1 | The Troubled Frontier

Background

Few places in the 1920s captured the public imagination like Manchuria. For outsiders, it appeared to be the ideal land for dreamers, adventurers, and romantics. As Junichi Saga, a Japanese soldier who served on the Korean–Manchurian border in the 1920s, recounted, “There was a feeling in Japan in those days that anything was possible if you went to Manchuria.”1 Businessmen from America and British bankers eagerly sought out their chance to make their mark in the booming economy. The land, especially the northern regions, also held the allure of the American Wild West of the nineteenth century, where trappers could make a small fortune selling furs, outlaws and bandit gangs hid in remote hideouts, prospectors panned for alluvial gold along remote streams and rivers, and bears and Siberian tigers still ruled parts of the forested wilderness. For the large majority of people, however, a more routine yet rewarding life was spent in the cities, villages, and farms. The region remained, as South Manchuria Railway (SMR) officials described it, a “land of opportunities.”2

Some 940,000 square kilometers in size, larger than France and Germany combined, it was the home to nearly one tenth of China’s population, over 30 million people, including 1 million seasonal workers, known as sparrows, who annually migrated from China’s northern provinces, especially Shantung. While it boasted of one of Asia’s largest multiethnic communities—there were some 2,900,000 Manchus, 350,000 Mongols, half a million ethnic Koreans, 200,000 Japanese, and 141,000 Russians—it was also a magnet for refugees and misfits, as nearly one fourth of the Russian population had arrived in the Northeast during the 1917–1922 Russian civil war, while the number of bandits was put at an astounding 58,000 in 1929.3

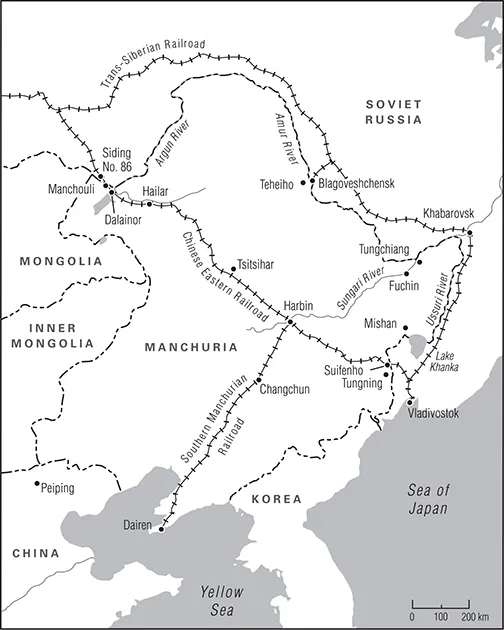

The Northeast in 1929 could be seen to begin at the southernmost tip of the Liaotung Peninsula on the small Kwantung Peninsula containing the port city of Dairen and then extending up the Liao River north toward Mukden, the first capital of the Manchu Empire (See Map 1 for an overview of the Northeast.) This was the region’s economic heart; only the Shanghai metropolis surpassed its concentration of industries and manufacturing plants. Moving northward, the land stretched out into the Central or Tsitsihar Plain, the richest and fastest-growing agricultural region in China. The Greater Khingan Mountains bounded the western edge of the plain; continuing west through mountains, the Northeast then opened onto the plateau of flat marshes and grasslands of northernmost Inner Mongolia until it reached the Argun River and the Soviet border. To the east of the Tsitsihar Plain lay the Yalu River, the Tunghua Mountains, and Tumen River, which together (from south to north) formed the boundary with Japanese-controlled Korea. Continuing north, the plain abutted Lake Khanka with the Ussuri River and the eastern border with Soviet Russia. From the Tsitsihar plain to the north lay the great Amur River basin, the most coveted piece of terrain in Asia—a region that China, Russia, and Japan all wished to dominate.

Troubles along the Amur River began as soon as Cossack expeditions loyal to Tsar Alexis I first reached its banks in the mid-1600s and the river became a flash point between the native Manchus and Russians until the 1689 Nerchinsk treaty delineated a border between the two empires. The treaty served to keep the peace for the next 170 years and helped to define what came to known as Manchuria in the 1920s. The notable exception was Manchu control over the Amur River watershed, which ended with the 1858 Aigun treaty, when the Russians were able to force a prostate Ch’ing China—having been defeated by the British and French in the Second Opium or Arrow War—to cede to Russia all lands east of the Ussuri and north of the Amur River. The Amur was also known as the Heilungkiang, or Black Dragon River. The river basin remained politically charged. Not only was the area contested over by the Chinese and Russian empires, but the Black Dragon Society became the name adopted by Japan’s first ultraimperialist association in 1901—a group that urged expansion onto the Northeastern Asian mainland. The arrival of Japan completed the triad of powers that would fight politically, militarily, and economically to control Manchuria during the opening decades of the twentieth century.4

These competing interests, combined with Warlord Era (1916–1928) chaos, shaped the governance in the Northeast, and by 1929, it was a complex tapestry of overlapping authorities. The entire Northeast was under the rule of Chang Hsueh-liang, also known as the Young Marshal. Below him were governors-general who ruled the three provinces of Fengtien, Kirin, and Heilungkiang along with the Harbin special administrative area, which included the Chinese Eastern Railroad (CER) Zone under joint Chinese and Soviet Russian management and administered by a general appointed by the Kirin governor (although the Heilungkiang governor had responsibility for the zone in that province). Finally, the Kwantung Leasehold and SMR Zone fell under Japanese jurisdiction.

Of the three Northeastern provinces, Fengtien was the richest and most populous. Much of it had long been part of the Chinese Empire, and the first to have a foreign concession carved out of it: the Russian naval base at Port Arthur and the commercial port of Dairen. The surrounding lands, encompassing some 3,500 square kilometers, was a possession that passed into Japanese hands after the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. Kirin, located northeast of Fengtien, was larger in size but had a smaller population and was less developed. It was the home of Harbin, the multiethnic city and site of the CER headquarters. Heilungkiang, stretching from the Sungari River in the east to the Argun River, 1,200 kilometers to the west, was the largest, most diverse, and least populated of the provinces. It also shared the longest border with Soviet Russia. The population was predominantly Chinese except in the far western border region that followed the Argun, which was home to Bargut–Mongol herdsmen and ethnic Russian farmers of the Starovery (Old Orthodox Believers) who had arrived in the 1880s. During the Russian civil war (1917–1922), other Old Orthodox Believer families fled the fighting in the Russian far east and joined the original settlers.5

Economically, Manchuria was China’s richest and fastest-growing region, an agriculture dynamo with 30 million acres under cultivation and another 30 million awaiting development. John B. Powell, an American newspaper reporter who covered the 1929 war, reflected on the lands around Tsitsihar, the capital of Heilungkiang province located in the northern end of the plain: “I was constantly reminded of the fertile farm lands and the deep black soil of northern Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa.”6 The range of agricultural goods produced was breathtaking: fruit trees and sugar beets, the traditional staple of kaoliang (sorghum), and grains such as barley, corn, millet, rice, and wheat abounded. The greatest source of agricultural wealth, which had only been cultivated on a large scale for a few decades, was the protein-rich soybean, a crop that Manchuria exported across the globe in the form of dried beans, oil, and cakes (hardened bean paste formed into densely packed cylinders measuring roughly two feet in diameter and five inches in thickness). Hemp, tussah, tobacco, and cotton were also produced. Most farmers also possessed a few head of livestock and fowls; the estimated number of domestic animals, flocks, and herds was put at over 20 million, with over 4 million pounds of wool exported annually.7

The abundance of land allowed farmers to follow a different path from the rest of China, as it mitigated the ill effects of rural landlordism and helped account for the fact that Manchurian farmers were generally better-off than their counterparts elsewhere. The most richly cultivated region began in the south where the Liao River entered the Bay of Pohai, an area that had been integrated into China for centuries with an agricultural system based on the long-established market town model. To the north, a region populated by newer immigrant farmers, the model changed to larger stand-alone family farms; ethnicity also played a role, as farmers of Korean descent dominated rice production. Geography and climate were the final determinants of Manchuria’s unique agricultural profile. The alluvial lands of the Tsitsihar Plain held vast fields of soybeans and kaoliang, while corn grew better farther south toward the Liaotung Peninsula and wheat grew best in the northern reaches of the plain. Finally, the valley formed by the upper Sungari River offered soils ideal for cultivating wheat, millet, and soybeans. A variety of mofang or local mills, usually employing fewer than ten people, distilled the kaoliang or milled the soybeans into oil or cakes and the grains into flour, although large-scale mills, known as huomo or fire mills, using steam or electrically powered machinery, often government owned, were becoming commonplace by 1929. One advantage for the farmers was that none of the main agricultural regions was located along the border with Soviet Russia, sparing the large majority of the population from any direct involvement in the war.8

Timber was another source of natural wealth, with over five hundred billion cubic feet of timber available that could be easily shipped by rivers and streams, but the numbers were deceiving, as the sustainable supplies were in the north in Heilungkiang while parts of Fengtien province in the south were undergoing a process of afforestation resulting from earlier overharvesting. Mining centered on the two essentials of a modern 1920s economy, coal and iron ore, and Manchuria possessed ample reserves of both, with control over the resources dominated by the CER and SMR. The most productive mine at Anshan, located forty kilometers southwest of Mukden, held a projected 200 million tons of iron ore, while the Fushun open-pit coal mines, stretching fifteen kilometers in length and located forty kilometers to the southeast of Mukden, contained over one billion tons of bituminous coal that supplied not only large quantities of coal and coke but also oil (all under consignment to the Imperial Japanese Navy), natural gas, gasoline, tar, and sulfuric acid. By 1929, the output from the Fushun mines accounted for one third of all the coal produced in China. Together, they made the Mukden region the largest steel-producing center in China, and both had been developed by and were under the control the SMR. The CER controlled the Muleng coal mines near Mishan in northern Heilungkiang, at Dalainor in the far west, and at Koshan, northeast of Tsitsihar in central Manchuria.9

Japanese steel mills, both in Japan and the Northeast, fed by ore from Anshan and coal from Fushun, combined with the specialized Ta-Hua Electro-Metallurgical Company, helped explain in part why Japan was both the largest steel producer in East Asia and so insistent on its special position in Manchuria. While the manufacturing facilities in the Kwantung Leasehold and the SMR Zone did make Japan the industrial power in Manchuria, there were extensive Chinese holdings as well. Situated near Mukden...