![]()

Natural Monopoly and Its Regulation

A firm that is the only seller of a product or service having no close substitutes is said to enjoy a monopoly.1 Monopoly is an important concept to this Article but even more important is the related but somewhat less familiar concept of "natural monopoly." The term does not refer to the actual number of sellers in a market but to the relationship between demand and the technology of supply. If the entire demand within a relevant market can be satisfied at lowest cost by one firm rather than by two or more, the market is a natural monopoly, whatever the actual number of firms in it. If such a market contains more than one firm, either the firms will quickly shake down to one through mergers or failures, or production will continue to consume more resources than necessary. In the first case competition is short-lived and in the second it produces inefficient results. Competition is thus not a viable regulatory mechanism under conditions of natural monopoly. Hence, it is said, direct controls are necessary to ensure satisfactory performance: controls over profits, specific rates, quality of service, extensions and abandonments of service and plant, even permission whether to enter the business at all. This set of controls has been applied mainly to gas, water, and electric power companies, where it is known as "public utility regulation," and to providers of public transportation and telecommunications, where it is known as "common carrier regulation." (I shall use "regulation" or "public utility regulation" to refer to both.) The question that this Article addresses is whether natural monopoly provides an adequate justification for the imposition of these regulatory controls.2

A critical examination of this question seems timely. The terms "public utility" and "common carrier" may have rather an antiquering, but they also have important contemporary applications. The regulated industries provide the essential infrastructure of modern industrial society. They are also on the frontiers of technological progress. The principal civilian use of nuclear energy has been electrical generation, the principal commercial application of space technology satellite communications; both are regulated services. We are also witnessing the emergence of immensely promising industries, such as cable television, that may have sufficient natural monopoly characteristics to invite extension of the regulatory principle to them. And it is even intimated that the extension of price controls to the economy at large must be seriously considered.3

As a perusal of the citations in this Article will disclose, the 1960's have .seen an upsurge of scholarly interest in the regulatory field after many years of comparative neglect. The Brookings Institution is supporting an ambitious program of study in the field. Several high-level federal policy groups, including the President's Task Force on Communications Policy4 and the Cabinet Committee on Price Stability, have recently addressed particular aspects of regulation. But what has been lacking thus far is an attempt to evaluate its basic soundness. Much criticized in the details of its application, regulation is assumed by nearly all who work or write in the field, as by the public in general, to be fundamentally inevitable, wise, and necessary. However, personal experience as a government lawyer involved in regulatory matters made me skeptical about the validity of the assumption and this study has convinced me that in fact public utility regulation is probably not a useful exertion of governmental powers; that its benefits cannot be shown to outweigh its costs; and that even in markets where efficiency dictates monopoly we might do better to allow natural economic forces to determine business conduct and performance subject only to the constraints of antitrust policy. I would stress, however, that no general challenge to government regulation of business is intended. One regulatory framework whose continued existence is explicitly presupposed by my analysis is, as just mentioned, the antitrust laws. Regulations enforcing standards of health or safety are instances of the many other government constraints on business activity that lie outside the scope of my critique.

The Article, in four parts, attempts to (1) identify areas of behavior (such as prices and profits) where an unregulated natural monopolist might pursue policies contrary to the welfare of society; (2) describe the regulatory process as it operates today arid, in a rough way, evaluate its social benefits and costs; (3) assess the possibilities of constructive reform; (4) consider some alternatives to regulation and offer some practical suggestions.

I. The Grounds for Regulating Prices, Entry, or Other Business

Conduct in a Natural Monopoly Market

In this opening branch of the analysis, I shall have nothing directly to say about the concepts or practice of regulation. Rather, I shall ask in what respects one might expect business performance under conditions of natural monopoly to be unsatisfactory from a social standpoint. When these elements of predictably deficient performance have been isolated, it will be possible to consider the extent to which the regulatory process is responsive to actual and serious problems.

A. Monopoly Prices and Profits

Under competition, the price of a good to the consumer tends to be bid down by the sellers to its cost (including in cost such profit as is required to attract capital into the industry). Consumers, as a result, obtain many goods at prices that are appreciably lower than the actual value of the goods to them. Monopoly enables the seller to capture much of the extra value that would otherwise accrue to consumers. To illustrate, let us suppose that if aspirin is sold at 1 cent per half grain (its cost) there will be 200 purchasers and that if it is sold at 10 cents there will still be 100 purchasers. The monopolist who desires to maximize his profit will sell at 10 cents—the monopoly price—where his total cost will be $1 and his revenue $10, producing a supracompetitive profit of $9. Monopoly prices are widely considered to be socially undesirable because of their alleged effects on income distribution, overall economic stability, the allocation of economic resources, and proper business incentives. The arguments in support of these grounds are briefly as follows:

The effect of charging a monopoly price is to transfer wealth from the consumers of a product to the owners of the firm selling it.5 The consumers are deprived of much of the extra value that they would enjoy in a competitive market, where they would be able to purchase at cost; the stockholders are enriched by capturing a good part of that value in increased profits. Transfers or redistributions of wealth are unavoidable in a society that is not perfectly egalitarian. At the same time, one could argue that it is sound social policy to reduce disparities of income and wealth so far as compatible with maintaining proper incentives. The redistribution of wealth that monopoly profits effect seems inconsistent with that goal. Consumers as a class are probably less affluent than stockholders; and a monopoly profit performs no obvious incentive function (our definition of cost included a profit sufficient to keep the firm in business).

It is further argued that insufficient demand in the private sector, a cause of recession, could be aggravated by a transfer of income from consumers to investors. The latter, being a more affluent group, are apt to save a larger proportion of their income. In periods of declining demand, moreover, a monopolist may be slower to reduce price than a competitive firm. In addition., by creating higher prices than would prevail under competition monopolization might be thought to aggravate any inflationary tendencies. And since a monopolist (as we shall soon see) uses less of the factors of production than a competitive firm, monopoly might appear to promote unemployment.

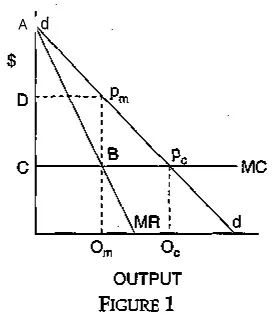

The mere act of redistributing wealth between two classes of individuals, while possibly offensive to ideals of social justice or adverse to the proper working of the business cycle, is not inconsistent with obtaining maximum benefit from the nation's economic resources. But the means by which the monopolist seeks to maximize profits may create inefficiency. Suppose that a widget costs 4 cents to produce (regardless of quantity) and that the widget monopolist can sell 10,000 at 7 cents, 12,000 at 6 cents, 13,000 at 5 cents, and 14,000 at 4 cents. Given this demand schedule, the profit-maximizing monopolist will sell at 7 cents, where his total cost is $400, his total revenue $700, and his monopoly profit $300. Whether we prefer stockholders or consumers to derive the greater benefit from the production of widgets, society as a whole is worse off when the monopoly price of 7 cents is charged rather than the competitive price of 4 cents. When 14,000 are sold at the competitive price, consumers who would have taken 10,000 widgets at 7 cents derive extra value of $300 from being able to purchase at cost. This just offsets the monopolist's loss, but there are further gains: Consumers who would have purchased an additional 2,000 at a price of 6 cents derive a value of $40 above what they paid at the competitive price; and those who would have paid 5 cents each for the additional 1,000 derive extra value aggregating $10.The total consumers' surplus when the competitive price is charged is thus $350. This sum exceeds the monopoly profit (or producer's surplus)—$300—that the seller obtained by charging a higher price.6

The intuitive basis of the illustration is quite simple. Because the utility functions of individuals vary, the monopolist selling at a single price cannot capture the entire consumers' surplus that a sale at cost would produce. The price that captures as much as possible necessarily excludes a group of potential consumers to whom the utility of the product exceeded its cost of manufacture. The monopoly price thus prevents the economic system from meeting wants that could be met perfectly well. Consumers may be led to substitute more costly or less useful products merely because the cost of widgets to them is too high, although society's economic resources would be better used producing widgets rather than substitute products. It can also be shown that in limiting output the monopolist is underutilizing productive resources.

Finally., the ability to obtain very substantial profits without particular exertion, merely as a consequence of enjoying a monopoly, may be thought to dull incentives to efficient and progressive operation. A firm that is continuously and effortlessly very profitable may not feel much sense of urgency about reducing costs in order to obtain still greater profits.

The case for condemning monopoly prices and profits just outlined is less compelling than it perhaps first appears. It is not clear that an unregulated monopolist will normally charge a price that greatly exceeds what a nonmonopolist Would charge for the same service; nor is it clear that society should be deeply concerned if a natural monopolist does charge an excessive price.

One possible ground for doubting that grossly excessive prices and profits are likely to flow from the possession of a monopoly can be derived from the theory that the large modern corporation does not seek to maximize profit.7 The revisionist theory, as one might apply it to a monopolist, may be summarized briefly as follows: Management in the large modern corporation is largely autonomous and self-perpetuating. The nominal owners, the stockholders, will assert control only if the corporation fails to produce a respectable profit, comparable to that of similar firms but not necessarily the maximum that management could extract. To be sure, if competition is sufficiently vigorous, the managers will be constrained, not by stockholders but by the market, to sell as dearly as they can while minimizing cost. Under competition, there is in theory only one profit—the return necessary to attract and hold capital—not a range of possible profits that includes a comfortable but moderate return near the bottom of that range. But it is possible that in many industries price competition is not very effective due to fewness of sellers, barriers to entry by new competitors, and other factors. Management in such industries may enjoy a broad area of discretion as to how much profit, to make. Since the managers, it is argued, derive no direct pecuniary benefit from higher profits, they can be expected to subordinate profit maximization to objectives of more immediate personal concern, such as security, corporate image, pleasant surrounding, good labor relations, high salaries, empire building, and so forth. Such tendencies should be especially pronounced among monopolists, since they enjoy the greatest freedom from competitive pressures. From this it might seem proper to infer that an unregulated monopolist would not charge monopoly prices or collect monopoly profits.

I consider this dubious reasoning. To begin with, the view that managers of a publicly held firm are likely to maximize stockholder earnings is at least as plausible as the view that they are not. Investors do care a great deal about the earnings of the firms in which they invest, since earnings significantly affect both dividends and the market value of a stock. Large investors, at least, do have ways of impressing their concerns on management. And the take-over bid is not unknown. It constitutes an ever-present threat to the incumbent management, and like any deterrent its effectiveness cannot be measured by the frequency with which it is actually employed. Moreover, most firms require access to outside capital as at least a marginal source of funds, and diminished earnings will mean diminished funds from the sale of additional securities. Even if not coerced by stockholders or market forces to maximize earnings, business managers might adopt that course because they viewed earnings as the most appropriate criterion of business success and the surest path to prestige, security, and other elements of personal fulfillment. Not least, managers typically do own stock in their company, not enough for control but quite enough to give them a substantial personal stake in the stock's performance and therefore in the firm's earnings.

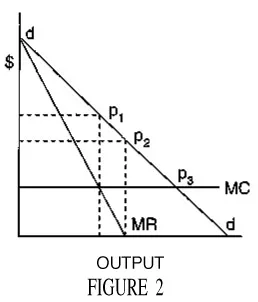

The empirical evidence on profit maximization by large and relatively secure firms is as yet inconclusive. We know, for example, that patent and copyright holders and other monopolists commonly practice price discrimination.8 As we shall soon see, discrimination is the profit-maximizing strategy of a monopolist. At the same time it is highly unpopular with purchasers, government agencies, and society at large. Its prevalence in these circumstances is some indication of the persistence of the profit drive among those insulated from direct competitive pressures. But it is an inconclusive indication. We shall soon see that price discrimination is consistent with other corporate goals besides maximizing the shareholders' earnings.

The evidence in support of the new theories of the firm is also impressionistic and inconclusive.9 Perhaps the best evidence is the fact that many corporations make charitable contributions. However, the amounts that corporations give to charity are trivial in relation to their profits10 and one of the reasons why this is so, surely, is that stockholders would be justifiably outraged to see management divert substantial profits, properly theirs, to charitable ends of the managers' devising. At most, such evidence indicates that firms do not always seek to maximize short-run profit when to do so might undermine the firm's prosperity in the long run. A charitable contribution is fully consistent with long-run profit maximization; a modest expenditure buys an asset of some value to any firm appraising its long-term prospects—public goodwill. The corporate-gift example suggests a reconciliation of the opposing viewpoints in the debate over profit maximization: the large corporation seeks to maximize profits, but over the long rather than the short run.11

A more critical point for our purposes is that even if the management of a monopolistic firm chooses not to maximize shareholder earnings—profits in the accounting sense—it might charge the same price that a conventional profit maximizer would charge, that is, the monopoly price. "Profit" and "profit maximization" are ambiguous concepts. To say that a firm is not maximizing profit may mean any one of a number of different things, and it is necessary to distinguish them. First, it may mean that the managers are, in effect, diverting monopoly profits to themselves in the form of salaries, bonuses, perquisites, and staff far in excess of what is required to attract and retain a competent management.12 Such a course of action, if pursued by the management of a monopoly firm, would require the fixing of a monopoly price in order to support the abnormal return to the managers.

Second, insistent upon only moderate profit, the management of a monopolistic firm might be slack and allow costs to drift upward.

This hypothesis also assumes that prices well above the minimum attainable cost level are being charged. Third, management might try to maximize profit but fail because of uncertainty about demand, costs, and other relevant conditions. Or, baffled by the complexities of determining the precise combination of outputs and prices that maximizes profit, management might fall back on mo...