![]()

PART I

Prelude

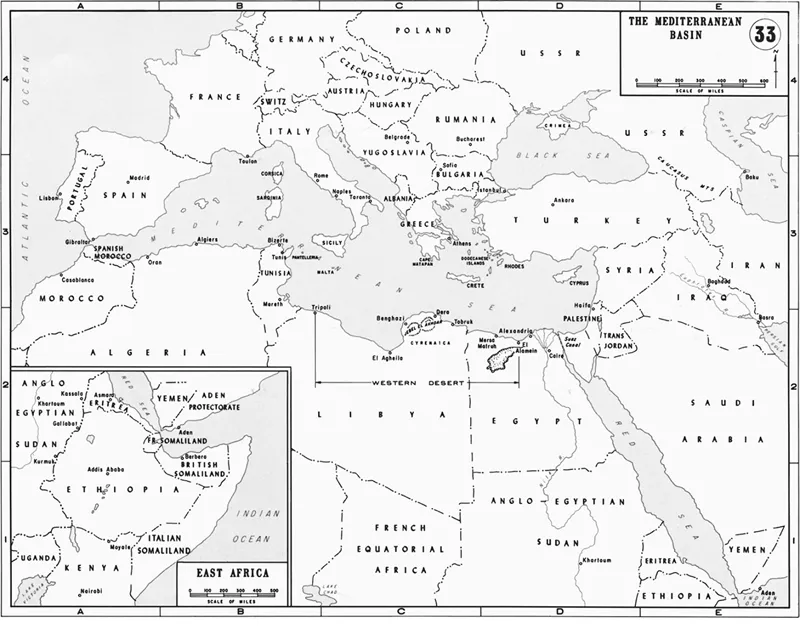

The Mediterranean and Middle East theater (this was the British title; the Americans referred to it as the Mediterranean Theater of War) covered an area of more than 3 million square miles. Its geography demanded a capable and complex interplay between land, sea, and air forces. The side that learned more effectively to employ combined-arms operations within the theater, based on sound grand and military strategies, would have a major advantage. (Maps Department of the US Military Academy, West Point)

![]()

1

The Approach to War

Events to June 1940

The Grand-Strategic Context

Any examination of the role of airpower in the Mediterranean theater of war must begin with a wider look at the theater’s grand-strategic importance. Because of the Mediterranean’s geographical makeup, combat in any of its many subregions was bound to feature a major air presence given this relatively new weapon’s ability to strike deeply from land bases. Land-based airpower in many ways set the tone and direction of the conflict in the Mediterranean, although always in conjunction with, and correspondingly dependent upon, land and naval forces. How each of the warring powers chose to employ air assets was tied in large measure to its grand-strategic views of the Mediterranean.

Unfortunately, most existing studies mischaracterize the Mediterranean as anything from a subsidiary (if important) theater to an irrelevant one. This “irrelevance” was, as a number of historians have asserted, the result of a misconceived Allied approach to the theater. As one scholar noted, “The consequence of this Allied stumble into a poorly thought-out and ‘opportunistic’ Mediterranean strategy was a dreadful slogging match in which the British and subsequently the Americans were outgeneraled and outfought around the shores of a sea of trifling importance.”1 Another was nearly as categorical when he argued that the Mediterranean was a “cul-de-sac . . . a mere byplay in the conclusion of a war won in mass battles on the Eastern and Western Fronts.”2 One particularly negative assessment holds that “the reality was that Great Britain sacrificed vital interests, such as the home front and Singapore, and paid an exorbitant cost in shipping to maintain for three years a small army in a peripheral campaign far from the German jugular. Britain fought in the Mediterranean because from 1940 to 1943 there was no other place where it could fight without the prospect of total defeat.”3 Finally, another asserts that “Britain was ambivalent about the Mediterranean. While it was neither vital to its own survival nor to that of the British Empire, Britain was incapable of releasing it. It repeatedly devoted to it significant resources which could have more effectively been used elsewhere.”4 Other scholars opined that “from the strategic point of view the Middle East offered [Hitler] few possibilities.”5

Others have hedged their bets. One said of the Mediterranean theater, “Whether the expenditure in resources was worth the results remains a matter of controversy.”6 He concluded that “although a secondary theater of war . . . the Mediterranean campaigns nevertheless are a vital part of the history of the Second World War.”7 Given the importance of the Middle Sea to the British as a conduit to their Far East holdings and the means of protecting their access to oil supplies, these assertions ring hollow, especially when one considers the major strategic benefits conferred by victory in the Mediterranean, including the destruction of an entire Axis field army, air supremacy over southern Europe, Italy’s surrender, and heavy-bomber missions from the Foggia airfields against key economic and transportation targets in occupied Europe, among others. The war may have been won elsewhere, but the Allies could have lost it here. One of the reasons they did not, aside from poor Axis grand strategy and relatively ineffective employment of airpower, was the Allies’ more effective use of airpower, within a combined-arms context, driven by a clear grand strategy.

Douglas Porch places the Mediterranean theater within the larger context of a global conflict for the survival of the democratic powers and then portrays it as a combined-arms effort in which the Allies ultimately prevailed. Further, he argues that “while the Mediterranean was not the decisive theater of the war, it was the pivotal theater, a requirement for Allied success,” one in which the Allies were able to “acquire fighting skills, audition leaders and staffs, and evolve the technical, operational, tactical, and intelligence systems required to invade Normandy successfully in June 1944.”8 A Commonwealth loss in the Mediterranean in 1941 or 1942 would have been disastrous for the Allied war effort. The Axis would have seized enormous oil resources, passage for U-boats through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean, a back door into the Soviet Union and Turkey, and a possible linkup with the Japanese that would have destroyed the British position in India.9

We must view all of this within the context of the Mediterranean’s geography, which was a “strategist’s nightmare,” particularly with the advent of land-based airpower.10 Because of the geography of the Mediterranean and adjoining regions such as the Middle East and Italian East Africa (IEA), it was a sea-air-land theater more so than any other in the war. The British understood this, mostly because of their imperial interests, and they planned to fight for control of the region. However, after the Luftwaffe savaged the Royal Navy during the evacuation of Crete, the escort of convoys to Malta, and in other engagements, it became clear that it would be impossible for the navy to operate without land-based air cover. Air forces may not have been a substitute for navies, but naval power was no substitute for airpower. Even the ground campaigns in the Western Desert were focused to a tremendous extent on capturing key airfields that could in turn serve as bases for aircraft supporting further ground advances while interdicting merchant shipping, which provided a lifeline to the warring armies. This complex interplay between air, naval, and ground operations proved crucial, and one could not succeed without the others. Malta, Gibraltar, and the Suez Canal were all crucial parts of this interplay because by holding them, the British maintained a range of important advantages.

British Priorities

It was good fortune that the British understood the Mediterranean and Middle East theater’s grand-strategic importance as well as the complexities of asserting and maintaining control over this huge area, which included the Mediterranean. In fact, they were the only ones to view the Mediterranean Basin and its surrounding areas as a “single geo-strategic unit.”11 Churchill insisted that the British would fight to the “last inch and ounce for Egypt.”12 The desert flank was “the peg on which all else hung.”13 He understood that the Mediterranean campaign could not win the war but might well lose it and used this theater as leverage with Franklin Roosevelt for US support. Churchill believed that losing the Suez Canal would be a calamity “second only to a successful invasion and final conquest” of the United Kingdom.14 The strategy had to be to conquer North Africa first, reopen the Mediterranean, and then attack Italy and knock it out of the war.15 These moves were never intended to be substitutes for an invasion of the Continent but rather indispensable preliminaries to shore up Britain’s strategic position and weaken the Axis while awaiting US entry into the war. Despite British tendencies to look for new opportunities in the Mediterranean after summer 1943, and the major disagreements these views created with the Americans, they remained focused on the defeat of the Reich by land, air, and sea, to include the invasion of northwestern Europe.

For a brief period after the Italian conquest of Abyssinia, British leaders feared that Italian land-based airpower there and in Libya would make the empire’s position in the Mediterranean untenable. Two things changed this view. First, a group of naval officers known as the “Mediterraneanists” argued that the Middle East was a must-hold theater from a grand-strategic perspective and a launching pad for any attack on Italy, should Mussolini side with Hitler. Second, the discovery of major oil reserves in Saudi Arabia in 1938 drove home with even greater force the importance of holding open and developing the sources of this crucial commodity in Iraq, Iran, and now that kingdom. Closure of the Mediterranean to shipping, combined with any serious merchant vessel (MV) shortage, would force the British to rely heavily on US oil. Consequently, they felt compelled to keep British-controlled oil in their hands. Sending oil 14,000 miles around the Cape of Good Hope to the United Kingdom was unpalatable enough; losing the oil sources altogether was unthinkable.16

The Italian conquest of Abyssinia caused the British to take actions that paid major dividends after the war began. It refocused their attention on the vital importance of the Suez Canal as the “hinge” in the empire’s commerce. The growth of air routes to India, Singapore, and Australia also depended on a secure Middle East, and this development had the added benefit of creating a far-flung network of air bases that proved its worth in the coming contest.17

Based on the growing Axis threat, the commanders in chief (C in Cs) of the Middle East theater received modest reinforcements and had time to think about key issues they would face during the war, including basing requirements, logistics, operational planning, and interservice cooperation. They prepared for a campaign they knew they could not lose. Given the theater’s huge size and the need to keep aircraft serviceability rates high, air units had to be highly mobile. This required a basing infrastructure, supplies, salvage and repair facilities, weather forecasting capability, and radar. These requirements constituted a huge logistical challenge that the British met by developing, in effect, a parallel Metropolitan Air Force in Egypt.18 As Humphrey Wynn noted, “uniquely among the [Royal Air Force (RAF)] commands, the Middle East had created a complete Air Force.”19 The distance between London and Cairo was too great to allow for any other solution. The ensuing focus on logistics, intelligence, and command and control (C2) paid enormous dividends. This, Wynn continued, “resulted largely from two factors: the supply of British and American aircraft shipped to African ports; and the support given to the Desert Air Force by the supply, maintenance and repair organization, which was radically overhauled and reorganized during 1941.”20 The RAF’s “whole air force” concept conferred important advantages in a theater of operations where complex geographical and logistical realities made land-based airpower vitally important.21

Italian Policy Aims

The Italians, too, saw airpower, along with their naval and ground forces, as a key means for achieving their objectives. However, Mussolini sought to achieve them at little cost because he knew Italy could not wage a long war. He believed the Mediterranean was rightfully Italian but also a prison within which the British and French hemmed in Italy. His focus during the 1930s, crowned by the conquest of Abyssinia, was to break out of this “prison” to secure the key geographical points that would ensure commercial outlets and military access beyond the Middle Sea and allow Italy to obtain new colonies. At a minimum, this “New Rome” would include French and Spanish Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Gibraltar, the Suez Canal, the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, and the Balkans. Only by seizing these areas, the duce reasoned, could Italy become truly self-sufficient economically and able to fend off the threats posed by Britain, France, and, more remotely, the United States. How Mussolini intended to acquire this impressive list of prizes will never be entirely clear, but he sought to employ a combination of diplomacy, perfidy, well-timed alliances, and opportunism. Mussolini planned to wage...