![]()

PART I

Special Chapter

Green Urbanization in Asia

From 1980 to 2010, Asia added more than 1 billion people to its cities.1 More than half of the world’s megacities (cities with 10 million or more people) are now in Asia. Another 1.1 billion people will be added to Asia’s urban population in the next 30 years (UN 2012). From 1980 to 2040, every year more than half of the increase in the world’s urban population has been or will be in Asia. Such a scale of urbanization2 is unprecedented in human history. With all its potential benefits and costs, Asia’s urbanization presents both challenges and opportunities for the region and the world as a whole.

The phenomenal urbanization in Asia is largely driven by fast economic growth, particularly in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and more recently in India. Asia’s growth is dominated (as has happened elsewhere) by the expansion of services and manufacturing. Agriculture experiences a relative decline because the expenditure share on farming products typically drops as income rises and agricultural supply is constrained by the balance between productivity (yield) increases and land conversion to nonagricultural uses. Meanwhile, industrial and service supplies are much less constrained by land as a factor of production and benefit relatively more from deepening physical and human capital stocks. Also, the demand for manufactured products and services is nearly insatiable, as demonstrated by the frequent releases and popularity of new versions of electronic products such as “smart phones” and “tablets.” Because industrial and service production and consumption usually take place in cities, they generate jobs and provide opportunities and attractions for people in general and migrants in particular, leading to continued urbanization.

Urbanization comes with both benefits and costs. “Localization economies” result from agglomerations of firms in the same industry benefiting from spillovers of knowledge and technology, pooling of labor markets, and intensified competition. “Urbanization economies” refers to externalities attributable to agglomerations of firms in the same cities but from different industries, which are taking advantage of backward or forward linkages, reduced transaction costs, and sharing of common services and intermediate inputs. In particular, by locating ambitious, talented individuals in close physical proximity, urbanization helps promote innovation and technological progress, leading to higher productivity. These benefits of urbanization help raise household incomes and firm profitability. It is generally accepted that city growth has made urbanites happier, healthier, and smarter, and cities that can attract and retain skilled people have a bright future (Glaeser 2011, Moretti 2004a).

Urbanization also comes with costs. Noise and congestion are among the most apparent features of cities. City living entails higher costs for housing, raising children, and health care. In addition, income inequality and crime rates tend to be higher in urban areas. The quality of the urban environment receives considerable attention, partly arising from concerns over the sustainability of development and climate change, and partly from shifting preferences as incomes rise.

Asia has already been facing enormous environmental challenges. Three of the top five carbon dioxide (CO2) emitting economies and 11 of the 20 most polluted cities in the world are in Asia. In many Asian nations, losses from traffic-related congestion amount to 5% of gross domestic product (GDP) (ADB 2012a). In rich Asian cities (such as Hong Kong, China; Singapore; Seoul; and Tokyo), high incomes and technology that became available during the last 50 years have already resulted in much pollution and a large ecological footprint. The situation is particularly worrisome in poor cities that experience rapid growth, where pollution is becoming extremely serious, infrastructure supply lags behind demand, and basic public services such as water connections and solid waste disposal do not reach the majority. In addition, many residents live on marginal lands where they face risks from flooding, disease, and other shocks.

In the absence of appropriate interventions, urbanization and further economic growth may result in greater deterioration of the environment and urban living conditions. For example, the region was home to 506 million slum dwellers in 2010, more than 61% of the world’s total.

This special chapter focuses on the environmental challenges Asia faces as it urbanizes. It begins by highlighting special features of Asia’s urbanization in the next section, including its massive scale and low level, the fast pace of urbanization, high population density, and more and growing megacities.

The chapter then discusses the environmental challenges associated with urbanization, covering topics of urban air pollution, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, access to water and sanitation, loss of natural ecosystems and amenities, and urban slums and poverty. Given the increasing concerns about sea level rise associated with climate change and the number of coastal cities in Asia, estimates of population at risk due to coastal flooding and the proportion of city population affected by this risk are presented. But the future does not need to be grim.

Thus, the chapter presents arguments to support a cautiously optimistic and achievable environmental prospect for Asia as it continues to urbanize. While “business as usual” could make things worse, certain forces and mechanisms associated with urbanization if managed properly can help counter the trend in environmental degradation. These forces include declining fertility, rising educational levels, relocation of manufacturing away from city centers, innovations in green technology, and improvements in urban infrastructure. The environment -urbanization relationship (using air particulate matter pollution and CO2 emission as indicators) will be investigated and used to depict a possible green urbanization path for Asia.3

A green urbanization path, of course, is not automatically achievable unless appropriate policies and interventions are designed and implemented in a timely fashion. Before concluding, the chapter offers a number of evidence-based policy options that can help achieve a win-win scenario of urban growth with improvement in the environment.

Special Features of Urban Growth in Asia

In a process similar to that much earlier in Europe, Latin America, and Northern America, Asia has been urbanizing for many years now and the process is projected to gain momentum in the coming decades. Unlike other regions, however, Asia’s urbanization is different in several key aspects.

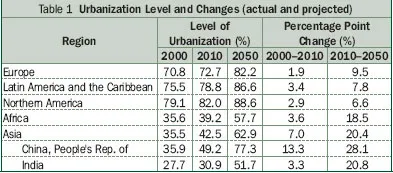

First, urbanization in Asia has been occurring rapidly and will continue to do so in the foreseeable future. Table 1, which is based on data and projections of the UN (2012), tabulates the level of urbanization and its change for different regions and two Asian economies. The last two columns of Table 1 show the total percentage point increase in the level of urbanization for the periods 2000–2010 and 2010–2050. While Asia increased its urbanization level by 7 percentage points in 2000–2010, Africa—the second fastest urbanizing region during the same period—only experienced a 3.6 percentage points increase. Similarly, during 2010–2050, Asia is projected to increase its urbanization level by 20.4 percentage points, but the projected increase for Africa is only a total of 18.5 percentage points.

Source: ADB estimates based on UN (2012).

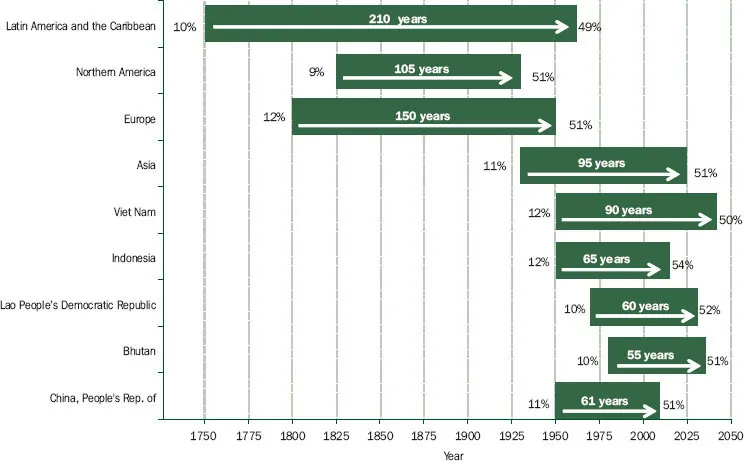

More revealing is a comparison of the number of years between the start of a region’s urbanization, when about 10% of its population was urban, to when about 50% of its population is urban. Figure 1 shows that this process lasted 210 years in Latin America and the Caribbean (from 10% in 1750 to 49.3% in 1960), 150 years in Europe (from 12% in 1800 to 51.3% in 1950), and 105 years in Northern America (from 9% in 1825 to 51% in 1930), and it will take 95 years or less in Asia (from 11% in 1930 to 51% in 2025). For countries within Asia, this process lasted only 61 years for the PRC and is estimated to last 55 years for Bhutan, 60 years for the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), 65 years for Indonesia, and 90 years for Viet Nam.

Figure 1 Number of Years from about 10% to 50% Urbanization

Note: Extrapolation and interpolation were used to estimate urbanization level and corresponding starting years for Latin America and the Caribbean and Northern America.

Sources: ADB estimates based on Bairoch (1988) and UN (2012).

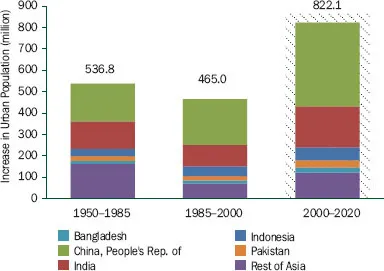

Second, the absolute increase in city population in Asia is unprecedented, partly due to its large population base and partly due to its fast speed of urbanization. Since the 1950s, Asia has added more than 1.4 billion people to its cities (Figure 2). Almost 537 million were added during the 35 year interval of 1950 to 1985. But in the following 15 years, 1985–2000, 465 million were added. More strikingly, from 2000–2020, a total of 822 million will be added. Figure 2 also provides geographic breakdowns of these numbers. Clearly, most of these increases are from Bangladesh, the PRC, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan, Asia’s most populous countries.

Figure 2 Increase in Urban Population in Asia (millions)

Note: Data for 2010-2020 are based on projections of UN World Urbanization Prospects, 2011 Revision.

Source: ADB estimates based on UN (2012).

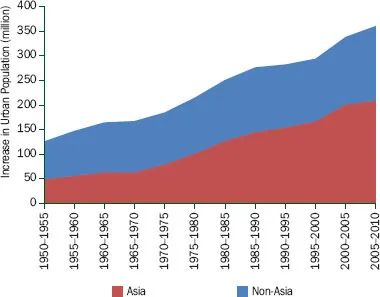

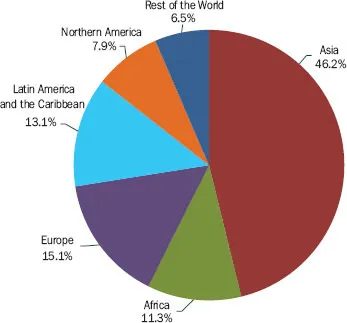

To some extent, global urbanization is largely an Asian phenomenon (Figure 3). Since the early 1980s, Asia has added more people to the global urban population than all other regions combined. By the latest available statistics, Asia is now home to almost half of the total urbanites on earth (Figure 4)—Asia’s urban population is more than three times that of Europe, the second largest region in terms of urban population (UN 2012).

Figure 3 Increase in Urban Population, 1950–2010

Source: ADB estimates based on UN (2012).

Figure 4 Regional Shares of Global Urban Population, 2010 (%)

Northern America = Canada and the United States.

Source: ADB estimates based on UN (2012).

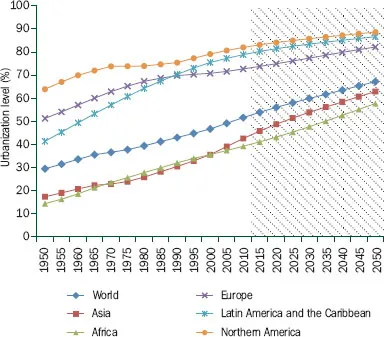

Third, contrary to the unprecedented expansion of city population, Asia’s level of urbanization is still low. As shown in Figure 5, the level of Asia’s urbanization (i.e., the share of its population living in urban areas) has been lower than that of the world at least since 1950. Across regions, Asia was the least urbanized, even less than Africa, during 1970–2000. In 1960, only 20.7% of Asia’s population was urbanized versus 33.6% for the world. In 2000, 46.7% of the world’s population lived in cities while only 35.5% of the population in Asia did so. In 2010, these urbanization shares moved to 52% and 43%, respectively. Thus, the urbanization gap between Asia and the rest of the world has narrowed but remains large.

Figure 5 Level of Urbanization by Region (%)

Northern America = Canada and the United States.

Source: UN (2012).

The gap in the urbanization level between Asia and the world will narrow further (UN 2012). By 2050, while 62.9% of Asians will live in cities...