1

Stopping the Japanese Offensive

An Unexpectedly Large Commitment to an Unexpectedly Large War

For the United States, World War Two was really two conflicts waged simultaneously, one in Europe and North Africa against Germany and Italy, and the other in the Pacific Ocean and East Asia against Japan. Such a war required the dispersal of American resources and the careful allocation of priorities. To their credit, American policymakers had foreseen this possibility. Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor they had decided to give precedence to destroying Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime because they concluded that Germany’s economic, technological, and scientific capabilities posed the greater threat to the United States and its presumptive allies. War with Japan, if and when it came to that, would be a secondary concern addressed only after Germany had been defeated. And, in the grand scheme of things, this was more or less how it worked out. Most American military assets flowed across the Atlantic for use against Germany, which surrendered five months before Japan. The details governing the relationship between the two wars, however, were far more complicated and messy than they initially appeared. In fact, the Pacific War consumed greater resources than expected and developed in ways unanticipated by American military planners for several interrelated reasons.

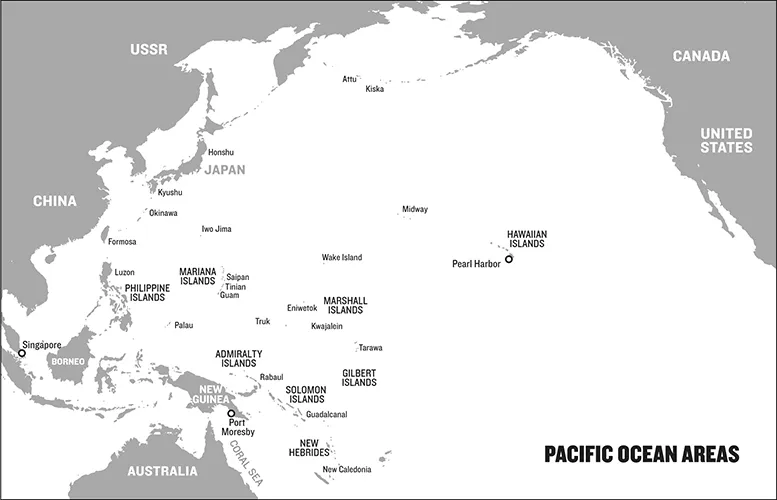

The Pacific War’s enormous geographic expanse provided one of these reasons. The Pacific Ocean covers approximately 64 million square miles, making it roughly half again as big as its Atlantic counterpart and more than twenty times larger than the contiguous United States. Although prewar American naval strategists expected to battle Japan roughly along the central Pacific axis from the Philippines to Hawaii, Japan’s initial multipronged offensive extended the zone of conflict far beyond that. As a result, the Pacific War was fought not only on and between the tiny and barren central Pacific atolls, but also in geographically and topographically diverse places such as the frozen and foggy Aleutians, the jungle-ridden islands of the Southwest Pacific, Manila’s urban environment, and the volcanic ash of Iwo Jima. The United States also committed significant resources, though few combat troops, to the Asian mainland in China, Burma, and India. The distances involved were staggering. It was 2,100 miles from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor, and from there an additional 3,400 miles to Tokyo, 4,770 miles to Manila, and 4,200 miles to Brisbane, Australia. By contrast, it was only 3,100 miles from New York City to London. New Guinea alone, the biggest of the thousands of islands dotting the Pacific, would if superimposed over the United States stretch from the North Carolina sounds to western Nebraska. Manning and supplying such a vast battlefield involving several fronts necessitated a greater commitment of American military resources than anyone predicted.

Logistics also forced the Americans to assign additional resources to the Pacific War. Not only were the distances involved huge, but the infrastructure in most places ranged from primitive to nonexistent. There were simply not enough airfields, port facilities, warehouses, power plants, paved roads, and so on that the motorized American military required to function properly. To support their activities, the army and navy brought in large numbers of service personnel to construct and maintain the necessary facilities, but they could never quite keep up with the logistical demands placed on them. At one point in early 1944, for example, more than 140 ships of all kinds crowded Milne Bay harbor in New Guinea waiting to be unloaded. Moving and caring for all these men, their supplies, and their equipment strained limited shipping resources that local commanders wanted to use to sustain their combat operations, and the problem only got worse as the Americans advanced across the Pacific toward Japan and stretched their supply lines even further.

Australia and New Zealand were two of the United States’ most important Pacific War allies. Australian troops in particular played a crucial role in stopping the Japanese offensive in the Southwest Pacific and bore the brunt of the fighting there until 1944. The two nations also provided significant logistical support for local American forces. Although both countries contributed to Japan’s defeat in vital ways, their participation complicated American military planning. Securing Australia’s and New Zealand’s communications and supply lines to the United States entailed a far greater resource commitment than American military strategists ever anticipated. Indeed, doing so initially required more men and material than the European War, which theoretically had top priority. The first ad hoc American counterattacks against Japan in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea were designed as much to safeguard Australia and New Zealand as anything else. Even after the Japanese threat there had receded, American personnel continued to stream into the region as further operations there developed a momentum of their own.

Competing interservice priorities also accounted for the Pacific War’s unexpected prominence. The Pacific Ocean’s peculiar geography—vast stretches of water sprinkled by thousands of islands of varying sizes—required close army and navy cooperation. The American military, though, was not a unitary actor. Instead, the army and navy were separate and independent branches constitutionally answerable only to the president as commander in chief. Fortunately, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) provided a coordinating mechanism for the two services. Created early in the war at Marshall’s urging, the Joint Chiefs consisted of Marshall, Army Air Force chief General Henry Arnold, chief of naval operations Admiral Ernest King, and William Leahy, a retired naval officer and former chief of naval operations who chaired the JCS meetings and liaised with the president. The JCS made decisions by consensus, which under normal circumstances might have resulted—and sometimes in fact did result—in gridlock and irresolution. The Joint Chiefs, however, had a powerful incentive to settle disputes among themselves. If they were unable to agree, their only recourse was to appeal to the president, but none of them wanted to abdicate their strategic responsibilities to the unpredictable Roosevelt, who on several occasions showed a positive genius for disrupting American grand strategy. As a result, many strategic judgments flowed from complicated compromises that worked to the advantage of those favoring a greater commitment to the Pacific War—meaning especially Ernest King. While Marshall was steadfast in his support for crushing Germany first, King was less so. King and many of his navy colleagues saw the Pacific War as their war. After all, they had planned for it for generations, and the Pacific’s wide oceanic expanses were ideal for the deployment of the navy’s fleets. Besides, naval officers were eager to exact retribution for the damage the Japanese had inflicted on their pride and ships at Pearl Harbor. King’s problem was that although he had the marines at his disposal for amphibious operations, it was soon apparent that the navy still needed the army’s help to prosecute the war against Japan effectively. King constantly pressured Marshall to divert more resources to the Pacific War. Marshall was willing to go along with King up to a point, first to stop the initial Japanese offensive and then to maintain the strategic initiative that American and Australian forces had so painfully seized. In return, King loyally supported Marshall in his strategic disputes with the British over the conduct of the European War.

These interservice rivalries manifested themselves in the conduct of the Pacific War as well. Army and navy officers often disagreed on the best strategic path to the Japanese homeland. Most naval officers, as well as a good many of their Army Air Force colleagues, advocated advancing on Japan via the central Pacific route from Hawaii. Doing so would give the navy plenty of space to maneuver its warships for the climactic battle that it sought with its Japanese counterpart. It would also provide the Army Air Force with the bases it needed for its long-range bombers to pound Japanese cities and employ the marines in their specialized role as amphibious shock troops against the small Japanese-held atolls in the area. Many army officers, on the other hand, backed the Southwest Pacific route from Australia. They argued that this approach would allow them to use Australia’s resources and manpower, afford them enough room to deploy their troops in the area’s big islands, sever Japan’s supply lines with the oil-rich Dutch East Indies, and reclaim American honor by liberating the Philippines. Both routes had merit, but the real issue was whether the army or navy would be in overall command of the Pacific War. As one general later put it, “I felt that the discussion really wasn’t basically concerned about the best way to [win the war]. It was who was going to do it, and who was going to be in command, and who was going to be involved.”1 The JCS was unable to conclusively settle the issue, so it instead compromised by dividing the Pacific War into two theaters, the Pacific Ocean Area (POA) under Admiral Chester Nimitz and the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) under General Douglas MacArthur, and authorizing each officer to conduct offensive operations. Although this resulting Dual Drive Offensive violated the American military’s emphasis on concentration of force, the JCS was willing to pay this price to preserve interservice harmony. Sanctioning the Dual Drive Offensive, however, required a corresponding increase in the amount of men, supplies, and equipment allotted to the Pacific War to sustain operations in both theaters.

Finally, the Japanese themselves compelled a larger-than-expected American investment in the Pacific War. Although the United States dwarfed Japan in economic productivity, racism and strategic myopia prevented American policymakers from recognizing Japan’s early military capabilities. Japan’s initial multi-pronged offensive netted it a quarter of the globe in six short months, and stopping it initially required American military planners to assign more men, supplies, and equipment to the Pacific than to Europe, where there was less immediate urgency for them. Once there, it was logistically and bureaucratically impossible to transfer all those assets across the Atlantic. Moreover, waging war against the Japanese proved more difficult than anticipated. As part of their Bushido code, Japanese servicemen saw surrender as dishonorable and often fought to the death. Prying them out of their well-defended positions entailed the overwhelming application of American firepower. Mustering and supporting such firepower, however, meant a massive commitment in manpower and materiel. Even worse, the Japanese battled with increasing ferocity as the American juggernaut approached their Home Islands, necessitating even more American resources.

For all these reasons, the American investment in the war with Japan was considerable. Indeed, because of the navy’s fixation with the conflict, nearly half of all American servicemen deployed overseas during World War Two went to the Pacific. The army did a better job of living up to the Germany First policy, but even it diverted substantial resources across the Pacific. By the time Germany surrendered in the spring of 1945, there were 1.36 million soldiers and airmen in the Pacific, about half as many as there were across the Atlantic.2 In terms of combat units, the army deployed twenty-one of its eighty-nine divisions, five of its twenty corps, and three of its eight field armies that saw significant action against Japan. Unlike in Europe, there were no army groups in the Pacific, mostly because Douglas MacArthur acted as his own army group commander.

Most of the combat units the army sent to the Pacific—fifteen of the divisions, four of the corps, and two of the field armies—spent the bulk of their time in action in MacArthur’s SWPA theater. Marshall permitted MacArthur considerable leeway in selecting his field army and corps commanders. Whenever Marshall dispatched a new field army or corps headquarters to SWPA, he usually gave MacArthur a list of possible commanders to choose from, and almost always mentioned his favorite based on his criteria. MacArthur might or might not accept Marshall’s suggestions, but he rarely asked for an officer by name from the States, perhaps because after retiring from the army in 1937 he simply no longer knew the eligible and available high-ranking personnel. Instead, MacArthur usually preferred to promote from within SWPA because he was more familiar and comfortable with those officers who had served with him there. He and General Walter Krueger, head of the Sixth Army and MacArthur’s chief ground forces commander, picked their corps commanders from those divisional leaders who had proven themselves as skillful and aggressive officers in independent offensive missions. In the rest of the Pacific, on the other hand, Marshall generally appointed the field army and corps commanders after consultations with General Millard Harmon and General Robert Richardson, the army’s highest-ranking officers in the central and southern Pacific.3

History has all but forgotten the Pacific War’s field army and corps commanders, in large part because of the long shadow that MacArthur cast over everyone and everything associated with the conflict in that part of the globe. At first glance the caliber of these men seems lower than that of their European War counterparts. Although many have heralded MacArthur as a strategic and operational genius, most of his army subordinates demonstrated little imagination at the tactical level. They frequently resorted to set-piece assaults that relied on massive firepower to overcome Japanese defenses. It is, however, important to place their collective record in context. In his mania for self-promotion, MacArthur intentionally denied his generals the kind of publicity that other theater commanders accorded their subordinates. As a result, the press rarely noticed even exceptional performances by most Pacific War generals. Moreover, American field army and corps commanders usually did not have the opportunity to engage in the kind of swift and sweeping flanking and exploitation maneuvers that sometimes characterized the European War because of the Pacific Ocean’s geographic, climactic, and logistical constraints. Pacific War generals may have been conventional and solid rather than dazzling and slashing, but they got the job done despite tenuous logistics, dissension within MacArthur’s military family and with the navy and marines, and stiff Japanese resistance. None was relieved due to incompetence, and one of the corps commanders went on to lead a field army before the war ended. While it is possible to criticize individual actions, these men never lost a major battle on their amphibious march to Japan.

Douglas MacArthur’s World

On the evening of 21 March 1942, a curious crowd in Adelaide, Australia, turned out to meet a train carrying the United States’ most famous general. Douglas MacArthur’s unlikely presence Down Under resulted from a series of unhappy and unforeseen occurrences. Just ten days previously he, his wife and young son and amah, and selected staff officers had on President Roosevelt’s orders slipped away from the besieged island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay on a PT boat. After a harrowing 500-mile journey through enemy-infested waters to the southern Philippines island of Mindanao, they boarded a ramshackle B-17 Flying Fortress bomber for a dangerous flight to Alice Springs in remote central Australia. From there they took a train to Melbourne via Adelaide. Along the way MacArthur learned that the American reinforcements he had expected in Australia were not there. Without them, there was no way he could rescue the beleaguered soldiers he had left behind—or, as some claimed, abandoned—in the Philippines. Exhausted by the strain of his long and dangerous journey, and burdened by his growing realization that he had played a major role in what was shaping up to be one of the biggest military defeats in American military history, MacArthur was depressed and discouraged by the time his train pulled into the Adelaide station. He was, however, not the type to flinch in the face of adversity. After greeting the assembled onlookers, MacArthur pulled a rumpled sheet of paper out and in a subdued, flat, and quiet voice read one of World War Two’s most famous speeches, in which he concluded, “The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines and proceed from Corregidor to Australia for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary object of which is the relief of the Philippines. I came through, and I shall return.”4

For all of MacArthur’s grim determination, the fact remained that the United States had suffered one military disaster after another in the first months of the Pacific War. Japan’s unexpected attack on the naval base at Pearl Harbor on the morning of 7 December 1941 crippled the American fleet there and temporarily removed it from the strategic chessboard. By the end of the year, the Japanese had also stormed Guam and Wake islands, isolating the Philippines from Hawaii and the American mainland. Roosevelt had recalled MacArthur to duty the previous July to command all the American and Filipino troops in the Philippines. MacArthur’s claims that he could successfully defend the archipelago helped persuade Marshall to send reinforcements there before war broke out, but things had not turned out as MacArthur planned. Hours after the Japanese raided Pearl Harbor, they also surprised MacArthur’s air force and destroyed most of its planes on the ground. On 22 December, Japanese soldiers landed at Lingayen Bay on Luzon and rapidly drove MacArthur’s ill-trained and -equipped American and Filipino soldiers out of Manila and into the nearby Bataan Peninsula. Although MacArthur’s men fought valiantly, the 76,000 troops on Bataan surrendered on 9 April 1942, followed by the capitulation of Corregidor and the rest of the Philippines on 6 May. These American defeats were bad enough, but they were just one part of an unhappy Allied tapestry. The Japanese also seized the oil-rich Dutch East Indies, Hong Kong, Burma, Malaya, and, perhaps worst of all, Singapore and its 65,000 British Empire defenders. Through skillful fighting and with minimal losses, the Japanese controlled one quarter of the globe by the end of May 1942.

Nine days after MacArthur made his celebrated speech, the Joint Chiefs of Staff put him in charge of the newly created Southwest Pacific Area theater. In doing so, the J...