![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE CHINESE QUESTION

America in the mid–nineteenth century was racked by ambition and anxiety. Most people felt as if the burning of the nation’s capital by British troops was in the remote past, even though the War of 1812 had ended just a generation before. A rejuvenated and confident citizenry was pronouncing the message of manifest destiny to justify the formation of a continental empire. After promptly bluffing Great Britain and fighting Mexico, the expansionist United States cheerfully moved its western boundaries by the end of the 1840s from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast. Almost immediately the newly acquired territories began to generate more excitement and drama than the populace could have anticipated. No informed citizen could avoid engaging in the emotional conversations surrounding the nation’s conquests symbolized by the Oregon Trail, the California gold rush, the Compromise of 1850, and the transcontinental railroad. While Eastern lawmakers and entrepreneurs were contemplating how to genially incorporate this vast area into the Union, another big surprise came from the West: the influx of large numbers of adventuresome Chinese. Before this Asian migration to the American West, the population of the United States had been composed of racial groups with origins in Africa, Europe, Mexico, and Native America. Ethnic conflict rather than cultural diversity dominated the contemporary mind. The arrival of Asians further complicated the already troublesome racial discourse that had been draining much of the energy of the exuberant republic. In addition to debates on the peculiar institution of slavery and the “Indian problem,” Americans were now obliged to address the so-called Chinese question.1

On January 24, 1848, a week before Mexico officially ceded the northern half of its country to the United States, James W. Marshall, a carpenter at John Sutter’s New Helvetia in northern California, stumbled upon some gold flakes in the American River about forty-five miles east of present-day Sacramento. A simple assay confirmed his judgment and scared his boss, who envisioned the rapid destruction of his agricultural kingdom by a stampede of newcomers. Sutter decided to keep Marshall’s discovery secret for the time being. But his loose tongue and his employees’ big mouths made the task impossible. By the late spring, virtually every Californian had heard of “free” gold. Many had already overrun Sutter’s estate. The news quickly spread to the entire Pacific Rim. Before the end of 1848, Oregonians, Mexicans, Peruvians, Hawaiians, and British Columbians had converged upon El Dorado. People in the eastern United States, not convinced of the discovery of the coveted glistening precious metal until the late fall, followed on their heels. By early 1849, tens of thousands of Americans had headed for the West Coast by land or by sea. The “golden yellow fever” afflicted the native population as well as fortune hunters from England, Ireland, Germany, France, Spain, Australia, and Chile, all of whom joined the multitude of forty-niners.2

The first big reward for the forty-niners was freedom and equality. From 1848 to 1850, a U.S. military governor nominally administered California. Without a structured civilian bureaucracy, it was impossible for a few soldiers to control a huge international crowd. On the eve of the gold discovery, California had a non-Indian population of less than 14,000. The forty-niners boosted the population to nearly 100,000. By late 1852, about a quarter million people resided in the region. Nobody had heard of the provision in the Ordinance of 1785 that gave the U.S. government a royalty of one-third of any gold, silver, or other minerals extracted from the public domain. Everyone assumed that the gold was free. Most had no boss; few cared about rules. California’s unique circumstances, which included instant wealth, unlimited growth, and ethnic diversity, all arising in a political vacuum, would have a powerful effect on the state’s future. After the gold rush, California resembled no other place in the United States.3

Although stories of quick fortunes in California reached Hong Kong as early as the spring of 1848, the Chinese did not catch this American fever for a few years. Hoping to generate a shipping business in human cargo, British and American ship captains at ports in China zealously promoted the California “dream.” Local boosters also bombarded the people with exaggerated and misleading information. Traditional Chinese caution prevailed, however. In 1848, three Chinese servants to a ship captain did reach San Francisco. As soon as they landed in California, they learned about the gold rush, and each of them contracted the fever, becoming prospectors and initiating the first Chinese migration in the months and years to come. By no accident, these first prospectors soon enticed 325 risk-taking Chinese to join the growing numbers of forty-niners; another 450 arrived the following season. As a result, by 1851, 2,716 Chinese had passed through the Golden Gate. Chinese skepticism about the California gold rush began to dissipate as soon as some of the men returned to China with positive reports of glorious riches to be made on the Western American frontier. No circular could do what personal experience and individual success could.4

Distance did not deter the Chinese from embarking for North America. Since the 1780s, a handful of Chinese sailors, artisans, and traders had visited the West Coast and Hawaii. In the mid–nineteenth century, a voyage by a sailing vessel between Hong Kong and San Francisco usually took forty-five to sixty days. After 1867, steamships shortened the traveling time to thirty days, roughly the same time it took for a stagecoach to roll from Missouri to California. However, a stagecoach ride cost at least $500, compared with $40 to $50 for this transpacific journey. To most people on the East Coast, driving a wagon west seemed more realistic, even though it took about six months to cross the continent. The voyage around South America also took about half a year. As a consequence, the Chinese in coastal regions could get to the gold fields much more quickly than most Americans and all Europeans.5

The greatest impetus for large-scale Chinese immigration to America, however, came from the tumultuous Chinese society itself. In the nineteenth century, the Chinese empire faced a series of unprecedented problems that threatened its very survival. As the result of the Columbian Exchange, new crops from the Americas, such as corn, sweet potatoes, and peanuts, brought steady food and energy supplies to the kingdom. Consequently the Chinese population exploded from 150 million in 1600 to 300 million in 1800 to 430 million in 1850. The southern provinces in particular became extremely overpopulated. For example, the ratio of land to population in Guangdong Province, where most Chinese immigrants came from, was 1.67 mu 亩 (less than a quarter of an acre) per person. The government struggled to provide administration and services for such an enormous population. Along with the demographic crisis, foreign military and economic intervention fundamentally weakened China’s traditional economic order and social fabric. A quarter century after the First Opium War (1839–1842), Western countries, through an “unfair treaty” system, forced China to open more ports for trade and to adopt Western business practices. Protected by special rights, foreign merchants and companies gradually reduced Chinese tradesmen to a subordinate role. New trade routes, commodities, and methods affected the livelihood of people in many parts of the country. Forced by Western powers, the opium trade drained a large amount of silver from China and drove up the price of silver at a shocking rate. Since silver was the standard for payment of taxes, this situation put a tremendous economic burden on the peasants. Yet the greatest danger to ordinary citizens during this period was a number of rebellions across the country. These conflicts’ pervasiveness and duration caused an unimaginable degree of destruction. Nearly toppling the Qing dynasty, the Taiping Rebellion, the bloodiest of them all, ravaged the entire South from 1851 to 1864. In a little more than two decades, more than 20 million people lost their lives in these rebellions. The whole of China was in disarray.6

The hardship wrought by this violent period motivated a massive outmigration, especially from the South. Located in the southern tip of China, Guangdong Province alone supplied more than 90 percent of the California-bound gold seekers. For centuries, citizens of Guangdong had enjoyed prosperity, often eluding famines and other disasters common in other parts of the vast country. The only legal trading port until 1842 in China, Canton (Guangzhou), the capital of the wealthiest province, also served as the nation’s commercial center. The First Opium War, however, changed everything. In the war, the British Navy inflicted the first major military defeat upon Chinese forces near Canton, which was entirely at the mercy of the intruders’ field guns. The Treaty of Nanjing (1842) forced the Chinese government to open four more ports for trade. As a result, Canton lost its monopoly on trade. One of the new international ports, Shanghai, which enticed much of the transpacific commerce, began to rival Canton for economic supremacy. Politically, the conflict also weakened Chinese authority in the region, and bandits and gangs freely roamed, preying on defenseless peasants. Ten years of social disorder eventually precipitated the Taiping Rebellion in neighboring Guangxi Province. Although the Taiping troops were never able to enter Canton, they left a swath of destruction through the countryside. An epidemic caused by decomposing bodies added more horror to the misery. Even two years after the end of the rebellion, conditions were still horrible.7 It was reported in the North-China Herald that the “fields are all thickly overgrown with grass, human bones are lying about everywhere, the houses are open and empty, but human skeletons are lying on the beds.”8 By the early 1850s, those devastating conditions inspired a massive exodus from the South of China.

For many unfortunate and desperate Cantonese, 1852 became the year of decision. The outbreak of the Taiping Rebellion made practically anywhere more appealing than the devastated homeland. Neither Cuba’s sugar plantations nor Peru’s guano pits scared people anymore. For over a century, the Cantonese had been venturing into Southeast Asia from Borneo to Malaya. California offered just another choice on a long list of destinations. The San Francisco customs house reported a sudden surge of Chinese passengers, a total of 20,026 in 1852, passing through the Golden Gate. It was the highest number of Chinese to enter the port in a single year in the first three decades of Chinese immigration into the United States. After this initial wave, the stream of Chinese newcomers leveled off. An average of 10,000 came annually between 1852 and 1882. During that period, the U.S. government recorded the entry of some 340,000 Chinese, equal in 1880 to the entire population of New Hampshire and twice the population of Oregon. The actual number of Chinese immigrants was probably higher than these official figures. This substantial influx of Chinese would have made a distinct impact on any region, even one as vast as the trans-Mississippi West.9

Although most of these Chinese missed the initial gold rush, few failed to strike real fortunes. Gold production in California did not reach its peak until 1852, with a total of $81 million in output, compared with $10 million for 1849. Prospectors often anticipated bigger and better finds. After taking out the “easy” gold, Anglo miners either sold or abandoned “exhausted” claims and moved on to new diggings. The Chinese gobbled up these deserted claims at little or no cost. Their cooperative strategies, extraordinary patience, low expenditure, and superb water management allowed them to thrive throughout the gold fields. In a few years, Chinese possessed most of the claims in the area of the American River and its tributaries, and they constituted the single largest national group of miners. In 1860, 30 percent of the miners were Chinese. A decade later, they made up 57 percent, or 17,363 of 30,330 of California’s miners. As a contemporary U.S. government report stated, “Since most of the Chinese in the United States are engaged in placer mining on their own account, it is evident that they are well adapted for success in that branch.”10 From 1855 to 1870, the Port of San Francisco alone recorded shipments of $72,581,219 in gold and silver to China. With a distinctive pattern of starting slowly, then quickly dominating placer mining, the Chinese in the next quarter century repeated their successes throughout the mining West.11

Contrary to Frederick Jackson Turner’s poetic metaphor of westward expansion, the Chinese American and mining frontiers extended eastward. Branching out from northern California, the Chinese steadily spread to almost every corner of the West. Their extensive placer operations reached Nevada, Oregon, and Washington in the 1850s; Idaho and Montana in the 1860s; and Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, and Dakota in the 1870s. At that time, the Chinese constituted more than 25 percent of all miners in the West. This disproportionate representation of Chinese in the industry gave some Western mining states and territories a prominent Chinese population. In 1870, Chinese constituted 7.4 percent of Nevada’s population; 8.8 percent of California’s; 9.5 percent of Montana’s; and an astonishing 28.5 percent of Idaho’s, with 4,274 of 14,999 residents. Mineral extraction often brought instant wealth to both individuals and communities. Because Western mining offered the Chinese great economic opportunities, they contributed to the quick settlement of the West by building hundreds of towns and camps, many in remote areas across the region.12

Like the frenetic mining rushes, the construction of the transcontinental railroad, another national mania, lured Chinese from the mid-1860s to the mid-1880s into the interior American West. In 1862, Congress authorized the construction of the first transcontinental railroad. The Central Pacific would move from Sacramento eastward to meet the Union Pacific from Omaha, linking the West Coast to the East. Yet, while the Union Pacific enjoyed a stable labor supply of Irish immigrants, the Central Pacific constantly struggled to keep a committed crew. Higher wages in mining and elsewhere in California made railroad jobs unattractive. The company first toyed with the idea of bringing in Confederate prisoners or perhaps freed blacks from the South. In 1865, Edward B. Crocker, former chief justice of the Supreme Court of California and current legal counsel to the Central Pacific Railroad, suggested hiring Chinese men, who had earned a reputation as excellent workers in the mining industry. All doubts about their physical strength, skill levels, and day-to-day reliability were gone soon after the Central Pacific put fifty Chinese to work on railroad construction. Impressed with their performance, the company began to recruit the coveted workers from San Francisco to Hong Kong. Dwindling gold production and increasing ethnic violence forced many Chinese to take the low-paying railroad jobs. The employment offered by the construction of the transcontinental railroad served as a “safety valve” that released pressure from California’s job market.13

The benefits for both Chinese job seekers and the railroad company proved to be enormous. The Central Pacific agreed to pay each employee $30 in gold coin per month for working six days a week. Taking out living expenses, a railroad worker could save $20 a month, about a year’s wage in China. In 1866, 11,000 Chinese were working in the High Sierra for guaranteed gold coins. A San Francisco–based Chinese newspaper, China Mail and Flying Dragon, called in 1867 for another 3,000 workers. The Pacific Mail Steamship Company sent extra steam lines to Hong Kong to pick up the potential workers. Collis Huntington, the chief financial officer for the railroad, hoped many more would make the voyage when he wrote, “It would be all the better for us and the state if there should a half million come over in 1868.” Eventually Chinese made up more than 90 percent of the railroad company’s labor force, which on May 10, 1869, finished the first transcontinental line in the United States at Promontory, Utah. The success of the Central Pacific motivated other railroad companies to recruit the highly productive Chinese workers. In the next two decades, all of the Western railroad giants, including the Southern Pacific and the Northern Pacific, employed large numbers of the Asians. The latter company at one point employed 15,000 Chinese on lines throughout Washington, Idaho, and Montana. Some Southern railroads also utilized Chinese laborers. Even after completion of the railroad network, the companies kept many Chinese on maintenance crews posted at numerous fueling stations and towns, usually set fifty to seventy-five miles apart. Indeed, a Western railroad map could provide a clear picture of the Chinese presence.14

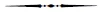

Chinese miners were working at a sluice box near Alder Gulch, Montana, around 1870. (Courtesy of the Montana State Historical Society)

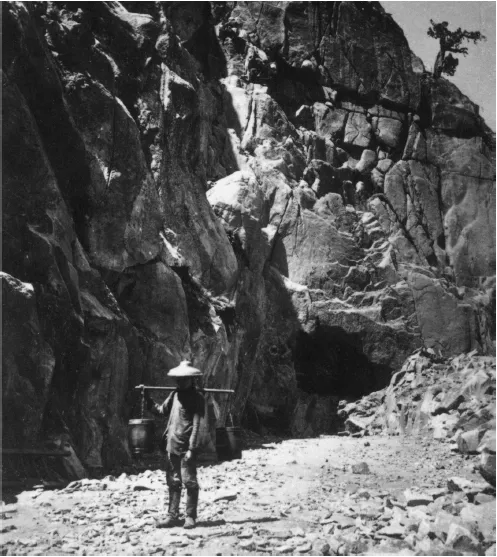

A Chinese laborer working for the Central Pacific Railroad stood in front of tunnel no. 8 in the Sierra Nevada, ca. 1860s. (Courtesy of the Huntington Library)

In addition to their omnipresence in a vast geographical area, Chinese immigrants quickly penetrated into the American economic structure, vigorously competing for jobs in the Western market. In the first decade of their immigration, mining was the predominant calling for the Chinese. Starting in the mid-1860s, they steadily expanded th...