![]()

1

Life in a Small Town

The Culture of

Morenci, Arizona

In late September 1904, several members of the Sisters of Charity and others from the New York Foundling Hospital, accompanied by more than fifty orphans, gathered at Grand Central Station in New York City. The young children, ages three to six and most of Irish or Irish American descent, waited anxiously to board a train to take them to the territories of New Mexico and Arizona. The orphans were about to embark on a great adventure, one that ultimately would lead many to their new homes in southeastern Arizona and the town of Clifton and the mining camp of Morenci.1

After a week traveling to different locales to deposit children, the sisters and their staff arrived at the Clifton Train Station, just in the shadows of the lavender and gray mountains of the northern Sonoran Desert where prospectors had discovered valuable copper deposits in the late nineteenth century. Up the hills to the northwest a couple of miles lay Morenci, Clifton’s sister town. There, smelters belched out thick white smoke that reached high into the sky. Morenci’s miners toiled underground in extremely dangerous conditions, laboring in long shifts; many others slaved feeding the blast furnaces of the smelter. An abundance of work existed—but only for the hardy souls willing to risk their lives to harvest the copper.

At the train depot, a group of people waited for the arrival of the orphans. In the crowd stood expectant parents, all approved as upstanding Catholics by Father Constant Mandin, the local priest and recent immigrant from France. The women, many darker-complexioned Mexican Americans, looked anxiously at the new arrivals. Meanwhile, Anglo women congregated, drawn by the curiosity of the orphan train. Several became enamored of the little light-skinned children, and anger flared when they watched them being assigned to Mexican American parents from both Clifton and Morenci.

After the crowd dispersed, the Anglo women gathered together and began complaining about the fact that the Mexicans claimed the children. Rumors began circulating that the Mexicans had bought the children. And many of the Anglo women began to perpetuate the negative stereotypes of Mexicans as immoral, lazy, and drunken individuals who would endanger the orphans. Soon, a group of these women began pressuring their husbands and law enforcement officials to act to protect the children.

When local officials hesitated, arguing that they needed to follow the law and work through the courts, a vigilante justice prevailed. Many Anglos held animosities toward the Mexican Americans, particularly for the role they played in the 1903 strike ultimately dispersed by the US military. The Anglos also secured the blessing of the Phelps Dodge (PD) mining boss, Charles Mills, whom Mexicans called the patrón or mayordomo. He held the true power in the area, far more than even the local government representatives. In fact, in Morenci, the people had no city council, mayor, police chief, or any other officials. Mills embodied all three branches of government, and his word often constituted the law.

In a driving rainstorm on October 2, 1904, bands of armed Anglos, aided by some PD officials, spread out over Clifton and Morenci to round up the orphans. They appeared at the homes of the Mexicans armed with Winchester rifles and shotguns, beating on front doors with the ends of their guns to wake the occupants. Sleepy inhabitants cautiously opened the doors to find the well-armed Anglos demanding the children. Only in one case did a Mexican vigorously refuse to comply, but after a heated argument, even he relented. Ultimately, the vigilantes gathered with their wives at a local hotel and distributed the children to relatively prosperous Anglo families to raise as their own. Their work done with the complicity of Mills and the acquiescence of local officials, the vigilantes helped families start lives with their new children while many of the Mexicans, women in particular, grieved over their losses.

Representatives from the Catholic Church immediately complained about the kidnappings. The sisters from the Foundling Hospital contacted their superiors, who began legal proceedings to have the orphans returned to the Mexican American Catholic families. In January 1905, several children from Greenlee County, along with their parents, gathered at the Territorial Supreme Court in downtown Phoenix for a trial to determine who should keep the children. Journalists flocked to the courthouse to cover the case. Strangely absent from the subsequent coverage were Mexican Americans’ opinions in the affidavits and interviews that flowed from the proceedings. Fearing Anglo reprisals, they avoided both Phoenix and the publicity. Ultimately, with great fanfare, the Arizona Supreme Court upheld the seizures and the adoptions by the Anglos. The parents returned home in triumph with their children in their arms, heartily greeted by a large crowd at the Clifton Train Station.

One final obstacle remained, for the Foundling Hospital appealed the Arizona verdict to the US Supreme Court. But the high court proved equally unsympathetic. Justice William R. Day wrote in support of the Arizona decision, stressing that “the child in question is a white, Caucasian child … abandoned … to the keeping of a Mexican Indian, whose name is unknown to the respondent, but one … by reason of his race, mode of living, habits and education, unfit to have the custody, care and education of the child.”2 Thus ended the efforts to return the children to their Mexican American and Catholic guardians. The children became part of the local Anglo community.

The episode highlights several important characteristics in the history of Morenci and the region. First, the geographic isolation allowed the dominant Anglo socioeconomic groups, often in collaboration with PD officials, to become the law unto themselves. The Anglo vigilantes who kidnapped the orphans feared no retribution. A clear racial and class differentiation existed, which the company supported and sustained, partly to divide the labor force. Though some things changed by the 1960s, in many ways the community structures of the early twentieth century still existed as the Morenci Nine reached draft age in the mid-1960s.

* * *

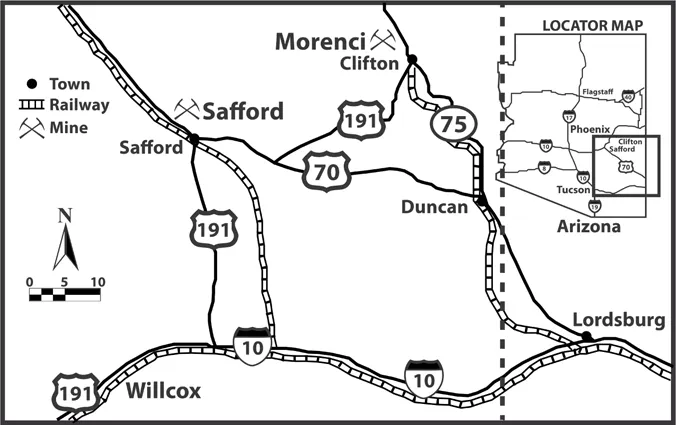

Like the social constructions of the area, the landscape of Greenlee County differed little in the mid-1960s from that of the early twentieth century, apart from the large open-pit mine that created a huge gash in the countryside and began swallowing the land in the 1930s. Located in southeastern Arizona, only about 20 miles from the New Mexico border and 60 miles from Silver City, Morenci rests where the Sonoran Desert ascends into the Apache Sitgreaves Forest, whose peaks ultimately reach over 11,000 feet. In the foothills lies Morenci (latitude 33.078 N and longitude ‘109.364), over 4,700 feet in elevation. Clifton sits down a thousand feet in the shadow of the peaks of the San Francisco Mountains, and the San Francisco River runs through the town and south toward the Gila River.

The environment that produced the Morenci Nine remains a dry (14 inches of rain in an average year), wild, and sometimes dangerous place. Author Barbara Kingsolver has observed that “everything in the desert is poisonous or thorned,”3 which is certainly true in Morenci, where creatures with fangs and razor-sharp teeth fill the canyons to the south. Deer and bighorn sheep populate the northern forest, and everywhere, jagged edges protrude from rocks and boulders, threatening all passersby. On paths, loose rocks and red dirt may look stable but can quickly loosen and send people tumbling down steep embankments.

The vegetation is equally inhospitable. Waist-high cacti (including the prickly pear variety) blend in with low-lying, often brown and gray scrub brush. The master of these plains is not the saguaro cactus that visitors view to the west around Phoenix and Tucson but the ocotillo. In many ways, this cactus represents the environment of southeastern Arizona, especially in the hills of the red clay canyons of northern Greenlee County.

The ocotillo resembles an octopus with its head buried in the ground and its tentacles extending stiffly upward into the air, sometimes reaching 10 to 15 feet. For most of the year, its tall, thin, and rigid limbs remain gray, and sharp, thick thorns protrude from the vines, cutting the flesh of the unfortunate person who stumbles into them. During the infrequent rainy periods, however, the plant becomes green and has beautiful orange and red flowers (ovates) sprouting atop the vines. Only robust plants such as the ocotillo survive in the harsh climate of the region, and much the same can be said of the people in this area.

Regional map of southeast Arizona. (Map courtesy of Freeport-McMoRan.)

The untamed wildness and rugged environment create a magical and alluring land that appeals to such hardy souls. To the south of Morenci, canyons cut through the red soil, and shallow rivers, such as the San Francisco and Gila, meander through them. Relatively fertile farmland sits farther to the southeast in the Duncan area, where Mormon farmers flourished and large ranches were established, including the Lazy B Ranch owned by Harry Day, father of the future Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor.4 To the north are millions of acres of national forest complete with tall pine and aspen trees, flowing streams filled with fish, cold-water lakes, and beautiful meadows that provide a welcome escape from the stifling summer heat. Outdoor enthusiasts love the area for hunting, fishing, and camping, as well as for the beautiful sunrises and sunsets and amazing vistas where one can see for many miles without detecting any real signs of human civilization.

The landscape and environment created a tough and prideful people steeped in western concepts of hard work, self-sufficiency, and rugged individualism. These people lived in relative isolation, far from the creature comforts that many identified with fast-paced city living, such as fancy restaurants and high culture. Males in the area traditionally led an industrial life but often envisioned themselves as outdoorsmen and hence in some ways as heirs to the frontiersmen. They enjoyed guns and hunting and a rambunctious lifestyle characterized by heavy drinking and hard-fought athletic competition on football fields, wrestling mats, and baseball diamonds. When combined with the type of work done by most in the mines and smelters, the personal character of the men in particular seemed well suited for military service, especially for the most physically demanding jobs in the military, including infantryman.

Although the natural environment helped shape perceptions of people and their place in the grand scheme of the world, a major factor that molded people in Morenci remained the mining companies. In the late nineteenth century, the promise of gold and silver attracted people from all over the world to the Arizona Territory. But the more sustainable prize became copper. Throughout the southern half of Arizona, extending from Bisbee and Douglas to Ajo and Jerome, copper became king. In the process, the Morenci-Clifton area became one the biggest producers in the world at a time when the demand for copper skyrocketed with the mass development of electrical power.

In southeastern Arizona, American entrepreneurs and settlers faced numerous obstacles and many hardships. The Apache tribes of the region resisted fiercely but ultimately signed a peace treaty that opened up the new territory, although periodic raiding by leaders such as Geronimo continued into the 1880s. The desert climate and starkness also proved daunting, although the promise of work and the possibility of making a fortune continued to draw robust souls into the area.

These included the Metcalf brothers, James and Robert, who in 1872 discovered copper outcroppings near present-day Morenci and established the Longfellow and Metcalf Mines. Investors began pouring in money to develop the abundant copper deposits, and they provided funds for building a railroad track to the nearest major line, located 60 miles away in Lordsburg, New Mexico. Over time, enterprising individuals such as James Colquhoun developed a leeching process that allowed for easier extraction of the minerals, and others built smelters that processed the ore. Miners and workers—Anglos, European immigrants, and Mexicans—rushed into the community of Morenci (named after a small town in Michigan). And with them came problems of lawlessness, disease, and a certain degree of anarchy. Nonetheless, by the turn of the twentieth century, several different companies had produced millions of pounds of copper and reaped huge profits.5

For Morenci, one company ultimately emerged as the principal force—the Phelps Dodge Company. The New York City–based corporation, working through its agents in the southwest territories, among them James Douglas, created a mining empire. In 1895, Douglas traveled to Morenci, where he quickly built up the existing operation and bought out competitors.6 For more than one hundred years, PD completely dominated Morenci. The massive enterprise became one of the largest in the world, moving from underground mining to a huge open-pit operation in 1937. One observer noted that by the early twentieth century, Morenci had become “a formal, legal company town, the provincial capital of a private kingdom.”7

Life in the company town differed from that experienced by the vast majority of Americans. Mining camps such as Morenci existed all over Arizona, Colorado, and Montana and also in the coalfields of Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and West Virginia. But the complete dominance exerted by PD separated the Morenci camp from other towns, even mining communities such as Globe and Bisbee, which still maintained some autonomy from PD. Democracy existed in Morenci only in a few forums such as the school board, but in reality, PD’s officials often superseded those organizations.8

Most mining camps resembled a corporate socialist state.9 The company provided the housing for workers, usually in dwellings that were the same color and size and offered the same amenities. In Morenci, these homes perched on the terraces that climbed from the center of town up the red clay hills. Most had two or three bedrooms, and they rarely exceeded 700 square feet in size. Company officials assigned the homes by seniority and race. Until 1969, PD segregated the town into sections, with Anglos living in several locations, Mexican Americans housed in New Town and Plantsite, and Native Americans occupying Tent City in the shadow of the always billowing smokestack that reached several hundred feet into the sky.10 Managers and other prominent members of the company, such as doctors, had larger homes, typically located on promontories overlooking the camps, a practice even continued today in new Morenci, where the elite live on what the workers call Snob Hill.

The starkness of the Morenci camp struck many people as they moved into the community or when they visited, even as late as the 1960s. One Irish priest assigned to the local parish in 1962, Eugene O’Carroll, remembered walking out of his house on the first day and then writing his mother, “I’m in a shanty in an old shantytown.”11 Another person traveling to Morenci observed that the town and the belching smelter constituted quite a sight: “The Dantesque image obtained—sulfur, slag, glaring heat, perpetual subterranean fires, roasted landscape … seem to fulfill the abomination of desolation of scripture.”12 Morenci took on an even more surreal appearance when the smoke of the smelter blew north into the center of town, leaving it blanketed in what one person described as like the wisp of white smoke produced by a firecracker exploded on a still night, except this wisp engulfed the entire camp.13

In Morenci, PD designed the town around the large Longfellow Inn and the Morenci Hall, the latter with its three full stories and archways and large verandas overlooking the camp. Church steeples dotted the landscape, representing all the major denominations, particularly southern ones such as t...