CHAPTER ONE

CHASING RABBITS

This rabbit thing is going to haunt us no matter where we go. Dogman F. B. “Happy” Stutz, “In California, Money Talked,” Greyhound Hall of Fame

Once Owen Patrick Smith created the mechanical lure, he had effectively set the stage for organized greyhound racing in the United States. Beyond its raw utility, his invention was also, in a sense, a cultural metaphor. His new device represented the influence of the nascent animal protection movement, which, at this point, chiefly espoused the ideology of kindness to animals and had far less to say about their “rights.” Substituting an electric rabbit for a live rabbit, if only on the racetrack, was a preliminary effort to lessen the element of “blood sport” in greyhound racing. Greyhounds still trained on live rabbits, but at least when in the public eye, a more respectable spectacle could take place. Certain blood sports were associated with the lower class, even though, paradoxically, coursing was rooted in an elite European practice, as were other field sports such as foxhunting. To the greyhound, however, the shift from live to electric lure was of no concern: anything in rapid movement was worth chasing. His instinct for hunting had long ago been cast into his DNA.

Well before greyhounds were employed as racers in the United States and later as common household companions, they had been valued for hundreds of years as hunters, often as sight hounds used to chase jackrabbits, although their prey included coyotes, antelopes, and other larger fleet-footed wildlife.1 The greyhound was first introduced to the Americas when Spaniards seeking land, gold, and glory arrived with their greyhounds and mastiffs. These dogs sometimes accompanied the conquistadors and were used to intimidate and kill indigenous people during violent raids. When compared with present-day representations of racing greyhounds, which often picture them in varying positions of benign slumber, Theodor de Bry’s early engraving of hounds attacking Indians (perhaps after a “chase”) shows the startling distance the greyhound has come in American consciousness.2 From a vicious, killing beast to a gentle household pet, the greyhound has occupied positions of absolute polarity in American history.

Differing viewpoints exist about the origin of the greyhound, with new DNA evidence casting doubt on old theories. The breed was long believed to have been used for hunting activities in ancient Egypt and possibly Mesopotamia, and to have reached Italy and Greece via the Middle East between 400 BCE and 100 CE. Now, however, greyhounds are thought to have relatively modern origins and were likely bred from more northern stock than North African sight hounds such as the Saluki.3 Early examples of coursing can be somewhat difficult to distinguish from hunting. The Greek historian Xenophon (431–349 BCE) penned the first known treatise on hunting, but he does not mention coursing with sight hounds. Arrian, however, an ethnic Greek writing more than 500 years later during the height of the Roman empire, wrote specifically about this practice.4 For many centuries to come, purists who embraced coursing followed his advice: “The true Sportsman does not take out his dogs to destroy the Hares, but for the sake of the course, and the contest between the dogs and the Hares, and is glad if the hare escapes.”5 Coursing enthusiasts have long made it clear that the kill was not the purpose of the competition.

Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) was a fan of coursing, as were other members of the aristocracy throughout England in her time. One chronicler noted that her endorsement and participation gave coursing “a degree of fashion and celebrity previously unknown,” with many following her lead and practicing the sport with “undiminished zeal.”6 The queen called upon her earl marshal, Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, to institute rules of coursing, most of which were then followed for centuries. During her reign, greyhound breeders “jealously preserved the secret of how their dogs were bred, and rarely, if ever, allowed a stranger to mix the blood of his kennel with theirs.”7 The link between the aristocracy and greyhound ownership continued for centuries in England. In his 1908 essay on coursing, British sportsman Ainsty noted that the possession of a greyhound was “considered as the mark of a gentleman” in England well into the nineteenth century.8

In fact, the sport had been popular among the upper classes in the British Isles (and beyond) long before the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Before coursing was codified, William the Conqueror (ca. 1028–1087) had enacted forest laws that restricted greyhound ownership. Such laws tightly regulated sport hunting by dictating that only certain classes could own and hunt with their dogs. As H. Edwards Clarke succinctly puts it, “Forest Laws were . . . born of this conflict between king and nobles hunting for pleasure and sport and the lower orders hunting for the pot.”9 Later, the Game Act of 1671 even limited who could kill a hare, firmly establishing hare coursing (and hare hunting) as an upper-class pastime.10

“Coursing with Grayhounds,” from the Gentleman’s Recreation, 1686, drawn by Richard Blome, and reprinted in 1911 in British Sports and Sportsmen. (UNLV Libraries, Special Collections)

Public coursing in England began during the reign of Charles I (1625–1649).11 The sport continued to develop and expand, with royal estates and baronial manors conducting coursing events in rural settings.12 In 1858 the National Coursing Club was established in England along with codified “Rules of Coursing” largely based on the Duke of Norfolk’s standards.13 Following the example of the Jockey Club in England, coursers registered their greyhounds in a stud book in order to document the purity of their breeding.14 The Waterloo Cup became the most famous prize awarded to coursers in Great Britain.15

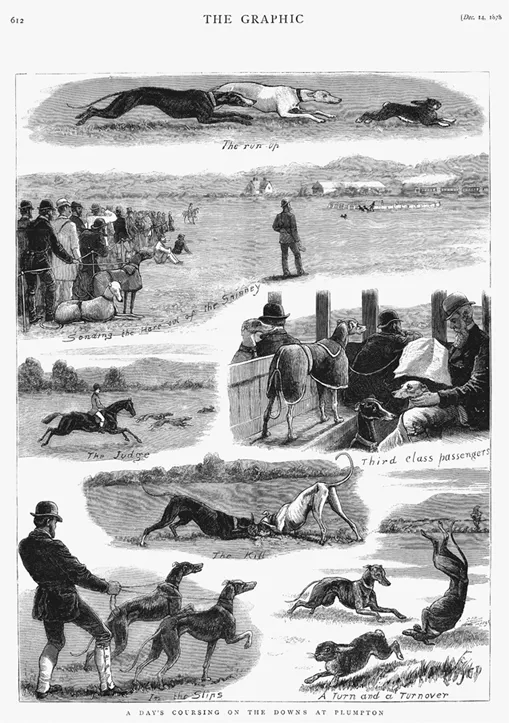

By this time coursing had evolved from a hunting competition into a carefully regulated contest in which two greyhounds chased a hare in an open field. One dog was judged to be the superior courser according to a set of established rules. The greyhound that killed the hare was not necessarily adjudged the victor; in fact, the purpose of the match was to showcase superior agility and running prowess rather than the raw ability to kill. As one enthusiast succinctly explained, “The dogs’ object is the death of the hare; the courser’s object is to test the relative speed, working abilities, and endurance of the competitors, as shown in their endeavours to accomplish their object. . . . The possession of the hare is of little consequence, except to the pothunter . . . who is quite out of the pale of genuine coursing society.”16 Greyhounds hunt by sight rather than by smell, and their most distinguishing characteristic is their remarkable speed: they are without question the fastest canines, able to achieve speeds of up to 45 miles per hour. But hares frequently prove to be the more agile of the two, thus creating quite a competition and a spectacle.

The growing popularity of coursing inspired English sportsmen to write about training techniques and other aspects of the sport. One expert noted in 1825 that the “training of the greyhound may be reduced to the same scientific rules as that of the race-horse.”17 In fact, the greyhound athlete was sometimes provided with elegant quarters, although perhaps not quite as grand as those provided for the thoroughbred. A number of Englishmen published treatises on the care of the greyhound athlete, most notably John Henry Walsh, who used the nom de plume Stonehenge.18 Stonehenge’s writings were later exported to the United States and quoted by numerous greyhound enthusiasts who followed. He boasted impressive credentials as an expert in field sports. Not only was he one of the original founders of the National Coursing Club in England, but he also served as chief editor of the London Field, a general sporting periodical, for more than thirty years. Some of his recommendations on training greyhounds, including the proper diet for the greyhound athlete, have proved to be long lasting. He ranked horse meat as the best option for feeding coursing hounds, a practice that continued well into the twentieth century in the United States.19

Early published discussions of coursing in England were infused with commentary about social class, especially as the sport began to attract wider popularity. Traditional open coursing had long been associated with the aristocracy. In 1886 the British greyhound enthusiast Hugh Dalziel argued in exclusive favor of this style of coursing, which did not permit fences or other barriers that could impede the chase. He was adamantly against closed coursing, which limited the competition to a fenced-in area, even though he noted with some surprise that there were, in fact, men of position who engaged in this form of the sport. He likened the hare in closed coursing to a creature coming out of a prison only to fall victim to men who sought “unearned increment.”20 Dismissing closed coursing as “effeminate Cockney coursing,” he argued that breeding greyhounds for coursing in small enclosures would destroy the most valuable qualities of the breed.21 He roundly dismissed the closed version as “a mere caricature of the ancient and noble sport, thus travestied for purposes of gate money and gambling.”22 Dalziel acknowledged that the ownership of greyhounds was slowly being diffused through all classes, attributing this change to the modification of game laws and the general increase of wealth and leisure time.23 The growth of railways and the increased activity of the press also led to wider participation.24 As coursing had continued to grow in England, the sport had gradually become more widely available to all classes in society.25 In fact, the tide had already started to turn well before the sport even reached the United States.

Even though coursing had long been popular in the United Kingdom, it was relatively unknown in the United States before the Civil War.26 Sportsman W. S. Harwood speculated in 1899 that private coursing started to gain popularity in the United States around 1850. Public events came later and were more strictly managed.27 The earliest coursing club in the United States, the California Pioneer Coursing Club, was established in 1867 by Clem Dixon.28 He preserved English rules but also adapted them to fit conditions unique to the state. Hares were abundant, and the prize of the competition was a trophy cup. There were no entrance costs for the contest; club members simply paid a monthly fee.29 In 1874 fifty members of the California Pioneer Coursing Club met to plan a fall match in Merced; the Merced Plains in the San Joaquin Valley, not far from Modesto, were said to be ideal for coursing.30 In addition, organized coursing began to flourish in San Francisco and in areas well beyond the state, such as St. Louis. The Occidental Coursing Club of Newark, California, was established in the 1880s and remained active throughout the 1890s. Coursing in California was sometimes practiced on open plains, but eventually closed coursing (often in parks) became the norm.

“A Day’s Coursing on the Downs at Plumpton,” from The Graphic, December 14, 1878. (Author’s Collection)

The sport of coursing rapidly acquired class associations in the United States. According to Joseph A. Graham, an authority on sporting dogs, enclosed park coursing was the fashionable Sunday sport in California in 1898.31 He praised coursing’s “ancient and honorable character and its association with the early aristocracy of sport” but noted that...