- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Few provisions of the American Constitution have had such a tumultuous history as the contract clause. Prompted by efforts in a number of states to interfere with debtor-creditor relationships after the Revolution, the clause—Article I, Section 10—reads that no state shall “pass any. . . Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.” Honoring contractual commitments, in the framers’ view, would serve the public interest to encourage commerce and economic growth. How the contract clause has fared, as chronicled in this book by James W. Ely, Jr., tells us a great deal about the shifting concerns and assumptions of Americans. Its history provides a window on matters central to American constitutional history, including the protection of economic rights, the growth of judicial review, and the role of federalism.

Under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall, the Supreme Court construed the provision expansively, and it rapidly became the primary vehicle for federal judicial review of state legislation before the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, the contract clause was one of the most litigated provisions of the Constitution throughout the nineteenth century, and its history reflects the impact of wars, economic distress, and political currents on reading the Constitution. Ely shows how, over time, the courts carved out several malleable exceptions to the constitutional protection of contracts—most notably the notion of an inalienable police power—thus weakening the contract clause and enhancing state regulatory authority. His study documents the near-fatal blow dealt to the provision by New Deal constitutionalism, when the perceived need for governmental intervention in the economy superseded the economic rights of individuals.

Though the 1970s saw a modest revival of interest in the contract clause, the criteria for invoking it remain uncertain. And yet, as state and local governments try to trim the benefits of public sector employees, the provision has once again figured prominently in litigation. In this book, James Ely gives us a timely, analytical lens for understanding these contemporary challenges, as well as the critical historical significance of the contract clause.

Under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall, the Supreme Court construed the provision expansively, and it rapidly became the primary vehicle for federal judicial review of state legislation before the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, the contract clause was one of the most litigated provisions of the Constitution throughout the nineteenth century, and its history reflects the impact of wars, economic distress, and political currents on reading the Constitution. Ely shows how, over time, the courts carved out several malleable exceptions to the constitutional protection of contracts—most notably the notion of an inalienable police power—thus weakening the contract clause and enhancing state regulatory authority. His study documents the near-fatal blow dealt to the provision by New Deal constitutionalism, when the perceived need for governmental intervention in the economy superseded the economic rights of individuals.

Though the 1970s saw a modest revival of interest in the contract clause, the criteria for invoking it remain uncertain. And yet, as state and local governments try to trim the benefits of public sector employees, the provision has once again figured prominently in litigation. In this book, James Ely gives us a timely, analytical lens for understanding these contemporary challenges, as well as the critical historical significance of the contract clause.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Contract Clause by James W. Jr. Ely in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Public Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University Press of KansasYear

2016Print ISBN

9780700623075, 9780700623075eBook ISBN

9780700623082chapter 1

Origins and Early Development

Forrest McDonald remarked that the adoption of the contract clause at the constitutional convention “is shrouded in mystery.”1 To unravel this mystery, one must start by considering the economic changes experienced by the American colonies during the eighteenth century. As the colonies grew and became more prosperous, they gradually rejected the doctrine of mercantilism inherited from Great Britain, with its emphasis upon governmental controls, in favor of an emerging market economy. Wage and price regulations, as well as the system of exclusive public markets, gradually atrophied.2 Moreover, the law governing real property was revamped little by little to facilitate land transactions, thereby treating landed property increasingly as a market commodity.3

As price controls and regulated markets declined, and land speculation quickened, contracts assumed a more prominent role in the growing commercial society of the eighteenth century. In an expanding economy merchants were more likely to trade with or extend credit to persons who were strangers. Under such circumstances, transactions could no longer be grounded in custom or trust. Hence, private bargains in an impersonal market were increasingly determined by written agreements. Parties became accustomed to making deals and looking out for their own interests. Contracts provided a vehicle by which individuals could bargain for their own advantage.4 The product of private negotiation, not governmental authority, contractual exchanges not only encouraged economic efficiency but also underscored the autonomy of individuals. To achieve these goals, the stability of contracts was essential. It was necessary that bargains be honored and not subject to subsequent legislative interference.

A careful study of Virginia bears out the waxing of contract law and a market economy. William E. Nelson found that “a vibrant market economy” based on tobacco sales developed as early as the mid-seventeenth century. This robust economy “gave rise to complex commercial transactions and commercial litigation.” Nelson concluded that in Virginia by the 1640s “the hallmark doctrine of market capitalism, that individuals should be free to enter into contracts which courts would then enforce, was firmly in place.”5

post-revolutionary era

The troubled conditions of post-Revolutionary America, however, presented serious challenges to an economy based on private bargaining. Independence from Great Britain caused considerable economic dislocation. It ended the trade restrictions imposed by the British Navigation Acts but also brought about the loss of markets with Great Britain and its other colonies. In addition, the Revolution caused wholesale interference with private economic relationships by state legislatures. Reacting to the depressed economic climate in the wake of independence, state lawmakers enacted a variety of debt-relief laws to assist debtors at the expense of creditors. They passed laws staying the collection of debts, allowing the payment of debts in installments, and authorizing the payment of debts in commodities.6 South Carolina’s Pine Barren Act of 1785 was a particularly egregious measure. Under this act debtors could tender distant property or worthless pineland to satisfy outstanding obligations.7 State lawmakers also issued quantities of paper money and made such paper currency legal tender for the payment of debts. These measures not only hampered commerce by frustrating the enforcement of contracts but seemingly portended threats to the security of property generally. Creditors and merchants saw these laws as little more than a confiscation of their property interests.

Although popular in some quarters, legislative tampering with agreements aroused intense criticism. In 1786, for example, Noah Webster, later the author of a famous dictionary, declared, “But remember that past contracts are sacred things; that Legislatures have no right to interfere with them; they have no right to say, a debt shall be paid at a discount, or in any manner which the parties never intended. It is the business of justice to fulfil the intention of parties in contracts, not to defeat them.”8 Alexander Hamilton, while secretary of the Treasury, pictured state legislative interference with contracts as rendering commerce uncertain and as weakening the security of property.9 Likewise, Chief Justice John Marshall later recalled the deleterious impact on society of laws meddling with contracts in the newly independent United States:

The power of changing the relative situation of debtor and creditor, of interfering with contracts, a power which comes home to every man, touches the interest of all, and controls the conduct of every individual in those things which he supposes to be proper for his own exclusive management, had been used to such an excess by the State legislatures, as to break in upon the ordinary intercourse of society, and destroy all confidence between man and man. The mischief had become so great, so alarming, as not only to impair commercial intercourse, and threaten the existence of credit, but to sap the morals of the people, and destroy the sanctity of private faith. To guard against the continuance of the evil was an object of deep interest with all the truly wise, as well as the virtuous, of this great community, and was one of the important benefits expected from the reform of the government.10

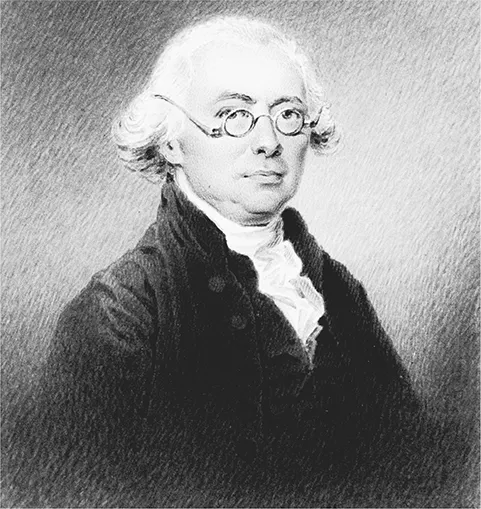

Legislative interference with contractual arrangements was not confined to debt-relief laws. Consider the controversy over the revocation of the charter of the Bank of North America. The first incorporated bank in the United States, the Bank of North America received charters from the Continental Congress in 1781 and the Pennsylvania legislature the following year. Given doubts about the authority of Congress to grant charters of incorporation, the Bank was generally regarded as a Pennsylvania institution. In 1785 the Pennsylvania legislature, responding to pressure from radicals and agrarians, moved to annul the charter. Critics maintained that the bank encouraged the accumulation of capital and hampered the issuance of paper money by the state. The repeal proposal triggered a bitter debate in the state.11 James Wilson, a prominent lawyer and later a member of the constitutional convention and a Supreme Court justice, took the lead in defending the bank. Wilson had borrowed heavily from the bank, and thus he may have been as concerned with his personal economic advantage as with the security of charters. Whatever his motives, Wilson’s arguments in support of the bank were prescient. In a widely circulated pamphlet, Considerations on the Bank of North America, Wilson attacked repeal as economic folly. More important for our purposes, he argued that the act incorporating the bank amounted to a contract between the state and the corporation that the legislature was bound to respect. Wilson insisted that “while the terms are observed on one side, the compact cannot, consistently with the rules of good faith, be departed from on the other.” Noting the practical significance of corporate charters, he added, “To receive the legislative stamp of stability and permanency, acts of incorporation are applied for from the legislature. If these acts may be repealed without notice, without accusation, without hearing, without proof, without forfeiture; where is the stamp of their stability?”12 In a nutshell, Wilson contended that a state was obligated to honor its own undertakings and that stability in regard to corporate charters was essential for successful enterprise. As Jennifer Nedelsky pointed out, “Not only did [Wilson] think that upholding contracts was extremely important economically, he saw the obligation of contract as part of the fundamental obligation to fulfill promises which makes society possible.”13 Other legislators echoed Wilson, with one insisting that “charters are a species of property.”14

James Wilson argued in 1785 that legislative grants of corporate charters amounted to contracts, and he subsequently championed adoption of the contract clause as part of the Constitution. (Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY)

These arguments did not prevail in 1785. Defenders of the repeal law denied that a corporate charter should be treated as a contract and stressed the power of the legislature to revoke charters.15 Although the charter was rescinded, Wilson had anticipated much constitutional jurisprudence. Indeed, one scholar has contended that the contract clause “was an outgrowth of the arguments about Pennsylvania’s authority to breach its own contract.”16

Wilson was not alone in advancing these views. In 1786 Pelatiah Webster, a Philadelphia merchant and author of several pamphlets on finance and government, reiterated the points stressed by Wilson. Maintaining that “charters (or rights of individuals or companies, secured by the State) have ever been considered as a kind of sacred things,” he denied that legislatures could repeal the grant and destroy the rights of the grantee. Webster even argued that “the sacred force of contracts binds stronger in an act of state, than in the act of an individual, because the whole government is injured and weakened by a violation of the public faith.”17

As these comments indicate, state interference with the rights of creditors, when coupled with the revocation of an important corporate charter, bitterly disappointed many political leaders of the Post-Revolutionary Era. They became convinced that state protection of economic rights was inadequate. Historians generally agree that the establishment of safeguards for private property was one of the principal objectives of the constitutional convention of 1787. “Perhaps the most important value of the Founding Fathers of the American constitutional period,” Stuart Bruchey has cogently pointed out, “was their belief in the necessity of securing property rights.”18 Delegates repeatedly stressed this theme during the convention. For instance, James Madison asserted at the Philadelphia convention that “the primary objects of civil society are the security of property and public safety.”19

The first provision protective of contractual rights was part of the Northwest Ordinance of July 1787. Passed by the Confederation Congress while the constitutional convention was meeting in Philadelphia, the Northwest Ordinance established a framework for territorial governance in the Old Northwest. Articulating a number of fundamental principles, the Northwest Ordinance had much of the character of a constitutional document.20 The Northwest Ordinance contained several important provisions regarding the rights of property owners, including one ensuring the sanctity of private contracts. Article 2 of the Northwest Ordinance stated, “And, in the just preservation of rights and property, it is understood and declared, that no law ought ever to be made or have force in the said territory, that shall, in any manner whatever, interfere with or affect private contracts, or engagements, bona fide, and without fraud previously formed.”21 This language may have been inserted in response to Shays’s Rebellion in Massachusetts, which sought to prevent the collection of debts. It has also been seen as part of a larger scheme to encourage commercial development in the largely unsettled territories. Viewed in this light, the protection of agreements was a crucial step in attracting eastern investors. The territorial government was prevented from abridging private economic deals, creating a hospitable climate for outside capital.22 The contract clause in the Northwest Ordinance foreshadowed the step to forge a constitutional guarantee of existing contracts.

the constitutional convention

Given the concern shared by many delegates to the constitutional convention that state governments were invading property and contractual rights and hampering commerce, it is hardly a surprise that the new Constitution contained a cluster of provisions designed to rectify the abuses at the state level. Thus, the Constitution prevented the states from enacting bills of attainder and from making anything but gold or silver legal tender for the payment of debts.

A provision barring the state...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Origins and Early Development

- Chapter 2: The Era of John Marshall, 1801–1835

- Chapter 3: The Taney Era

- Chapter 4: The Eras of the Civil War and Reconstruction

- Chapter 5: The Gilded Age

- Chapter 6: The Early Twentieth Century

- Chapter 7: The Contract Clause in the Age of Regulation

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Cases

- Index

- Back Cover