![]()

1

“The Wolves We Saw Them

Everywhere”

“Beast Gods” and “Varmints”

In the summer of 1824, a young Missourian named James Ohio Pattie accompanied his father, Sylvester, as he led a large trade caravan toward Santa Fe, New Mexico, from the vicinity of what is now Omaha, Nebraska. On the night of August 6, the party, which had been working its way along the Platte River, arrived “at a village of Pawnee Loups,” with whom they remained for several days. In the midst of the visit, a band of warriors returned from a successful foray against a rival tribe. “A day or two after their arrival, they painted themselves for a celebration of their victory, with great labor and care,” Pattie wrote. “The chiefs were dressed in skins of wild animals, with the hair on. These skins were principally those of the bear, wolf, panther, and spotted or ring tailed panther. They wore necklaces of bear’s and panther’s claws.”1 Clearly impressed by the Pawnees’ ornamentation, Pattie would soon have occasion to collect skins and claws of his own. He would spend much of the next six years as a hunter and trapper in the Southwest and have numerous tense moments with grizzly bears. Whether the young man could fully appreciate the deeper spiritual meanings of the Pawnees’ accoutrements is impossible to know.

Pattie was in the vanguard of American westward expansion, during which bears, wolves, and “panthers” would be defined primarily in economic terms, as sources of profit in some cases and as obstacles to profit by most. Culturally, Americans of Pattie’s era and for generations to come perceived wild carnivores within a fearful context of difference.

For Native Americans such as the Pawnees with whom Pattie camped, similarities, rather than differences, defined their relationships with predators. Wolves, bears, and cougars, along with deer, elk, moose, and other animals, functioned as totems for special societies, clans, and tribes. They were typically understood as “people” in their own right and as relatives.2 The predator served western tribes and clans in a variety of roles, including that of a guide in the process of learning essential skills in hunting and warfare. At least some of the “Pawnee Loups” James Pattie witnessed celebrating their victory were possibly members of an elite society of warriors known as Wolves (loup being French for “wolf”; the Loup River system drains into the Platte River in eastern Nebraska). These distinguished Pawnees exemplified the endurance and furtiveness of the animal. Pawnee scouts or horse thieves imitated wolves by covering themselves in white blankets, moving about on all fours, and sitting on their haunches. Neighboring Plains tribes, occasionally the victims of the “Wolf People,” claimed that from a distance, they were unable to distinguish Pawnee raiders from real wolves.3

The guidance provided by a top predator had significant practical benefits for people dependent on the hunt and in stiff competition for territory and resources with rivals. On a symbolic level as well, predators assumed enormously consequential meanings for individuals, clans, and tribes. In much Plains Indian cosmology, the four cardinal directions were represented by Bear (west), Mountain Lion (north), Wolf (east), and Wildcat (south). The Pueblos likewise associated “Beast Gods” with the four cardinal directions as well as the worlds situated above (zenith) and below (nadir). Wolf guarded the east door—where time began—imparting hunting skills, curing illness, and protecting the prey animals upon which the people relied. Mountain lion shrines constructed between 500 and 800 years ago in present-day New Mexico demonstrate the importance of the big cat as a totem for the Pueblos as well.4

Generally, the powers and personae of bears, mountain lions, and wolves reflected the respectful attitudes Native Americans had toward these animals. Killing predators, for whatever purpose, required reverence for the hunted. A different and complex relationship applied to coyotes, which appear as trickster figures in a multitude of Native American tales. By turns creator, culture hero, coward, cheat, fool, seducer, shape-shifter, and thief, among other guises, Coyote figures embodied the complex and dualistic nature of human character in much western tribal mythology. Coyote stories entertained but also taught a people about their origins and identity; they provided lessons about proper behavior and decorum through the mirror image of a flawed but vital character. Despite all of his foibles, principally unrestrained desires for power, food, and sexual gratification, Coyote created the Indian people according to many emergence stories.5

When addressing how the indigenous peoples of the American West perceived and treated predators—in either mythological or historical terms—we need to be as cautious as hunters approaching a grizzly bear’s den. Conditioned by animated Disney features and other one-dimensional portrayals, we may be tempted to settle into romanticizing all Native Americans at all times as uniquely attuned to the natural world, as brothers and sisters to the four-legged creatures that sustained them both spiritually and physically.6 It is not as simple as that, but it is accurate to generalize that American Indians coexisted rather comfortably with predators. Appreciation, honor, and respect typified their responses to bears, cougars, and wolves. Yet fear remained as a genuine and reasonable reaction to what were indeed potential threats to any individual’s livelihood and even survival. Entwined as they were with predators—and with all animals and, in fact, all products of creation—in a unified world, the first peoples of the West possessed little apparent desire to “control” these animals.7

For Europeans and their American descendants who entered the West between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the need to control those animals commonly derided as “varmints” was not up for debate. In the millennia leading up to contact with the New World, Europeans had also developed complex relationships to predators, as evocative and rich in mythological and ceremonial import as anything found among Native Americans. Yet the more salutary views concerning predators had largely disappeared in Europe by the time settlement in North America began. The transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture and livestock herding, starting between 10,000 and 13,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent and gradually spreading west, altered human relationships with predatory animals in a fundamental sense. By necessity, caring for domestic animals dictated a hardening of attitudes toward carnivores. Western societies developed a wary perspective on nature and wild animals, which were increasingly seen as opposing forces to be confronted and controlled rather than as integral parts of an organic whole inclusive of human activities.8

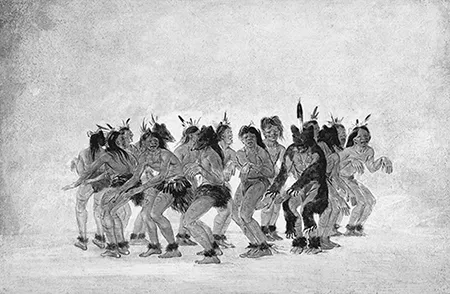

Bear Dance, Preparing for Bear Hunt, painted by George Catlin, based on sketches made in 1832 of a Sioux bear dance near Fort Pierre. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.

Agricultural and pastoral societies’ ambivalence about nature and wilderness was further reinforced by the spread of Christianity. In short, biblical sanction for humans’ dominion over beasts clashed with an alternative Western tradition of the wilderness as a sanctuary for the soul, a retreat from sin and temptation. Generally, Europeans lived in a religious culture that associated the wilderness and carnivorous animals with demonic forces intent on pulling souls away from God. In broadest terms, the Europeans who ventured to North America had long since abandoned an organic view of interdependence with nature, steeped in myth and ritual, in favor of a more confrontational approach based on economic forces and religious belief.9

For predatory animals, then, European entry into the New World would launch five centuries of constant struggle to adjust and survive against a determined competitor conditioned to destroy them on sight. In the first English colonies, a belief in human superiority and dominion over animals as both natural and divinely mandated trumped older folkloric traditions that, like Native American beliefs, might have attributed spiritual powers to animals. Key to the European colonists’ conflicts with predators as well as Native Americans were the competition for game, especially deer, and the vulnerability of roaming livestock due to declining numbers of game animals. Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the first bounties on wolves in 1630. Then, as later, the bounty system was rife with complications and opportunities for deception and fraud, and it was often thwarted by the wolves’ ability to adapt, survive, and recover lost population. Ultimately, however, the English colonies—or their successor American states after 1776—exterminated wolves and did their best to wipe out bears and panthers.10

The first encounters between Europeans and predators in the West were recorded by Spanish explorers. The chronicler of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s expedition into New Mexico in the early 1540s referred to sightings of “large numbers of bears,” cougars, and wildcats. Coronado’s massive train of men, horses, and livestock also surged into present-day Kansas, wherein, according to the travelers, “there are very great numbers of wolves on these plains, which go around with the cows [bison]. They have white skins.”11 A priest chronicling Sebastian Vizcaíno’s expedition to Monterey Bay in the winter of 1602–1603 noted grizzly bears feeding on a whale carcass. When Spanish authorities extended settlement and mission building to California more than 150 years later, additional information about the province’s bears entered the historical record.12

Problems with bears and mountain lions preoccupied California’s ranchos, which were the products of a few extensive land grants given to the colonial elite by the Spanish crown. An even more generous dispensation of ranchos after establishment of the Mexican Republic in 1821 added to the pressure on regional fauna. The introduction of free-ranging cattle had the predictable effect of causing bears to shift their diet from wild game, and large ranchos reported hundreds of cattle lost to bears each year. Multiple sources reported that some grizzlies would actually lure tragically curious cattle by lying on their backs in tall grass, rolling about and waving their paws in the air. Spanish authorities even dispatched soldiers from nearby presidios on preemptive campaigns against bears to further protect mission and rancho herds, typically to no avail. Grizzly populations, thriving on an abundance of livestock and undeterred by the relatively small human population, actually soared in California during the Spanish and Mexican periods. Rancheros and their hired hands, the vaqueros, developed a heart-pounding sport of lassoing bears from horseback with rawhide lariats, known as reatas. Once captured, many California grizzlies became participants in gory public spectacles pitting them against wild bulls.13

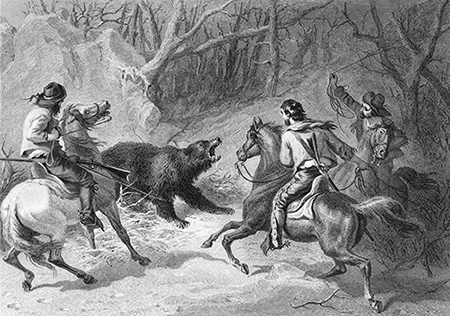

Native Californians lassoing a bear, ca. 1873. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California–Berkeley, Robert B. Honeyman, Jr., Collection of Early Californian and Western American Pictorial Material. BANC PIC 1963.002:1435 (variant)—B.

To the north, French Canadian, English, and Russian trappers in the eighteenth century had the occasional dangerous encounter with carnivores, and they procured a few wolf and bear hides to supplement profits from beavers and other furbearers. American awareness of the West’s extraordinary fauna officially arrived with Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s Corps of Discovery expedition between May 1804 and September 1806. In addition to antelope, bison, elk, prairie dogs, grouse, rattlesnakes, and other unique animals, the captains and some of the rank-and-file members of the corps noted the seemingly constant presence of wolves and coyotes. Expedition hunters, as recounted by Clark, bagged “a Small wolf with a large bushey tail” north of present-day Chamberlain, South Dakota, on September 17, 1804. This was the Americans’ first experience with a coyote, referred to in subsequent Clark journal entries as a “prarie wolf.” “The large wolves are verry numourous,” Clark also noted, and a few weeks later near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota, he again wrote of “great numbers of wolves” that “follow the baffalow and devour, those that die or are Killed, and those too fat or pore to Keep up with the gangue.” For the most part, the expedition had few serious confrontations with the furtive wolves and coyotes, although at one point, Lewis commented on the persistent threat of wolves to the corps’ meat supply.14

Expedition members had far more concern for life and limb when encountering grizzly bears, an animal theretofore unknown to American naturalists.15 The first direct contact with a grizzly was on October 20, 1804, near Bismarck, when Private Pierre Cruzatte wounded one and then dropped his gun while running away, an experience that would be repeated by corps members with some frequency. Lewis shot, wounded, and then killed a young male grizzly bear, which he referred to as a “yellow or brown bear,” in April 1805 while the expedition worked its way up the Missouri after spending the previous winter with the Mandan tribe. Lewis contrasted grizzlies to black bears, with which he and other expedition members were more familiar, finding them a “much more furious and formidable animal [that] will frequently pursue the hunter when wounded. . . . It is astonishing to see the wounds they will bear before they can be put to death.” A week later, Clark and one of the men killed a much larger bear, and Lewis marveled at the tenacity with which it fought for its life despite absorbing ten musket balls. The portion of the river east of Great Falls, Montana, seemed to be crawling with grizzlies, and as the adventures piled up, Lewis noted that “the curiossity of our party is pretty well satisfied with respect to this animal . . . the difficulty with which they die when even shot through the vital parts, has staggered the resolution [of] several of them, others however seem keen for action with the bear.”16

On balance, the Lewis and Clark expedition was harder on bears than the bears were on any of the men running frantically from those they shot. The journals demonstrate a reflexive response at nearly every sighting of a grizzly: take gun in hand and give chase. In practical terms, successfully hunting bears resulted in additional meat for the expedition as well as valuable oil and hides. In part, prudence also dictated an aggressive stance, for the bears seemed to be everywhere along the Missouri and came close to mauling several of the men. As the corps toiled in preparation for an arduous portage around the Great Falls two weeks after his close call, Lewis complained that “the White bear have become so troublesome to us that I do not think it prudent to send one man alone on an errand of any kind, particularly where he has to pass through the brus...