- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In his new book, Poverty and Progress: Realities and Myths about Global Poverty, renowned development economist Deepak Lal draws on 50 years of experience around the globe to describe developing-country realities and rectify misguided notions about economic progress. Unique among books that have emerged in recent years on world poverty, Poverty and Progress directly confronts intellectual fads of the West and dismantles a wide range of myths that have obscured an astounding achievement: the unprecedented spread of economic progress around the world that is eliminating the scourge of mass poverty.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Poverty and Progress by Deepak Lal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

REALITY

1. The Ascent from Mass Poverty

In thinking about poverty, it is useful to make a distinction between three types: structural, conjunctural, and destitution.

The first—mass structural poverty—is what most concerns observers. It is the type that underlies the numbers calculated by various national and international agencies of the absolute poor—globally and in particular countries. Given the endowments of land, labor, and capital, and the existing technology, if per capita income is so low that any redistribution of income will merely lead to a redistribution of poverty, rather than its alleviation, mass structural poverty can only be eliminated by rapid economic growth.

By contrast, destitution and conjunctural poverty1 require income transfers for amelioration if their sufferers are to survive. The major difference between these types of poverty is that while destitute individuals have no means of making a living and hence must receive permanent income transfers to survive, the conjunctural poor need temporary transfers, since their poverty is caused by climatic fluctuations (as is common in agrarian economies) or the trade cycle (in industrial economies) and can be expected to end with the upturn in the weather or the economy. These transfers can be from either private donors or the government, though much of the passion in continuing debates concerns the latter.

Ancient Mass Structural Poverty

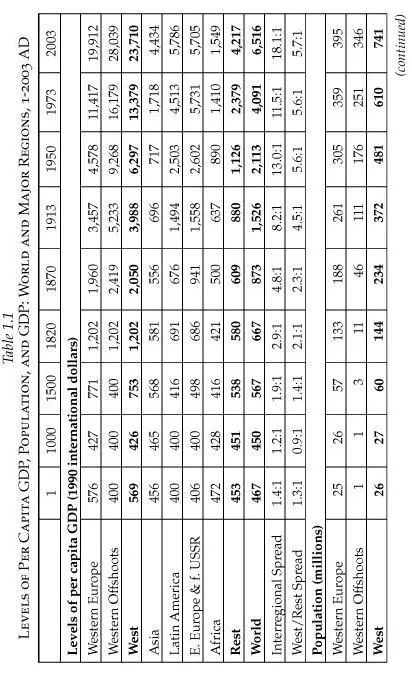

Table 1.1, which summarizes Angus Maddison’s estimates of the level of per capita income in different regions of the world (and separately for India, China, and Japan) from 1–2003 AD, shows that for most of human history until 1000 AD, the per capita income of the world and most of its regions was about $450 in 1990 purchasing power dollars per year. As the internationally accepted absolute poverty line is roughly $1 per day, this suggests that the level of income of someone at the poverty line would be $365 per year. Given the pervasive social stratification in Eurasian agrarian economies, with a small upper crust of merchants, priests, and warriors having a higher income than the peasants whose labor provided the surplus to keep them in relative luxury, the mass of the population would have been at or below the poverty line. Thus for most of human history, mass structural poverty has been the norm.

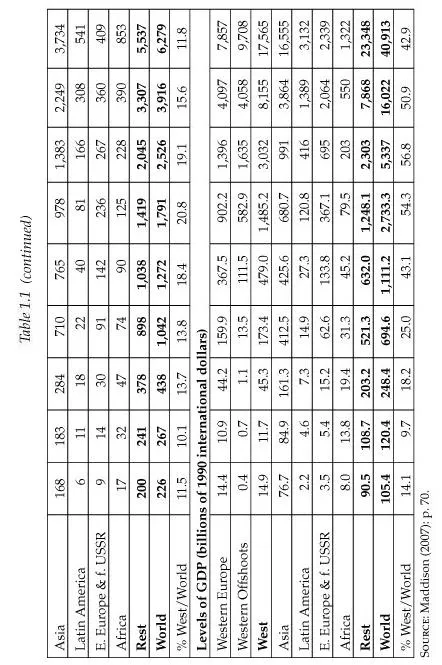

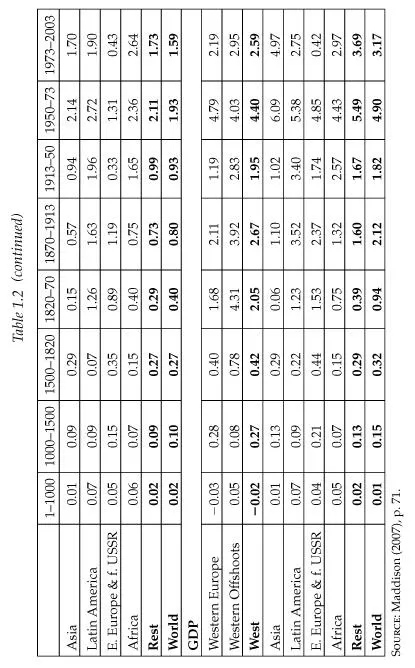

Growth did occur in these premodern agrarian economies (see Table 1.2), but it was the extensive kind, with output expanding with population as new land was brought into cultivation, but leaving the per capita income virtually constant.

But even in these Eurasian agrarian economies there were periods of intensive growth, with output expanding faster than the population. This rise in per capita income was usually associated with the rise of empires. They enlarged the common economic space by integrating hitherto autarkic regions into a common market, leading to gains from trade and the division of labor emphasized by Adam Smith, as well as from technological exchanges. The increase in per capita income from this Smithian intensive growth, however, could not be sustained, as the economy reverted to a long period of extensive growth with a higher per capita income. With their climacteric, these imperial agrarian economies remained in equilibrium at a relatively high level. Only recently have the two major ones (India and China) begun generating unbounded Promethean intensive growth.

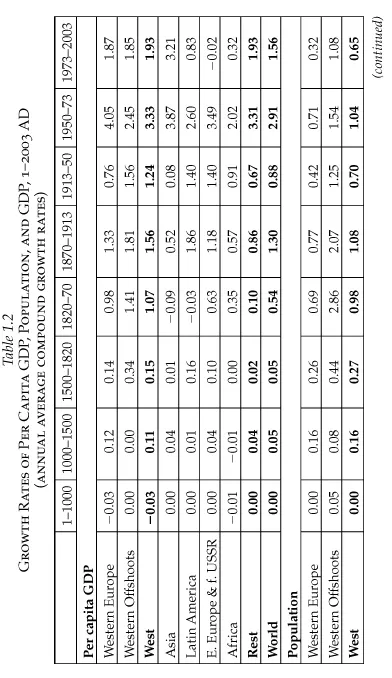

Table 1.3 shows the data for the three dominant Eurasian imperial systems in 0 AD—Rome, China, and India. Of these, only the two Asian imperial “states” survive to our day. Indian per capita income was probably the highest, since it had reached its climacteric with the imperial unification of the subcontinent by the Mauryas in the sixth century BC. Thereafter, per capita income stagnated because only extensive growth occurred until the British Raj introduced the first whiff of Promethean growth in the 19th century.

China did not experience its climacteric till the Sung unified the lands of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers in the 11th century, leading to a higher per capita income equilibrium than in India. China then entered a prolonged period of extensive growth, with output expanding in line with the steady increase in its population. Rome reached its climacteric during the reign of Augustus in the first decades of the Christian century, when its imperial expansion ended. With the fall of the western empire to the barbarians in 476 AD, western Europe saw a steep fall in its living standards as economic disorder replaced the order provided by the Roman imperium. It did not reach the Augustan standard of living till the 16th century (Lal 2004).

Table 1.3

GDP AND POPULATION FOR ANCIENT POWERS, 0 AD

GDP AND POPULATION FOR ANCIENT POWERS, 0 AD

| GDP (in millions of 1990 U.S. dollars) | Population (in thousands) | GDP per capita | |

| Roman Empire | 20,961 | 55,000 | 381 |

| China | 26,820 | 59,600 | 450 |

| India-1 | 33,750 | 75,000 | 450 |

| India-2 | 55,146 | 100,000 | 551 |

SOURCES: Maddison (2001), pp. 241, 261, 264; Goldsmith (1984). Tons of gold converted into U.S. dollars at the average 1990 price; Lal (1989); 1965 dollars converted into 1990 dollars using GDP deflator.

The Rise of Capitalism

This slow western ascent began with the creation of an institution unique in the ancient Eurasian civilizations—capitalism. Though definitions of capitalism are still contested by social scientists, most of these conflate the existence of its agents—merchant capitalists—and instruments—markets, bill of exchange, banks, etc.—with the institution that arose only in the 11th century. Capitalists and their instruments have existed since at least 2000 BC in all the ancient Eurasian civilizations, as testified by Mesopotamian tablets of the Karum. But capitalists’ property rights remained insecure. It was only when they were finally protected from the predations of the state that the institution of capitalism arose in one part of Eurasia in the 11th century (Lal 2006). I have argued in Unintended Consequences that this was due to two papal revolutions. A brief account of this emergence of capitalism follows.

Merchant capitalists were a necessary “evil” in all the ancient agrarian civilizations because of the social stratification that emerged for two major reasons. First, all the ancient Eurasian civilizations were centers of the sedentary agriculture practiced in the river valleys where they arose. But they were constantly under threat from two sets of nomadic roving bandits: from the Steppes in North Asia and the deserts of Arabia. Unlike the inhabitants of the settled agrarian communities, these nomads had not eschewed the predatory and warlike ways of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. They mounted periodic raids on the rich sedentary civilizations. To protect these riverine agrarian civilizations, wielders of the sword became a necessity (Lal 2004). These warriors sought to extend the boundaries of their states to naturally defensible borders, creating imperial polities—and these warriors needed to be fed.

This provides the second reason for Eurasian social stratification. In the ancient world (unlike much of Eurasia today), land was abundant, but people to work it were scarce. This meant that if attempts were made to tax peasants, implicitly or explicitly, they could flee these predations. It was necessary to tie them down to the land. Various institutions like serfdom, slavery, and the caste system were devised to achieve this aim, allowing an agricultural surplus to be extracted to feed the warriors who lived in towns (Lal 2005a). To justify these various forms of social control, “people of the book” (priests) arose to provide the cosmological beliefs that underwrote these civilizations. Thus social stratification of the wielders of the sword, the keepers of the book, and the yeomen of the plow emerged in all these Eurasian civilizations.

There was also the need to move the agricultural surplus from the villages to the towns, where the soldiers and priests lived. This service was provided by merchants and traders—the ancient capitalists. In the process, many of them became very rich. But their wealth was insecure, being subject to periodic raids by the predatory state. Nor was this predation unpopular. As risk takers and novelty seekers, these capitalists were seen as dangerous to the settled ways of stable agraria...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables, Figures, and Boxes

- Introduction

- Part I: Reality

- 1. The Ascent from Mass Poverty

- 2. The Global Spread of Well-Being

- 3. Destitution, Conjunctural Poverty, and Income Transfers

- 4. Political Economy

- Part 2: Myths

- 5. The Numbers Game

- 6. Statistical Snake Oil

- 7. Theoretical Curiosities

- 8. Micro Everything

- 9. Saving Africa

- 10. Global Warming

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography