![]()

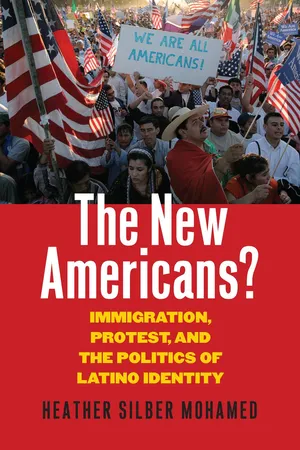

1 | “We Are America”

In December 2005, the US House of Representatives passed far-reaching legislation for immigration reform. H.R. 4437 (US House of Representatives 2005), also known as the Sensenbrenner Bill, contained a range of proposals that opponents viewed as highly punitive, including increased penalties for illegal immigration, expanded construction of a nearly 700-mile fence along the US-Mexico border, and classification of unauthorized immigrants and anyone helping them enter or stay in the United States as felons.1 As the Senate moved to consider its own immigration proposal, between 3.5 and 5.1 million people, mainly of Latino descent, protested across the country in an unprecedented demonstration of “Latino pride and power” (Félix, González, and Ramirez 2008; Janiot 2006; Oz 2006).

Yet, the language used at these events emphasized Latino pride in a unique way—by affirming that Latinos are part of America. At these protests, which are often seen as the start of the contemporary immigrants’ rights movement, participants advanced claims of belonging and citizenship in the United States (Rosman 2013). US flags were widely distributed and displayed, along with other patriotic songs and symbols. Protesters carried signs proclaiming “We Are America” and “Today We March, Tomorrow We Vote” (Fraga, Garcia, Hero et al. 2010; Oboler 2014; Pallares and Flores-Gonzalez 2010).

With their emphasis on inclusion and patriotism, these events contrasted starkly with earlier decades of Latino organizing, which typically highlighted differences with the Anglo majority. In 1994, for instance, California voters considered Proposition 187, a popular referendum that sought to deny undocumented immigrants access to social services. Across the state, the Latino community took to the streets to protest the referendum in mobilizations dominated by foreign flags and images and the Mexican flag in particular. After California voters passed the referendum, critics argued that these foreign images fostered a sense of ethnic threat among white voters, leading many who had been undecided to support the proposal (Martin 1995).2

A decade later, following a media backlash in which memories of the Proposition 187 vote were invoked, Latino organizers took a different approach to protesting H.R. 4437 (Chavez 2006; Pineda and Sowards 2007; “The Power of Symbols” 2006). Rather than emphasizing a distinct culture or community, the spring 2006 protests highlighted the commitment of Latinos to the United States as well as their claims of belonging in this country.

What led to this change in symbolic imagery? What effects did the protests, and their patriotic frame, have on Latino attitudes and self-perception? Also, what did this new identity mean? As Citrin and Sears (2014, 38) explain, “The choice of identities is often regulated by politics.” I build upon that idea by demonstrating how the debate over immigration policy, the protests that emerged in response, and their patriotic frame, or story line, reshaped Latinos’ identities as Americans. This book was written prior to the 2016 presidential election, in which Republican nominee Donald J. Trump brought questions of immigration policy and what it means to be American back into the forefront of US politics. The increased prominence and polarization of these discussions underscore the timeliness of the arguments made throughout this book.

The discussion over who counts as American, and whether “new” Americans should be created, defines the United States as a country as well as the boundaries for who is included in US society. At the most basic level, the federal government defines the categories of “us” and “them” through laws about citizenship and immigration. These regulations provide an objective definition of an American identity (Conover 1984; Huddy 2001). Yet, identities are also frequently subject to contestation, or debate, over their content and meaning (Abdelal, Herrera, Johnston et al. 2009). Thus, like other identities, an American identity can also be more subjective (Citrin, Reingold, and Green 1990; Citrin, Wong, and Duff 2001; Huddy 2001).

As in previous eras of US history, the immigration policy debate in the twenty-first century has created changing categories of “us” versus “them.” In earlier debates, questions of membership and inclusion have targeted a range of groups, including immigrants from Europe and Asia. In the contemporary debate, Latinos have become the new “them,” with questions of immigration and references to immigrants often seen as synonymous with Latinos in general and Mexicans in particular (Chavez 2008; Hero and Preuhs 2007; Newton 2008; Rim 2009).

In recent years, however, Latino leaders have worked hard to frame themselves as the new “us.” This book studies the effects of those efforts, evaluating the ways in which the immigration debate and responses around a particular frame can affect the broader process of Latino inclusion and political incorporation within US society. A range of existing research assumes the existence of an identity-to-politics link in which self-identification drives policy attitudes (Lee 2008). I view this relationship as more iterative. My theory develops the idea of a politics-to-identity link in which political debate and protest can influence self-identification in multiple ways, focusing specifically on the 2005–2006 congressional debate over immigration reform and the unprecedented wave of Latino protests that followed. My analysis offers a new view of the effects of the immigration debate on Latino self-identification. In so doing, I advance our understanding of the ways in which political debate and protest can influence public opinion and subjective perceptions of identity categories.

Accordingly, my book responds to recent calls for more research to better understand “the role of context in increasing the salience of national identity” (Huddy 2016, 14; see also Schildkraut 2014). To date, much of this research focuses on the influence of political context on the extent to which members of the majority group embrace a national identity. For instance, during times of increased threat—whether related to national security, racialized contexts, or tension over immigration—national identities become more prominent and more influential in shaping political attitudes (Davies, Steele, and Markus 2008; Falomir-Pichastor, Gabarrot, and Mugny 2009; Kam and Ramos 2008; Transue 2007).

With respect to minority groups, similar circumstances are thought to result in a reactive ethnicity in which individuals embrace an alternative “ethnic” identity rather than identifying with the majority group (Aleinikoff and Rumbaut 1998; Bean, Stevens, and Wierzbicki 2003; Massey and Sánchez R. 2010; Neckerman, Carter, and Lee 1999; Rumbaut and Portes 2001; Schildkraut 2005b). In contrast to existing explanations, this book explores the varied ways in which a context of political threat and social movement mobilization can shape Latino attitudes and self-perception. I ask whether, under certain circumstances, contentious policy debate and a hostile political context can lead a marginalized group to have increased feelings of inclusion rather than increased distance from the majority group. I address this question by examining Latino attitudes about immigration policy and self-identification before and after the 2006 protests.

My research also highlights an important paradox: Latinos have long indicated that they prioritize other policy issues, such as the economy and education, over immigration. Yet, the immigration debate is uniquely poised to mobilize a majority of the Latino population and to influence its political incorporation into the United States. I develop this idea while also studying the variation that underlies this paradox. Because the debate over immigration reform does not affect all Latinos equally, my analysis emphasizes intragroup differences within this population. For instance, Puerto Ricans are born US citizens regardless of birthplace, and Cubans have received preferential immigration status in the United States for decades, making immigration policy less salient for members of these national origin groups. The immigration debate is also less central to more established Latinos, such as those who are more acculturated or have been here for many generations (García Bedolla 2005). I find that distinct subgroups within the Latino population respond differently to the immigration debate and the 2006 protests, with the politics-to-identity link contingent upon issue salience.

Why Latinos?

The US Census defines a person as Latino or Hispanic if that individual is of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, and Albert 2011). As this definition suggests, Latino is commonly thought to refer to an individual’s ethnicity, considered separate and distinct from one’s racial category. Although race traditionally refers to skin color, ethnicity suggests a shared culture or experience and may include individuals of any race. For the Latino population, language and religion are two commonly cited indicators of this shared culture.

In 2003, Latinos officially overtook African Americans as the country’s largest minority group (Segura and Rodrigues 2006). At the time of the 2010 US Census, an estimated 50.5 million Latinos lived in the United States, constituting approximately 16 percent of the overall population. This figure represents a sharp increase from the 35.3 million Latinos counted in 2000; indeed, more than half of the total population growth in the United States during that ten-year period reflected growth in the Latino population (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, and Albert 2011).

As the Latino population grows, so too has this group’s potential to influence electoral outcomes. Between 1998 and 2008, the Latino share of the national electorate doubled, from 3.6 percent to 7.4 percent (Barreto and Segura 2014). In 2012, for the first time, Latinos constituted an estimated 10 percent of the national electorate (Lopez and Taylor 2012). High concentrations of Latino voters in key swing states such as Nevada, Florida, and Colorado have left this population poised to play a decisive role in the nation’s presidential election process. The Latino electorate was instrumental in contributing to President Barack Obama’s 2012 victory, with the candidates’ distinct positions on immigration policy significantly influencing Latino voting choices (Barreto and Collingwood 2015). Although this book was written prior to the 2016 presidential election, both the Latino electorate and the immigration debate remained central to that contest. Group members have also had a growing influence in local and state politics across the United States (Farris 2013) and in key US Senate and House races (Rodriguez 2012).

Yet, the extent to which the Latino population embodies a set of similar experiences, attitudes, and preferences in US society is less clear. Latinos in the United States hail from more than twenty different countries, representing vastly different historical and political backgrounds. Some arrived seeking economic opportunity, and others came as refugees from a bloody civil war, military takeover, or regime of single-party rule. Some have roots in prosperous democracies, whereas others have no experience with democracy and no understanding of the basic underpinnings of the US political system. Still others have ancestors who became Americans by conquest; for instance, through the acquisition of Puerto Rico in 1898 and territory originally belonging to Mexico in 1848. As will be discussed throughout this book, this diversity shapes the perspective through which individuals view US political life as well as attitudes about their identity as Americans and sense of belonging in the United States.

As the Latino population expands, it is also becoming ever more diverse. Table 1.1 illustrates the growth of the Latino population since 2000, focusing specifically on the five largest national origin subgroups. As this table demonstrates, Mexicans constitute almost two-thirds of the Latino community in the United States today and represent much of the overall growth within this population. However, other national origin groups are growing fast.

Between 2000 and 2010, the Salvadoran population in the United States increased by more than 150 percent, making this community among the fastest-growing national origin groups (Ennis, Rio-Vargas, and Albert 2011). Indeed, estimates from the 2011 American Community Survey suggest that Salvadorans may have surpassed Cubans as the third-largest national origin group in the United States, with populations of 1.95 million and 1.89 million, respectively. The Dominican population is not far behind, with an estimated 1.4 million living in the United States as of 2010 (Lopez and Gonzalez-Barrera 2013).3

Table 1.1 Change in Latino Population by Five Largest Subgroups, 2000–2010

Source: US Census Bureau (Ennis 2011)

For immigrant groups, experiences before coming to the United States significantly influence political attitudes and behavior upon arrival (Wals 2011). To the extent that existing research on Latino politics in the United States explores variation by national origin, much of this literature focuses on distinctions in attitudes and political behavior between the three historically large subgroups: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans (Abrajano and Alvarez 2010; DeSipio 1996a; Oboler 1995). The rapid growth of other national origin groups underscores the need to better understand Latino diversity beyond traditional populations, and particularly how group members’ varied experiences influence their identification as American and their political participation.

In addition to national origin, a growing body of research highlights intragroup differences based on factors such as language proficiency (Abrajano 2010; García Bedolla 2003), immigrant generation (García Bedolla 2005), and gender (Bejarano 2014; García Bedolla, Lavariega Monforti, and Pantoja 2007; Hardy-Fanta 1993; Jaramillo 2010; Jones-Correa 1998a). Immigrants have also moved into “new settlement areas,” adding additional geographical variation to this already heterogeneous population (Marrow 2005; Massey 2008).4 Demonstrating this rapid growth, between 2000 and 2010, the Latino population increased by more than 50 percent in the majority of states and by more than 100 percent in nine states, from South Carolina to South Dakota (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, and Albert 2011). Thus, questions relating to Latinos’ sense of identity as “new” Americans, their political participation via protests, and their incorporation into US society are increasingly national ones. With the contentious debate over immigration policy once again at the forefront of US politics, the distinct ways in which group members’ experiences interact with the heated rhetoric of the immigration debate hold important implications for the country’s political system and polity.

Outline of the Book

My politics-to-identity theory explores varying Latino responses to the 2006 immigration debate as well as the distinct ways in which this debate and ensuing protests influenced Latino political incorporation into the United States. Drawing on a range of primary and secondary accounts, the first part of this book presents important theoretical and historical background to support later arguments.

Specifically, Chapter 2 develops my politics-to-identity theory, incorporating scholarship on policy feedback, social movements, and framing. I also explain key elements of the research design used in later chapters, which employ data from ...