![]()

EMPIRES OF THE SUN BIG HISTORY AND THE GREAT PLAINS

1

In the 1980s and 1990s I lived on the Great Plains. I have never gotten over it. I grew up in southern forests and bayous, spent twenty years of my life in the Rocky Mountains of Montana, and presently live off the end of the Southern Rockies in New Mexico because I am passionately in love with deserts. And I travel to oceans, since like most of us I find something hypnotic and satisfying to my genetic memory in an ocean beach. But here’s the thing: the sea, the woods, the mountains, all suffer in comparison with the prairie. What Romantic Age celebration of landscape aesthetics used to call “the sublime”—an awe capable of stilling the dialogue in the mind—is reachable more easily in vast, horizontal plains than in any other kind of landscape. That sublimity arises from the plains’ unfathomable boundaries, a self-confident grandness of scale layered atop a kind of still, calm, monotony of sensory effect, and from the country’s entire lack of echo and strange ability to deceive. In the years I lived there, I found that, deliberately taken in with all the senses, the Great Plains endlessly stunned me. The place is a sensuous feast of the minimal.

But I do understand that there is something bigger going on here. For the last 40,000 years, since we humans left Africa and began to explore the larger world, encountering and taking the measure of one landscape after another, we have been engaged in a search. Maybe it was the same search, as some believe, that compels us in this century to Mars and beyond. But the impulse may have been simpler, for once we began to write, in the literature of exploration the places that aroused our strongest passions were places that most resembled our original African home: yellow savannahs speckled to the limits of our sight with herds and packs of wild animals. Think of the Masai Mara and the Serengeti as our templates, and the diverse bestiary of Chauvet Cave, the site of some of our earliest artistic expressions, as a subsequent remembering of whence we’d come.

The American Great Plains may be one more reminder that we can find home again. Excepting East Africa itself, 200 years ago no part of the globe quite thrilled us in the same primeval way. Today the plains out east of the mountain divide is a drought- and dust-plagued habitat of big farm machinery, ignored and ridiculed, flyover country. But before it was de-buffaloed, de-wolved, and de-grassed, the nineteenth-century Great Plains was one of the marvels of the world. With its staggering ecology of charismatic animals, the plains enabled Americans and Europeans of all backgrounds to experience home base one last time.

It was here, on these sublime horizontal yellow sweeps, which extended eastward for 500 miles beneath the rain shadow of the Rockies, that we also have the strongest argument for the oldest continuous (or almost so) story of human life in North America. This debate actually revolves around several candidate places, in locations as diverse as Alaska, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Texas, and it is a debate that may not be resolved in our lifetimes. But one overcast March day in 2005, an old friend from Montana, writer Steven Rinella, and I spent an afternoon tramping across one spot that, without any question, stands in the direct line of the founding of human history in America. The bleak, surprising setting of our immersion in Big History in America entirely lacked any of the schoolbook associations of a Jamestown or a Plymouth or a Santa Fe. But in the founding of America, it did have one great advantage not enjoyed by those more famous sites. Its story pushes definite human inhabitation of our continent back more than 13,200 years (Jamestown, 1607, and Santa Fe, 1610, seem yesterday by comparison). Thirteen-thousand years is also how long, for a certainty, we humans—the most charismatic Great Plains megafauna of all—have intertwined our lives and fortunes with the animal life of the North American plains. Once more, across a span of time that didn’t finally end until a century ago, we lived off animals.

There are arguments, to be sure, for a continental culture even older than Clovis. Centered on a small scattering of sites elsewhere in America, one of them, the Friedkin Site in the Texas Hill Country on the southeastern edge of the Great Plains, may date to 15,500 years ago. But so far no older culture we’ve found seems to have draped itself over the continent with the geographic sweep of the Clovis Paleolithic hunters, whose excavated campsites range from Montana to West Texas and the Southwest. We barely know them as a people. One recent theory is that they were a “Northern Hemisphere wild-type.” Think Siberian Vikings, a settler society of hyper-aggressive colonists whose descendants, once the giant bestiary of the Pleistocene collapsed, lost many of those traits. Analysis in 2014 of the DNA of a Clovis child from a Montana site indicated that the Clovis people were not only originally Siberians, they are the direct ancestors of 80 percent of the native population of the Americas.

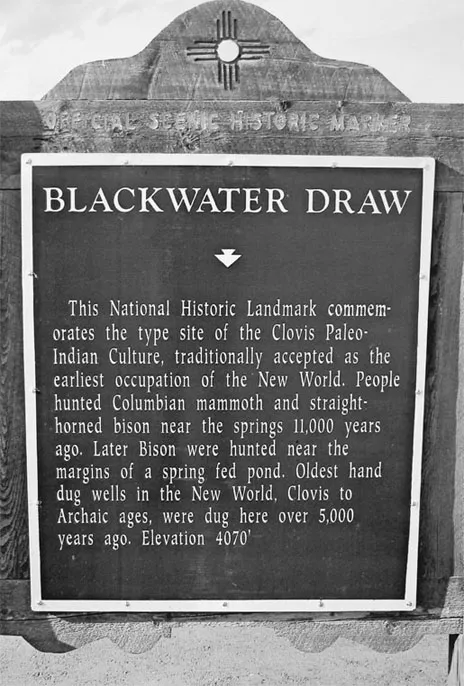

In search of Clovis America, Steven and I were out in my old home country, the Southern High Plains, although who knows what the ancient inhabitants might have called these flat prairies, seemingly endless as the ocean seas. In 1932, when archaeologists first discovered this ancient setting, near spring-fed wetlands in a shallow Pleistocene stream channel coursing these plains, the place was about to be mined for gravel to build roads through the nearby town of Clovis, New Mexico. Early settlers had named the winding, grassy channel Blackwater Draw. But as archaeologist E. B. Howard made discoveries here that rocked the world, the scientists decided to name the people whose lives they were resurrecting the “Clovis People,” after the nearby town. Eventually science would discover a “Clovisia the Beautiful” that had lasted some 400 years, almost twice as long as the modern United States has so far, and conclude that its residents had fanned out across most of America. But Blackwater Draw was where Clovis people reemerged out of the mists of the continent’s forgotten past. This marshy little valley out in the middle of plains extending thirty miles to the horizons is where one of the templates for how to live in a grand grasslands took shape.

As Steven and I followed our self-guided tour around this famous site, it became clear that the Clovis people had arrived in America at a propitious time. Large cosmic forces have shaped Earth’s Big History. There have been extra-terrestrial impacts that have reset the evolutionary clock more than once, wobbles in the Earth’s spin around its axis that have effected clocklike climate shifts cycling between Ice Ages and the Pluvials between them, plate tectonics and continental drift to raise mountain ranges and spark volcanic fireworks. And of course amidst it all has been biological evolution, refitting life for all the endless changes. But the Clovis people were lucky enough to be here when giants still roamed the continent. Indeed, it was the never-hunted Pleistocene megafauna of the Americas that had drawn the Clovis people out of Siberia in the first place.

Blackwater Draw, eastern New Mexico, site of the original discovery of the Clovis big game hunting culture of North America. Dan Flores photo.

Between 14,000 and 8,000 years ago, though, as the Wisconsin Ice Age began to wane and North America began to warm, many of the large, Africa-analogue creatures that inhabited the Americas were going extinct. But 13,000 years ago in what would one day be New Mexico, it was still possible for the Clovis people to specialize in elephants. It was the discovery of their large spear points embedded in the remains of mammoths, giant ground sloths, camels, and horses that had rocked the world in the 1930s. It confirmed something no one had believed previously, that ancient Americans had hunted giant creatures no longer found on Earth.

Walking along Blackwater Draw and gazing across these vast plains that March afternoon, the obvious observation to make was that the elephant hunt did not last. Indeed, in the early 1970s archaeologists uncovered more than 8,000 artifacts here from another culture, known as Folsom (also named after a New Mexico plains town, farther north), which succeeded the Clovis people in time. As indicated by the Folsom site, and many others like it across the West, the extinction of the elephants led the next inhabitants of this region to specialize in another of the great Pleistocene species, a massive, early bison known as Bison antiquus. But like the mammoths, in time Bison antiquus were also fated to become extinct across the Great Plains. While Folsom culture and its spinoffs perfected bison drives, corrals, and atlatl technology to enable them to survive some 2,000 years, around roughly 11,000 years ago this lifeway, too, was collapsing.

Looking around us at these immense, windy, usually brightly lit savannahs, now bereft of both elephants and giant bison (and on this particular day, even sunshine), it did not require much intellectual effort for Steven and me to discern some patterns in the deep time history of this place. Track any part of the world across the large expanses of time since humans arrived and a story begins to unfold that demonstrates a set of principles about history. First, because the grand forces mean that the Earth is an evolving and endlessly changing world, no place remains the same across Big History. The science of ecology once waxed eloquent about “climax,” the biophysical reality of environments if left undisturbed. But every environment is endlessly undergoing disturbance, or recovery from it, so that what appear to be climaxes are merely snapshots in time.

Second, human beings—like every other living species—change the places where we live. The famous geographer Yi-Fu Tuan once composed a simple and elegant aphorism: space plus culture equals place. In truth, though, only the first human inhabitants to occupy a piece of ground on Earth ever got to interact with “space.” Since we succeed one another in place after place, we end up interacting not with raw nature but with settings that have already been altered by the preceding inhabitants. Just as the Folsom people did in the wake of 400 years of Clovis life on the Great Plains, all of us who come later are engaging with someone else’s previously-created “place.” The Folsom people inherited a Great Plains without elephants, then bequeathed a plains country lacking giant bison.

A story that spans time-frames like these is the province of Big History—what French scholars have for many decades called la longue durée. In a part of the world now divided up into cities and towns and their spheres, by county and state lines—so that we tend to think of ourselves as being in “West Texas” or “the Oklahoma Panhandle” or “the Dakotas”—the plains has actually long functioned, and still does, as a distinctive ecological region that has produced a particular kind of history different from elsewhere, different because of the landscape itself. And its possibilities.

There is in fact a theory about human settlement that goes directly to the issue of possibilities for settler societies. Possibilism, as it’s known, posits that regional environments like the Southern High Plains or the Dakota or Montana Badlands do not completely determine how people will live in them. Rather they offer a range of possibilities from which we choose based on the kind of culture we bring with us. Human cultural preparation can be so different that what one group sees as a valuable potential resource, another group may entirely ignore as worthless. A region like the Southern High Plains, say, does not offer unlimited possibilities. Whaling or an economy based on processing timber would not fall within the range of lifeways any human culture might follow here. Yet out on the expansive, sunlit grasslands of the Great Plains, whose offerings might strike many from forested, wetter regions as quite limited, 13,000 years of Big History shows a fair range of possible ways of living. Always, though, following a particular dictum of nature: like the Earth itself, life on the plains revolves around the sun.

The geology, topography, climate, and biology of the Great Plains have been fundamental keys to life of all sorts in a grassland setting. What appears an unrelenting, unremarkable flatness to the topography of the plains comes from its surface geology, which is sedimentary outwash from the Rocky Mountains. Over millions of years that outwash buried ancient, carboniferous life forms from the Permian, Triassic, and in a few spots the Jurassic periods, when the country that would become the Great Plains was then ruled by dinosaurs. The overlying erosional wash from the mountains also buried very old mountain stream runoff in the form of a gigantic fossil lake we now call the Ogallala Aquifer, which lies beneath the surface from Texas to Nebraska.

Because its surface has been washed down from high mountains to the west, plains topography gradually loses elevation from west to east. Despite appearances from a car window on interstate highways, though, the Great Plains is far from tennis court–flat. Rivers out of the Rockies—the Missouri, Yellowstone, Platte, Arkansas, Cimarron, Canadian, Pecos, and hundreds of their tributaries—had carved arroyo channels, canyons, and left vast stretches of eroded badlands on the plains eons before the Clovis people ever arrived. The Red River, Brazos, and Colorado of Texas, draining off an isolated plateau called the Llano Estacado on the Southern Plains—laid down another set of long, shallow channels before sluicing away a wild, tangled, vertical landscape on the plateau’s eastern escarpment. For the last million years these smaller plateau rivers have spilled off that escarpment through deep, brightly colored canyons that expose the underlying Permian and Triassic rocks. The original Clovis site in New Mexico that Steven and I walked in 2005 is in one of the headwater channels of this system.

Geology and topography have remained fairly constant since humans got to the plains, but climate and biology have changed enormously, and often. Because the Great Plains is far inland from oceans, and the Rocky Mountains intercept much of the moisture flowing across the West from the Pacific, since humans have been here the plains has had a semi-arid climate. For the past 13,000 years it has been drier than the country on either side of it, typically bathed in 320 annual days of sunshine, and because of its slight topography and solar heating, usually very windswept. But like everywhere else on Earth, it has had a climate dramatically variable through time. The Wisconsin Glacial period produced much cooler, more lush conditions, with much more extensive tree growth across the plains then. One of the reasons we know this is because of relict populations of trees now associated with the mountains, like Rocky Mountain junipers, that still grow in wet, north-facing locations hundreds of miles out on the prairies. But there have also been hot, dry episodes that sometimes lasted not just decades but hundreds of years, and in the case of a drought called the Altithermal, for thousands.

In a landscape that powers human societies with sunlight converted by grassland photosynthesis into energy, the most direct strategy for exploiting that energy is through hunting grazing animals. Dan Flores photo.

Conditions like these have meant that the plains has been dominated by grasses, which by their nature require less water than woody vegetation. The closer to the mountains, where the rainshadow effect is pronounced, the shorter the grasses, which gradually increase to mid-height and then tall grasses on the eastern edge of the plains. A world dominated by grass and sky has meant everything in plains history. The equation is a very simple one. Biological life is dependent on energy, and since the energy that drives most terrestrial systems comes directly from the sun, grasslands in open terrain under cloudless skies tend to produce a very direct conversion of solar energy. In one simple step of photosynthesis, thermodynamic energy streaming from the sun is directly available to animals that eat grass. Hence when humans, omnivores rather than herbivores, looked to the resource possibilities on the Southern High Plains, what they readily saw were lifeways centered around converting the massive solar energy charge of the region into forms humans could use.

One final element influenced the world of possibilities on the plains: geographical context. Humans are not just social among our own groups, we seek out contacts with other human groups. And if those groups reside in environments different from ours, we trade what we produce and value for things we lack but value. Today our global market economy is the result. So it is not surprising that at signal moments in the human history of the Great Plains, its residents reached out to peoples who were following very different lifeways in very different biological regions to the west and east. The peoples of the plains, in other words, joined in regional economic systems that tied them by trade to peoples living elsewhere.

This is the framework for human history on the Great Plains from the time of the Paleolithic big game hunt, from the age of Clovis elephant hunters and Folsom bison hunters. The Folsom hunters inherited a Clovis place—“Clovisia the Beautiful”—that no longer offered the possibility of elephant hunting. In the time they dominated the plains, Folsom hunters and their several offshoots concentrated their economies on the remnant herds of Pleistocene bison, increasingly on a late subspecies, Bison antiquus occidentalis. But by 11,000 years ago the huge Pleistocene bison were gone.

Then over the next 3,000 years, one species of charismatic Pleistocene megafauna after another went extinct. Winking out in isolated little groups, the camels followed the bison, as did the giant ground sloths. Camelops, the last plains camel, sprang from a family of animals that, like horses and pronghorns, had evolved in the American West. Now this American native was extinct. Hanging on the longest, but whose disappearance is the most bizarre of all, horses were another American native that had absolutely dominated the Pleistocene grasslands. There are recently discovered horse kill sites in the West, but nothing on the scale of the Solutrean horse hunters of Europe, who left kill sites of 20,000 animals. Nonetheless, by 8,000 years ago horses became the last of the big a...