![]()

1. Introduction

Your health is in constant peril from exposure to a multitude of toxic chemicals. Or so it seems, as frequent media reports alert us to the dangers of eating alar-treated apples, drinking artificially sweetened coffee, ingesting certain laxatives, swimming in backyard pools, and pumping automotive gasoline (Ingersoll 1998; McGinley 1997b; McGinley 1997a; Halpert 1995).

Each new warning generates an almost predictable public debate (Passell 1995; Kelly 1995; Cushman 1997; Kenney 1998). First, interventionists demand stricter government regulations to reduce our exposure to the new health risk. Pragmatists counter that the costs of such controls will swamp whatever benefits they might offer. Skeptics question the underlying study’s scientific validity and advocate waiting until better knowledge is obtained. Finally, the cautious wonder if uncertainty can excuse failing to protect the public health.

How are we to sort through all the rhetoric that surrounds questions of science and health?

Further scientific research will provide only limited answers to only some of the questions. Better studies can reduce—but not eliminate—our uncertainty about chemical side effects. Policymakers still will have to face tough decisions.

In general, policy analysts examine sources of conflict in a market society and determine what the government might do to improve firm and consumer choices. This book examines the specific issue of chemicals in our modern industrial society and discusses how government can enhance public health. In this context, important policy issues include:

How well does the market for synthetic chemicals operate?

Are individuals and firms making efficient choices about chemical use and exposure?1

Are choices concerning chemical use and exposure subject to value or equity conflicts?2 If so, how should such disputes be resolved?

Although, under certain circumstances, an enlightened government theoretically could improve the efficiency of chemical markets, does government intervention suffer from “government failure” and, thus, not produce improvements (Stigler 1971; Posner 1974; Peltzman 1976; Becker 1983; Shepsle and Weingast 1984; Wolf 1993; Keech 1995)?

Chapter 2 examines the current state of scientific research into how chemical exposures affect human health. There are good human studies on only a few substances. Animal and bacterial studies are more plentiful but are a poor substitute. Furthermore, better research will contribute surprisingly little to many chemical exposure disputes, which involve equity conflicts and trade-offs falling in the realm of policy analysis.

Chapter 3 focuses on those chemical exposure risks that are private goods.3 Individuals can choose to avoid dangers like pesticide-laden food by paying extra for pesticide-free food. But they can properly weigh risks only if they know the harmful effects of these chemicals. Unfortunately, citizens who obtained sufficient information through the market would have little time to do anything else. Courts enhance the operation of markets with common-law torts, but no single liability rule efficiently manages all chemical risks in all situations. Government bureaucracies attempt to enhance the operation of markets, but their one-size-fits-all command-and-control regulations are very flawed.

Chapter 4 discusses chemical risks that are public goods.4 Risks like air pollution are collectively consumed, and individuals generally cannot avoid them simply by acquiring information and making choices. While torts and regulations theoretically can produce efficient levels of public exposure, they usually fall short.

Regardless of what institutions govern human exposure to chemicals, residual exposure will exist. Risk-averse individuals will want to share that risk through insurance. Chapter 5 explains the operation of insurance markets, particularly environmental insurance markets. The federal “Superfund” program and certain court decisions have made insurers reluctant to write environmental insurance contracts. Until Congress and the courts stop confiscating wealth through arbitrary statutes and common-law decisions, the environmental liability insurance market will not work well.

Chapter 6 reviews the findings and makes policy recommendations. Conflicts about exposure to chemicals involve three value or political choices involving consent and property rights. First, who decides whether false-positive (declaring a safe substance to be harmful) or false-negative (declaring a harmful substance to be safe) errors are more costly? Second, should some citizens be taxed to augment the ability of others to purchase information about the effects of exposure? Third, what liability rules should govern the manufacture and sale of chemicals?

In the case of chemical exposures that are private goods, government should provide information rather than regulation. And the negligence liability rule, rather than strict liability, should be applied.

For collective exposures, government should create ambient quality standards to achieve the same cost-versus-health balance observed in private market decisions. The government should then auction emissions property rights to the highest bidders and distribute the proceeds to all citizens equally.

![]()

2. Effects of Synthetic Chemical Exposures on Human Health

Exposure to synthetic1 chemicals, like any other activity, can be analyzed by using a cost-benefit framework. Rational individuals consume private goods if benefits exceed costs.

Consumers can easily calculate the benefits of chemical use. Farmers compute how pesticides increase crop yields, and people appreciate the fact that chlorination produces bacteria-free water. It is more difficult to determine the costs of chemical use because, in addition to a commodity’s market price, there are less obvious costs, such as increased health risks.

This chapter surveys the scientific literature and explains what is known about chemical exposures and human health.

Issues of Statistical Inference

Suppose we wanted to determine if a new drug reduces insomnia. We could conduct an experiment in which some subjects were exposed to the drug and compare their insomnia rate with that of a control group who were not exposed.

If 2 of the 20 people in the exposed group reported insomnia (10 percent) and 3 of the 20 people in the control group reported insomnia (15 percent), we might attribute the 5 percent difference to the drug. But we could not be certain. The drug could have had no effect on sleep. Perhaps 5 of the 40 people in the experiment were insomniacs to begin with, and 3 of them just happened to be assigned to the control group.

But we could boost our confidence by increasing the size of the groups. If there were 1,076 people in each group and we observed a 5 percent incidence difference, then we could be 95 percent certain that the drug had a positive effect.2

What if the drug’s effect were not so noticeable? Suppose we observed only a 1 percent incidence difference in our experiment? With 1,076 people in each group, we could be only 63 percent confident that exposure to the drug caused a decrease in insomnia. To be 95 percent confident, we would need nearly 27,000 subjects in each group. To detect differences of 0.1 percent with 95 percent confidence requires 2.9 million subjects in each group. No one has ever conducted such a study because of the extraordinary expense.3

Given practical limits, we can detect only differences of at least 1 percent. Fortunately, drug effects are usually relatively large. But the increased cancer risks that concern regulatory authorities and many citizens are relatively small4—usually much smaller than the level of risk that scientists confidently can distinguish from “background noise” (Kaldor and Day 1985, 79).5

Why 95 Percent Confident?

Researchers usually decide how much an exposed group must differ from a control group before attributing the difference to the exposure rather than to mere sampling variation around a “true” result of no difference. Many scientists do not feel comfortable saying an exposed group differs significantly from a control group unless there is less than a 5 percent probability that the difference could have arisen through sampling variation.6 The 5 percent figure is no more magical than 4 percent or 6 percent; it is simply convention.

Researchers can make two types of probabilistic inference errors: false positive and false negative. In human health research, false-positive errors occur if health differences between the two groups in a study are deemed the result of substance exposure even though the average result of repeated studies would show no health difference. False-negative errors occur if the opposite happens—that is, health differences between two groups in a study are deemed the result of sampling variation even though the average result of repeated studies would show a real health difference.

More specifically, a false-positive error occurs if it is wrongly concluded that a safe chemical causes cancer. A false-negative error occurs if it is wrongly concluded that a carcinogen is safe.

A troubling aspect of probabilistic error is that, for a given sample size, reducing the likelihood of one type of inference error increases the likelihood of the other type. If false-positive errors are minimized, false-negative errors are dramatically increased and vice versa. As we shall see, only by increasing sample size can we decrease the probability of one type of inference error while holding the other type constant.

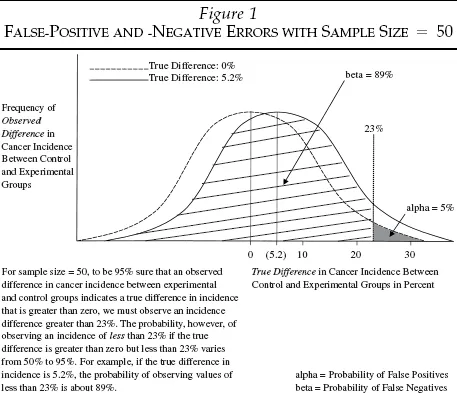

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate how the determination of false-positive and -negative inference errors varies with sample size. In Figure 1, the sample size is 50. To be 95 percent confident that an observed incidence difference between the experimental and control groups is really evidence of carcinogenicity rather than sampling variation, the difference in cancer rates between the two groups must be at least 23 percent.

Limiting false-positive errors to 5 percent, however, increases the likelihood of false negatives. Assume, for instance, that the true incidence difference in the example shown in Figure 1 is 5.2 percent. To keep false positive errors to less than 5 percent, all differences of less than 23 percent are deemed too small to be the result of exposure. If the true difference in cancer incidence is, in fact, 5.2 percent, the probability of erroneously concluding that a substance is not a carcinogen is more than 89 percent.7

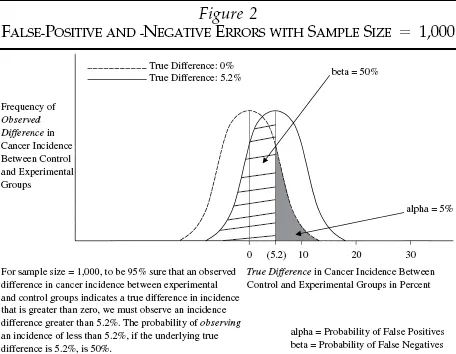

Figure 2 shows the same analysis for a sample size of 1,000. To keep false-positive errors below 5 percent, we must observe incidence differences of only 5.2 percent instead of 23 percent. Let us again assume the true incidence difference is 5.2 percent. The probability of finding an incidence difference of less than 5.2 percent and erroneously exonerating a carcinogen now is only 50 percent instead of 89 percent.

What About False-Negative Errors?

Critics correctly argue that most scientists worry more about false positive errors than about false negatives. That concern inevitably increases false-negative errors (Green 1992; Latin 1988), and we incorrectly exonerate many carcinogens.

As the actual truth gets closer to the null hypothesis (e.g., an incidence difference of 0 percent) and farther from the 5 percent false-positive critical value (e.g., 23 percent in Figure 1), the probability of false-negative errors approaches 95 percent.8 On the other hand, the probability of false-negative errors approaches 50 percent as the actual truth gets farther from the null hypothesis and closer to the 5 percent false-positive critical value.9

For any given sample size, there is a zero-sum trade-off between false negatives and false positives. But as we increase the sample size, the 5 percent false-positive critical value shrinks, and the true incidence difference gets closer to the new critical value and relatively farther from the null hypothesis. Thus, the probability of false negatives is reduced while the probability of false positives remains constant. Notice that in the examples presented in Figures 1 and 2, with an assumed truth of 5.2 percent cancer incidence difference and a constant 5 percent probability of false-positive errors, the probability of false-negative errors fell from 89 to 50 percent as the sample size rose from 50 to 1,000.

Optimal Emphasis on False Positives or False Negatives

The choice between false-positive and -negative errors is a choice involving costs and benefits, like any other choice; not surprisingly, people disagree about the trade-offs.10 Some people believe that, in matters of public health, we should care about false negatives much more than false positives. That is, we should worry about the possibility of a substance causing cancer much more than the benefits lost if a substance is wrongly labeled a carcinogen and its consumption declines. Others take the opposite viewpoint. How should we evaluate such views?

Chapter 3 argues that when chemical exposure is a private good, people can decide for themselves how to weigh the costs and benefits of erring in either direction. No public or private entity needs to decide the “correct” trade-off. In fact, no “correct” trade-off exists. Chapter 4 notes that matters become more complicated when we can collectively consume only one level of ambient exposure.

Summary

A generic problem in all studies of the effects of chemical exposures on health is the need to differentiate “real” effects from random “background noise.” Statistical variance in an experiment can result in a safe substance’s being declared hazardous. And vice versa.

This causes two problems in cancer-risk policy. First, because the public (and, hence, policymakers) worries about small levels of increased cancer risk resulting from chemical exposures, the number of subjects required to differentiate small risks from zero risk is enormous, which makes the studies prohibitively expensive. Second, there is an important (but usually unstated) conflict over the relative importance of false-positive and false-negative errors. Although scientists are the main participants in this debate, we must resort to extrascientific values to resolve it.

Exposure Effects Obtained from Humans

Drug Trials and Their Limitations

A drug trial exposes randomly selected humans to varying doses of a chemical and compares their subsequent health with the health of randomly selected subjects who were not exposed. Researchers perform such true experiments because the potential benefits of determining a drug’s effectiveness offset the drug’s possible dangers. But in many cases scientists cannot use true experiments to study chemical effects on human health: ethical considerations prevent them from intentionally exposing people to chemicals that probably do more harm than good (National Research Council 1991; Green 1992). Instead, they attempt to mimic the precision of true experiments with alternative methodologies.

Case-Control and Convenience-Cohort Studies

In the commonly used retrospective case-control study, “cases” (e.g.,...