1 | PROGRESSIVE POLITICS, 1909–1910 |

Teddy, come home and blow your horn,

The sheep’s in the meadow,

The cow’s in the corn.

The boy that you left to tend the sheep,

Is under the haystack, fast asleep.

—Life, 19101

The key events that shaped the outcome of the 1912 race for the White House commenced almost as soon as the 1908 election was over. On 3 November 1908, the Republican candidate, William Howard Taft, defeated William Jennings Bryan. The Democratic nominee had now made his third unsuccessful race for the presidency. Despite the later perception that he was not a strong vote getter, Taft forged a decisive victory. He received more than 7,675,000 votes to some 6,400,000 ballots for Bryan. In the electoral count, Taft amassed 321 votes while Bryan garnered 162. The number of Americans casting their ballots rose some 1,367,000 over the 1904 result. Estimates were that on Election Day, 65.5 percent of the eligible electorate turned out.

It was the fourth consecutive presidential election victory for the Grand Old Party. In many respects, the 1908 contest resembled the struggles between William McKinley and Bryan in 1896 and 1900. Of the sixteen states that Bryan carried against Taft, he had won thirteen of them—eleven from the South plus Colorado and Nevada—twice before. Four years earlier the lopsided race of Roosevelt against Alton B. Parker had failed to bring Democrats to the polls. In 1908, Bryan increased Parker’s total by more than 1,400,000 ballots. At the same time, Taft saw his own count rise by 50,000 votes over what Roosevelt had amassed in 1904.

Other than Bryan, the most disappointed candidate was Eugene V. Debs of the Socialist Party. He had garnered 400,000 popular votes in 1904 and hoped to double his total in 1908. The party had raised the money to provide him with a campaign train, the Red Special, from which he had taken his message of an impending revolution to large, friendly crowds. Yet on Election Day, his result stood at just under 421,000 votes. The party’s message had not convinced the electorate as much as Debs hoped it would.

A signal feature to contemporary election observers was the ticket splitting that shaped the 1908 returns. In five of the states that Taft carried, including Indiana, Ohio, and Minnesota, Democratic governors won the statehouse. Since the polarizing election of 1896, partisan intensity had declined across many states. Even 65.5 percent was fourteen points down from the voter turnout in the first Bryan-McKinley contest in 1896. One hallmark of this period was the increasing suspicion about the value of political parties and their hold on the electorate. Roosevelt’s close friend Elihu Root, an eminent conservative, put the cause as “a growing irritation and resentment caused by the failure of party machinery to register popular wishes correctly and that conventions and legislatures give their allegiances first to managers and second only to the voters.”2 The next four years would see many calls to reform the rules of politics to give greater expression to the will of the people.

On Election Night, President Theodore Roosevelt was outwardly jubilant. “We have beaten them to a frazzle,” he said as the returns came in. His handpicked successor had trounced the Democrats. More important, as Roosevelt told an English friend, the voters had understood “that Taft stood for the policies that I stand for and that his victory meant the continuance of those policies.” Taft had been secretary of war in Roosevelt’s cabinet, and the president explained before his friend was nominated that “he and I view public questions exactly alike.” Thus all seemed to be coming up electoral roses for the Grand Old Party and Roosevelt.3

But the friendship of Roosevelt and Taft did not have a solid basis in real political agreement. A small gesture from Taft kicked off the process that ended in the bitter rupture between the two men three years later. Four days after the voting, Taft wrote the president a thank-you letter. He called Roosevelt “the chief agent in working out the present status of affairs” and then added a phrase that first irritated and later outraged his predecessor. “You and my brother Charlie,” Taft said, “made that possible which in all probability would not have occurred otherwise.”4

Charles Phelps Taft was the millionaire half-brother of the president-elect. His newspaper empire provided the wealth that had underwritten much of his sibling’s campaign. At the time, Roosevelt gave no sign that he had been offended. His correspondence with Taft continued in the usual friendly manner. But in Roosevelt’s mind the comparison stung. As he said a year and a half later, giving Charlie Taft and Roosevelt the same credit was like saying that “Abraham Lincoln and the bond seller Jay Cooke saved the union.” For Roosevelt, who liked to think of himself as an updated version of the Great Emancipator, no other words could have indicated how deeply he had been wounded.5

How could such a small incident initiate such large consequences? The problem was that, for all their surface rapport, Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft were not all that close in personality, attitude toward the presidency, and political philosophy. They had worked well together when Roosevelt was the chief executive and Taft a cabinet officer from 1904 to 1908. When their roles changed with Taft’s election as president, their underlying differences came to the surface. In a process that stretched over the next four years, their friendship turned to opposition and bitterness.

The president and his successor provided a vivid contrast in reputation and achievement in November 1908. The fifty-year-old Roosevelt was nearing the end of two terms in the White House that had made him an international figure. The people of the United States had watched his rise from New York politics through his exploits during the Spanish-American War to his accession as president after William McKinley’s death in 1901. For more than seven years, Roosevelt’s attacks on trusts, his wielding of a “big stick” in diplomacy, and his recurrent battles with Congress had dominated the headlines.

By the time he left office, Roosevelt had emerged as a political celebrity. He may have thought that he could be a private citizen again, but as his friend Elihu Root remarked, “He cannot possibly help being a public character for the rest of his life.” As an ex-president, he would be in the limelight, whether it was serving as a contributing editor for the Outlook magazine, hunting big game in Africa, or acting as the conscience of the reform wing of the Republican Party. He did not intend to seek a quiet retirement but rather expected to remain active in pursuit of a more just society.6

Whether in office or as a former president, Roosevelt exuded passion and vitality. His facile mind darted from issue to issue. He energized his followers and captivated the public. A sense of excitement followed him. His magnetism “surrounded him as a kind of nimbus, imperceptible but irresistibly drawing to him everyone who came into his presence—even those who believed they were antagonistic or inimical to him.” At the center of this personal electricity was a serious thinker who believed that the nation needed to adopt social justice reforms to avert violent revolution. Social justice, he believed, was a “movement against special privilege and in favor of an honest and efficient political and industrial democracy.” By 1909 Roosevelt sought to broaden the reach of presidential power and the role of the national government to engage these pressing needs.7

William Howard Taft, on the other hand, brought public geniality rather than charisma to the practice of politics. He was one year older than Roosevelt, and the race for the presidency was his first for major elective office. A Yale graduate and a lawyer by training, Taft had been a judge in Ohio, solicitor general of the United States, and a federal Court of Appeals judge before William McKinley tapped him to head the commission to provide civil government for the Philippine Islands in 1900. Taft then became governor-general of the islands. His strong performance in that job led Roosevelt to make him secretary of war in 1904. From then on, he functioned as a troubleshooter for the White House. Roosevelt once quipped that he had left the portly Taft “sitting on the lid” of potential trouble while the president was away from the White House on one of his many trips.8

When he searched for a successor in the run-up to the 1908 election, Roosevelt found that Taft was the logical choice. The secretary of state, Elihu Root, considered himself too old. Governor Charles Evans Hughes of New York struck Roosevelt as overly independent, and Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin had assumed a more radical stance on railroad regulation than the president. Searching, as he was, for a continuance of his legacy, Roosevelt turned to his friend Taft. He had been a loyal lieutenant in the Cabinet, was a resident of the crucial state of Ohio, and he seemed an ideological soul mate. By late 1906 and early 1907, President Roosevelt was Taft’s most enthusiastic booster.

Since they both needed each other, the two friends minimized their philosophical and political divergences. Roosevelt thought that the president should be able to push the boundaries of the Constitution to do good for the people. Taft believed that the chief executive should stay within the limits of the constitutional precedents. As a cabinet member, Taft chafed in private at his chief’s tendency to meddle in the affairs of the government departments. He liked the president personally but had less regard for Roosevelt’s more reformist associates in and out of government. Roosevelt thought Taft a good subordinate who would therefore become a strong leader. He never asked himself if he and the secretary of war really shared as many principles as he believed they did. Once their working relationship changed with Taft’s rise to the presidency, the two strong-willed individuals would find that they had very little in common.9

An erosion of their friendship marked the period of transition before Taft took office in March. The president-elect’s wife, Helen Herron Taft, and other family members advised him, “Be his own king.” In choosing his cabinet, Taft dropped some members of Roosevelt’s official family as he had every right to do. The problem was that Roosevelt remembered an earlier pledge from Taft to retain his cabinet. By the time that power passed to Taft, relations were very strained. An invitation from the Roosevelts to stay at the White House the night before the inauguration produced a very awkward evening that Taft later recalled as “that funeral.” So while all was pleasant on the surface as Taft became the next president, in private, tensions mounted.10

Roosevelt left three weeks after the inauguration for a hunting trip in Africa. He and his successor did not correspond during the next year. Each expected the other to write first. As time passed and the new administration moved further away from Roosevelt’s policies, the prospects for misunderstanding increased. On his safari, Roosevelt reached the conclusion that Taft had been a satisfactory cabinet officer but was not up to the task of governing the nation as president.

In office, Taft revealed a different governing style than the frenetic energy that had marked the Roosevelt years. The new president worked hard but had difficulty at first managing the flow of business. His personal secretary, Fred W. Carpenter, was in over his head and soon fell behind in his work. Lacking a good sense of public relations, Taft kept the press at arm’s length and did little to encourage favorable news stories out of the White House. He did not have Roosevelt’s sense of what pleased the public. Pictures of the president playing golf with rich men at exclusive clubs conveyed a sense that he was out of touch. A tendency to procrastinate in writing speeches produced some public gaffes. An unkind senator quipped that Taft was “an amiable island, entirely surrounded by men who know exactly what they want.”11

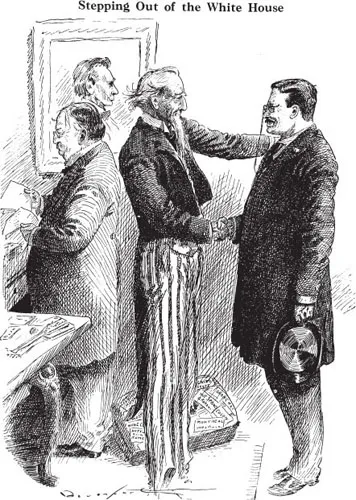

Uncle Sam congratulates Theodore Roosevelt at the end of his presidency as William Howard Taft prepares to assume the presidential duties. The actual transition was not as friendly as this image suggests. (Cartoon from the New York Evening Mail, 1909, in Albert Shaw, A Cartoon History of Roosevelt’s Career [New York: Review of Reviews, 1910])

Believing that his presidential role was to be a party leader who maintained GOP unity and helped enact their legislative program, Taft stressed working with the Republican establishment in Congress. Once he became identified with Nelson Aldrich, the dominant Republican in the Senate, and Joseph G. Cannon, the autocratic Speaker of the House, Taft raised suspicions among party reformers and friends of Roosevelt. In turn, the president resented opposition to his policies. He moved rightward toward his natural allies among Republican conservatives.

The nation over which William Howard Taft presided in March 1909 was in the midst of the period that historians have dubbed the Progressive Era. Since the end of the depression of the 1890s, the United States had experienced an age of political and social reform. In a series of campaigns to improve the quality of life, activists had sought an enhanced role for government at all levels in regulating business, supervising morality, and purifying the political system. Within the general consensus that the United States was a nation that God favored to set an example for the world, progressives, as they called themselves, argued that people were basically good. The right application of government support could make them even better.

Since the accession of Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency in September 1901, the impulse for reform had grown stronger. Roosevelt had placed his intense personality behind the idea that a more just society would prevent a social revolution and class warfare. Many middle-class Americans responded to this call. The reform elements within the Democratic Party, too, applauded parts of Roosevelt’s program and contended that even more regulation of business was necessary. The election of 1912 would be waged largely on domestic issues growing out of these concerns.

Unlike the 1890s, when hard times determined political responses, the political struggles leading up to 1912 occurred during an era of general economic prosperity. Since the presidency of William McKinley, economic indicators had much improved. The gross national product, which stood at an annual average of $17.3 billion between 1897 and 1901, would rise to $40.3 billion from 1912 to 1916. The average wage earner among the 95 million Americans brought in $592 per year in 1912, up from $454 in 1901. For that sum, the same individual worked fifty-six hours each week for a little more than 27 cents an hour. Ten years before, a comparable worker would have labored 58.7 h...