![]()

1SOVIET WARTIME EVACUATION AND ITS HISTORICAL CONTEXT

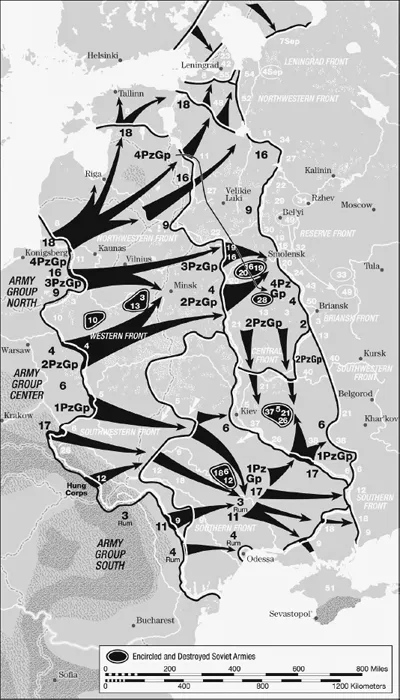

On Sunday, June 22, 1941, at 3:30 AM German artillery began shelling Soviet positions. Thirty minutes later, over 3 million German troops, supported by over 3,000 tanks and 2,000 warplanes, overwhelmed everything in sight along an 800-mile front stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Within hours, they had destroyed 1,200 Soviet planes, most of them still on the ground. After six weeks, the German Army had plunged deeply into the Soviet Union, killing or capturing almost 1 million troops. By mid-July, it had advanced within 322 kilometers of Moscow and 155 of Leningrad. In early August, enemy troops cut off Soviet access to the northern city by land, beginning a siege that would last for 900 days. Two months later, the enemy had advanced to within 32 kilometers of Moscow, encircling the capital on three sides. By now the invader occupied an area encompassing 40 percent of the Soviet Union’s prewar population, railways, and grain fields and half of its coal and steel production.

While many civilians stayed in territories overrun by the enemy, millions abandoned their homes for safer, they hoped, areas to the east and south. Because of the chaotic nature of evacuation and only partial registration of the many who fled, estimates of their number vary considerably, ranging from 16.5 million to 25 million.1 By the end of 1941, more than 2 million people had departed Moscow. By mid-April 1942, 1.25 million people, many of them children, had left the Leningrad region, 1 million from the city of Leningrad alone. With an influx of evacuees, the population of other cities increased dramatically. By the end of 1941, Omsk had grown by 42 percent, Kuibyshev by 36 percent, and Sverdlovsk by 28 percent.2 Kirov grew by one-third. Still more arrivals followed. As enemy forces advanced into southern areas of the USSR in the summer and fall of 1942, a second wave of evacuation followed in which 1 million departed from such regions as Voronezh and Stalingrad.

German advance on the Eastern Front. From left to right, territory seized by July 9, September 9, and December 5, 1941. Reproduced by permission from Glantz, David M. and House, Jonathan M., When Titans Clashed.

Factories moved en masse. Each month during the second half of 1941, an average of 165,000 railcars of industrial equipment rolled eastward.3 Estimates of the total number of evacuated enterprises range widely from 1,500 to over 2,600.4 As much as one-eighth of the nation’s industrial assets, including the bulk of its defense industry, relocated.5 Usually 40 percent of a factory’s workforce traveled with it.6 More than twenty commissariats, in whole or in part, departed from Moscow. Those for defense, foreign affairs, internal affairs, and transportation as well as the State Planning Committee (Gosplan) moved to Kuibyshev (Samara, before 1935 and after 1990), 867 kilometers southeast of Moscow. Other commissariats went to Kazan, Saratov, Astrakhan, Gorky, Smolensk, and Kirov.7 In October, much of the apparatus of the Russian Republic’s and USSR’s Sovnarkom and the Communist Party’s Central Committee left Moscow for Kuibyshev.

Thirty-five institutes of the USSR’s Academy of Sciences with their 4,000 scholars and scientists left Moscow. Moscow’s Tretiakov Gallery, Pushkin Museum, and Lenin Museum sent many of their valuable collections to safer locales. In July 1941, Leningrad’s Hermitage Museum dispatched to Sverdlovsk forty-five freight cars loaded with 2,538 crates containing 1.2 million items, among them paintings by da Vinci, Raphael, Rubens, Rembrandt, El Greco, and Repin. Moscow’s Lenin State Library shipped out 500,000 books and 7,000 manuscripts and Leningrad’s Saltykov-Shchedrin Public Library 350,000 books and manuscripts. Archives in Leningrad and Moscow and other locations west of the capital evacuated a substantial number of their collections. Movie studios, drama theaters, and orchestras relocated.8

A WORLD DISORDER

Wartime evacuation in the Soviet Union is only one of many episodes in modern history of the displacement of millions of people and thousands of institutions. It can best be evaluated in that context. That larger tale is one of considerable heroism and good intentions. It is also one of neglect, death by privation, and massacre.9 That story follows in considerable detail below, ugly and mind-numbing, and yet necessary, for precisely here the devil is in the gruesome detail.

From the sixteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century, colonial powers and the multiple states that they spawned forcibly transported 11 million Africans to the Americas. Perhaps as many as 10 percent of the “human cargo” died en route.10 At the same time, millions of natives in the “New World” suffered displacement and death. While slavery and the worst aspects of the treatment of Indians in the Americas ended by the twentieth century, cruel deportation and forced evacuations of people did not.

A tendency to regard the state as an ethnically homogenous unit meant, as Michael A. Reynolds has written in his Shattering Empires, an acceptance at the beginning of the twentieth century of “forced population exchange [as] routine practice, one that many regarded as logical and even salutary.”11 On the eve of World War I, the Ottoman government evicted 200,000 of its Greek subjects. A few years later, it deported more than a million Armenians, massacring many of them in the process. Following World War I, as a matter of choice and coercion, 1.2 million Poles left the lands of the former Russian Empire for the newly independent state of Poland and from 500,000 to 750,000 Germans left regions that now became part of Poland. At the same time, over 300,000 Lithuanians made their way to the new state of Lithuania. France expelled about 100,000 ethnic Germans from the newly reacquired provinces of Alsace-Lorraine. During the 1920s, following a redrawing of borders, Turkey and Greece exchanged about half a million Turks and a million Greeks. In the late 1930s, hundreds of thousands of refugees fled Spain, a country torn apart by civil war, to neighboring France.

On March 10, 1940, the German attack on Belgium and France set off the “Exodus.”12 Two million Belgians and 6 million French fled with what little they could pile in and on top of cars, bicycles, carts, and wheelchairs.13 On June 10, the French government vacated Paris. Four days later German troops occupied the capital, where little more than 20 percent of its prewar population of 5 million remained. In Lille, only 10 percent of its 200,000 inhabitants stayed behind. Cities receiving these citizens in flight doubled, even tripled, in size.14

Many of France’s refugees soon returned home. Other people deported by the German government before and after France’s defeat in 1940 could not. From its conquest of Poland in 1939 until December 1944, the Nazi regime relocated over 2 million Polish workers to Germany. At the same time, it brought more than 200,000 Germans from Poland and the Baltic states for resettlement in the Wartheland, an administrative district carved largely out of Poland and annexed by Germany. Most of these Germans, however, remained in camps until their subsequent transfer westward in 1944, along with hundreds of thousands of their fellow citizens fleeing the advancing Soviet Army.15 In the meantime, Germany and its allies sent to extermination camps and murdered there over 3 million Jews. They deported millions more to labor camps where many died from overwork and a lack of basic necessities. It should be added that in occupied territories, execution squads shot perhaps as many as 1.5 million Jews in and around the villages where they lived. (In addition, 1 million died from the horrors of ghettoization.)

With the war’s end, victorious allies forcibly deported Germans from East Central and Eastern Europe to a smaller and reconstructed Germany.16 At least 12 million were expelled, perhaps as many as 14 million.17 Germans were not the only people displaced. In September 1945, the Western allies and Soviet Union removed millions of other people from their homes.18 Across the ocean in the United States, many of the 120,000 Japanese Americans who had been forcibly relocated to concentration camps in the western parts of the country were only now beginning to return home.

Deportees everywhere died from starvation, unhygienic conditions, deliberate neglect, and massacre. Even when states were inclined to help with food, clothing, and shelter, a shortage of resources and the huge, often unexpected number of those in need overwhelmed the best of intentions. Between 1922 and 1932, Greece’s government assigned 40 percent of its budget to resettle its citizens recently expelled from Turkey. Yet that amount could hardly overcome their impoverishment, and the effort fueled popular resentment toward the new arrivals.19 Elsewhere, most refugees from the Spanish Civil War had returned home from France by 1940, but until then they had encountered a French government and population unable and, moreover, often unwilling to provide adequate shelter and nourishment.20

In the fall of 1939, millions of children were evacuated from English cities and towns to the countryside to avoid the perils of German bombardment. Many of them as well as their adult caretakers were not told of their destination and experienced a journey in trains some of which lacked toilets and seats. Foster families selected the arriving youths for their apparent capacity for agricultural labor. A small but nevertheless significant percentage of these children experienced mental and physical, including sexual, abuse.21

The following year, people fleeing in France’s “Exodus” met a mixed response from local governments and citizens, helpful in some towns and indifferent, even hostile, elsewhere. At war’s end, the expulsion of Germans, “a messy, complex, and morally compromised episode,” as its historian, R. M. Douglas has characterized it, involved beatings, rape, and starvation at the initial roundup, at transit camps, and in transport by foot or freight car to a newly constituted Germany.22 This “carnival of violence” took the lives of 500,000 “at the lower end of the spectrum, or as many as 1.5 million at the higher.”23 En route the living dumped corpses of the dead at each succeeding stop, the dead and dying “littering the platforms” of main line stations in 1945.24 In a Germany devastated by the war, local authorities and citizens, hardly in a position to help those expellees who did arrive, nevertheless responded as best they could. But once it became apparent that the new arrivals’ stay was not temporary, “local sympathy crumbled.” Farmers exploited the labor of those many refugees settled in rural locations.25 By comparison, across the ocean interned Japanese Americans had been reasonably well treated. And yet they experienced considerable loss of property and endured sparse conditions at the internment camps and the trauma that came with their ordeal.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, displacement, evacuation, and the cruelties associated with them have intensified. The combined forces of war, ethnic strife, political repression, famine, and failed states have at any given moment usually meant 25 million citizens forced to reside outside their own home country, a number, however, that has only recently doubled. More than half of these displaced people have come from Africa and millions more from former Yugoslavia, southeastern Asia, Afghanistan, the Caucasus, Ukraine, and the Middle East. In addition, each year there have been 10 to 12 million people labeled refugees, people uprooted from their homes but still residing in their own country.26

A TURBULENT EMPIRE

Soviet evacuation during World War II was neither the first nor the last massive displacement of people in the history of the Russian Empire and USSR. As many as 100,000 Crimean Tatars departed their homeland for the Ottoman Empire after the Russo-Turkish war of 1787–1792 and the subsequent establishment of Russian rule there. Many perished en route or after their arrival at destinations where their numbers defied efforts at assistance.27 About a half million people abandoned the Caucasus and 200,000 the Crimea during and after the Crimean War (1853–1856). Many left because of the destruction and expropriation of their property. Others, as Muslims, departed as a matter of choice to avoid governance ...