as the editors make their acquisitions decisions. For instance, if a manuscript contained subject matter or language that might discourage in-school or community librarians from buying the finished book, some editors would be wary of acquiring that manuscript.