![]()

I. The Agency Strategy: How Congress Impedes Executive Branch Cost-Cutting Objectives

Too often Congress mires itself in the parochial, or myopic, concerns of its individual members at the expense of broader national goals and interests. This excessive preoccupation with local impact, which we call the parochial imperative, frequently prevents the executive branch from achieving cost savings and efficiencies that could be of benefit to taxpayers and our nation as a whole. Too often when the executive branch proposes a national strategy or plan to solve a systemic problem, Congress invokes the parochial imperative and micromanages the plan until it no longer represents a viable national solution.

When the Carter administration proposed a nationwide plan to reduce the costs of water projects, Congress subjected it to such rigorous parochial scrutiny that only miniscule savings were achieved. When, beginning in the 1960s, a succession of administrations attempted to enact a national strategy for closing inefficient and costly military bases, Congress resisted and eventually so ham-strung the executive branch with legislative restrictions that unneeded, budget-draining bases are still being operated in large numbers. When the Ford administration proposed a nationwide reevaluation of military commissaries to decrease the taxpayer subsidy, Congress refused to make any change in the status quo.

The cumulative impact of parochial-based decisions is an almost complete freeze on the size, structure, and management strategies of government. Congress has offered no broad cost-cutting solutions of its own, so it is the taxpayers who suffer the consequences.

National Water Policy: "Playing to the Parochial Imperative"

Forty miles south of Kansas City, Kans., the Hillsdale Dam rises 75 feet above the placid waters of Hillsdale Lake, which was created by the dam. On a pleasant sunny afternoon the waters are dotted with tiny triangles of white and crisscrossed by the curving wakes of sailboats, powerboats, and the boats of folks just out fishing.

Very likely Joe and Jane Mainstreet are out there, using one of the two free boat ramps to get their craft into the water. Nearby is a public visitor center. All in all this is a very nice place to spend a quiet holiday, and apparently free of charge.

Hillsdale Dam and Lake make up one of 3,422 water development and flood-control projects built or being built, at a total federal investment of over $36 billion, since Congress authorized the first Rivers and Harbors Act in 1824. Completed in 1982 at a cost of $61.2 million, nearly 5.5 times its original estimate of $9.4 million, the Hillsdale project today is a relatively small monument to one of the fiercest legislative battles Congress has fought to preserve its parochial interest at the expense of a national perspective.

The fight, which began barely a month after Jimmy Carter was inaugurated as president in 1977, continued for nearly two years and did not end until he had to exercise a veto. It is worth examining in detail because it illustrates, in rare fashion, the elements that make up the clash between parochial and national needs.

From the earliest days of the Republic, Congress has considered the development of water resources a special part of its own political domain. Congress traditionally has approved each decision to undertake such projects as a Hillsdale Dam and Lake, including its detailed specifications. And each year, through the annual public works appropriations bill (recently renamed the energy and water development appropriations bill), Congress doles out precise amounts of money for the planning, design, and construction of these projects. Because every project is precisely located, and thus precisely local, the interests of affected representatives and senators is always an integral part of this particular governing process. As a result each project is evaluated on a case-by-case basis, on its own merits. Through this perhaps not intended, much less planned for, piecemeal approach, Congress has formulated what in the end has become the nation's water resources policy.

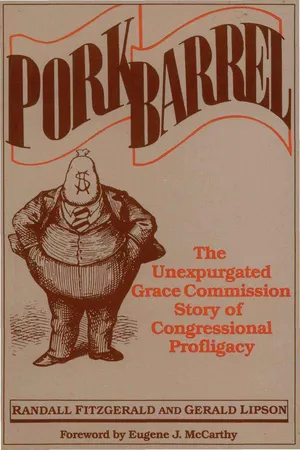

In the course of his 1976 bid for the White House, then former governor Jimmy Carter campaigned as both a conservationist and a fiscal conservative. Among other things he pledged to halt the construction of unnecessary and environmentally destructive dams and to generally reform what then passed for national water resources programs. In essence he promised to put a lid on the pork barrel.

Well before inauguration day, a transition team was preparing to redeem that pledge, reviewing a broad range of projects that had been included in the 1978 public works budget submitted to Congress by President Ford shortly before he left office.

Every newly elected president seeks to make his mark as soon as possible. The first opportunity usually comes by seeking revisions in the last federal budget submitted by an outgoing predecessor. There is a long overlap between the federal budget cycle and the beginning of each new presidential term of office. The federal fiscal year begins on October 1, but the president must by law submit his proposed budget for that fiscal year the preceding February, thus giving Congress eight months to consider the president's agenda in light of its own priorities.

Each presidential budget itself is the culmination of a process that runs for well over a year, beginning with estimates of spending requirements and proposals in executive agency offices that work their way through cabinet-level decisions to the Office of Management and Budget and ultimately to the president.

Thus, a newly elected president enters office with several years of his first (and perhaps only) administration already programmed by a predecessor. He takes office four months into a fiscal year that began a full month before the election he won. At the same time the budget for the fiscal year that will begin when the new administration is eight months in office already has been submitted to Congress, obviously reflecting the spending priorities of the preceding administration. About the only way a new president can begin to show immediate action on the budget is to propose changes in the one just submitted to Congress.

On February 22, 1977, President Carter announced his intention to reevaluate about 300 of the 506 water resource projects that were in President Ford's FY 1978 budget, with an eye to deleting those that no longer made economic or environmental sense. At the same time Carter named a number of projects for which he said he already was inclined to end funding. Many of the projects approved in the past "under different economic circumstances and at times of lower interest rates are of doubtful necessity now, in light of new economic conditions and environmental policies," he said.

Within a day of the president's statement, members of Congress were blistering him for attempting to "usurp" their traditional prerogatives. So began a running battle between the executive branch and Congress that, although it rose and dipped in intensity, did not end until the near close of the 95th Congress. Even members with national reputations as supporters of the environment and as budget cutters joined the chorus once it appeared their states or districts were affected.

Rep. Morris K. Udall of Arizona, chairman of the House Interior Committee and known as a strong environmentalist, took sharp issue with President Carter's questioning of the $1.3 billion Central Arizona Project, a massive and controversial undertaking to divert water from the Colorado River for use in central and lower Arizona. Calling the president's decision "very hasty," Udall said it was like "pronouncing a verdict of guilty before the trial."

Two other representatives with reputations as fiscal conservatives, Eldon Rudd of Arizona and Mickey Edwards of Oklahoma, said the cuts smacked of an "imperial Presidency." Within two days Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus was before Chairman Udall's committee insisting that "there have been no permanent decisions" as yet.

The fact that a $900 million dam in California would be sited in an earthquake zone, while a $436 million reclamation project in North Dakota was souring relations with Canada, did not deter members of Congress from those states from defending the projects and attacking the president for proposing to delete them from the budget.

The congressional heat was so intense that within days President Carter began to back away. On February 28, less than a week after the announcement, Florida Governor Reuben Askew, then chairman of the National Governors Conference, reported that the president had assured a group of Western governors that he was not prejudging disposition of any projects then under review.

Finally, on April 18, President Carter announced he would formally ask Congress to delete from the 1978 public works appropriations bill funding for 18 projects, for a saving of $177.4 million, or 1.7 percent of the 1978 budget of $10.2 billion proposed for energy and water development for the coming fiscal year. Total savings, should the projects be canceled entirely, would amount to $2.5 billion.

Charged with shaping the 1978 public works bill in the House was Tom Bevill, a six-term congressman from Alabama's fourth district, an area with a strong populist tradition. Bevill reflected the philosophy that government should spend liberally on public works and in the process provide public service jobs. He had just assumed chairmanship of the Public Works Appropriations Subcommittee, and few expected him to begin his tenure by cutting projects willingly. Of the 18 cuts sought by President Carter, Bevill's subcommittee agreed to one, a project near Topeka, Kans., at a budgetary saving of $1 million for the year. The cut was considered so marginal that even the member in whose district the project was located declined to defend it.

So, as the 1978 public works bill headed for the House floor, the initial response by Congress to a request by the president for a $177.4 million spending cut was to give him $1 million of it. With signals flying that Congress was not going to cooperate on the water projects issue, the first hints of a presidential veto began to be heard. A veto is the ultimate legislative weapon that a president has against the Congress. It takes two-thirds of those present and voting in both legislative bodies to override a veto.

A veto may sound like a strong threat, but the pressure of practical politics requires a president to weigh its use very carefully. For one thing a veto is all or nothing, involving the entire measure sent to the president for his signature. Unlike the governors of 43 states who have authority to veto specific items in a bill while accepting others (the so-called line-item veto), the president of the United States has no such choice. Thus the veto, though powerful, is clumsy.

President Carter would have to reject the entire $10.2 billion bill just to eliminate 18 projects worth less than 2 percent of the measure. In the process he also would very likely upset members concerned about parts of the bill that had nothing to do with the matter at issue, but that would still suffer the same veto.

Even as the bill was moving toward the House floor, a move to cut the 17 projects still in it was being planned by Rep. Silvio O. Conte of Massachusetts, ranking minority member of the House Appropriations Committee. Conte, whose district spans the hills, valleys, woods, and small towns of the Connecticut Valley, is known as an outdoorsman with a respect for the natural environment. He has clashed frequently with colleagues and administrations over what he considers wasteful and environmentally harmful water projects. As one of 72 representatives and senators who had signed a letter to President Carter on February 14 expressing support for his efforts to "reform the water resources program," Conte was prepared to back the president as far as he could. He teamed up with Rep. Butler C. Derrick, Jr. of South Carolina to offer an amendment on the House floor to knock out 17 "boondoggle" water projects. The odds were heavily against their success.

The House Appropriations Committee is divided into 13 subcommittees, each of which exercises jurisdiction over specific agencies and functions of the federal government. These subcommittees hold almost exclusive and unchallenged sway over their domains, with most of the spending decisions being worked out among the members ...