![]()

1 Introduction

Thailand depends heavily on natural gas and imported oil. Significant subsidies on fossil fuels and electricity—which in turn require subsidies on fuel for power generation to keep state-owned utilities financially viable—are a heavy burden on public finances. As such, energy price reforms are being implemented in the country. As rising oil prices from the mid-2000s amid fuel subsidies threatened fiscal stability, the government capped diesel prices in mid-2008 to alleviate the impact of the rising prices. It reintroduced diesel subsidies in December 2010, committing to maintain diesel prices at around B30 per liter.

Recognizing the country’s overreliance on gas and oil, Thai policy makers have made a distinct move to promote alternative energy sources. Indeed, Thailand got early into the renewable energy space among the ASEAN-5 economies.1 In the wider region, Thailand has arguably achieved the most success in gas and electricity tariff reform, contributing to a steady flow of investment, which should provide some fiscal space. But it has had limited success removing oil subsidies, although sharply lower global oil prices in 2015 have eased the subsidy burden and helped the country recoup some of the costs incurred in years when they were high. It remains to be seen if Thailand will secure these gains and take steps to prevent subsidies from returning once world oil prices rise again.

Fossil fuel subsidies are a prominent feature of many Asian economies, including Thailand. These are categorized either as consumer subsidies—benefiting users such as transport and manufacturing industries and electricity generation—and producer subsidies, which lower costs for producers involved in the exploration, extraction, or processing of energy products. Subsidies contribute to fiscal imbalances in many countries and operating losses in utilities, in addition to other unintended negative consequences. They restrict public expenditure on development priorities such as education, health, and infrastructure; are inefficient for supporting low-income households; and encourage excessive consumption through low energy prices, increasing air pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. The need to reform fossil fuel subsidies has increasingly been recognized, with international and national commitments to phase out inefficient subsidies.

The objective of this study is to systematically assess the prevalence of different types of fossil fuel subsidies in Thailand and analyze the potential impacts of their removal. It is hoped that this will provide detailed inputs for the ongoing efforts to reform the subsidies.

The following section provides an overview of the energy sector in Thailand. Section 3 presents new, estimates of fossil fuel subsidies. These go beyond the standard method of calculating the gap between a reference or cost price and final consumer price to an approach that allows quantification of a subsidy at different stages of price formation from primary resources to final consumption. Section 3 also presents the economic, energy, and environmental impacts of reforming fossil fuel subsidies. Section 4 discusses the need for shielding the poor against the potential rise in energy prices, and Section 5 presents a summary of the findings.

![]()

2 Overview of the Energy Sector

The 15-year Renewable Energy Development Plan launched in 2008 encouraged the use of renewable energy. Since then, Thailand’s energy policy has sought mainly to maintain energy prices; intensify energy development, including alternative energies to achieve and secure adequate energy supply; push for energy efficiency and preservation in the household, industry, and transportation sectors; and encourage environmentally friendly energy procurement and consumption. Policy changes in Thailand’s energy diversification strategy are designed to have an impact on the energy mix, leaning toward coal and renewables. By 2030, it aims to increase coal to 36 million tons of oil equivalent of primary energy and stabilize gas consumption.

Resources and Market Structure

Of Thailand’s domestic energy resources—coal, crude oil, and natural gas—the latter is most abundant, supplying about 70% of the country’s natural gas needs (PTT 2012). Domestically produced coal is mostly lignite, used primarily for electricity generation. Coal is also imported for use by electricity generators and industry. About 20% of crude-oil needs are produced domestically. Oil is refined domestically and Thailand is a net exporter of petroleum products (Energy Policy and Planning Office 2013a). The country’s oil and natural gas reserves are limited, however. The estimated reserves-to-production ratio is 3.5 years for oil and 12.5 years for natural gas. Lignite reserves are larger, with a ratio of 100 years (BP 2012).2 Thailand is increasingly relying on natural gas to generate electricity, with natural-gas-fired electricity in 2014 accounting for about two-thirds of total electricity generated by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT; the state electricity generator and market operator), far ahead of coal/lignite, at about one-fifth (Energy Policy and Planning Office 2013b).

As a net energy importer, over 60% of Thailand’s energy consumption comes from imports. Discovery of oil and gas is an ongoing process, but domestic demand for energy has also grown, leaving little overall change in import dependency (Asian Institute of Technology 2010). Alongside the surge in world oil prices during the past decade, this increase in consumption pushed the cost of net energy imports to 1.2 trillion Thai baht (B) in 2011 or 11% of gross domestic product (GDP) (Energy Policy and Planning Office n.d.).3

Natural gas is the most widely consumed fuel in Thailand, at 45% of total commercial energy consumption (primarily for electricity generation), followed by petroleum products (36%), coal (12%), lignite (5%), and hydroelectricity (3%) (Energy Policy and Planning Office 2013a). Biofuels and solid biomass are also important components.4 Electrification is high, at 100% in urban and 99% in rural areas.

Thailand’s energy industry has both public and private sector entities. The government owns 66.4% of the national oil and gas company, PTT Public Company (PTT), with a 51.1% outright stake and 15.3% through the government-supported equity fund Vayupak (Standard and Poor’s Rating Services 2013). PTT produces the majority of domestically produced oil. The oil sector is open to foreign involvement, although foreign companies often work in joint ventures with PTT. The company, likewise, has a stake in some natural gas production, although foreign companies dominate (US Energy Information Administration 2013). PTT has a monopoly on natural gas distribution. Electricity is largely produced by the 100% government-owned EGAT, which also has a monopoly on electricity distribution. Independent power producers are involved in generation. The Energy Policy and Planning Office (within the Ministry of Energy) oversees all aspects of energy policies, including the oil, natural gas, and power sectors.

Prices, Taxes, and Support Mechanisms

Thailand subsidizes consumption of petroleum and natural gas products through the Oil Stabilization Fund (an oil price fund), tax exemptions, and caps on ex-refinery and retail prices. It caps retail prices for diesel, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and natural gas for vehicles (NGV),5 and subsidizes biofuel blends. For diesel and NGV, price subsidies are universal in that wealthy and poor consumers alike can access them. LPG prices vary depending on the consuming sector, and electricity prices are subsidized for low-consuming households.

The oil fund is a monetary reserve that acts as a means of reducing price volatility and for cross-subsidization (Box 1). Levies are imposed on fuels. Subsidies may be provided on a per-liter basis or as lump sum to fuel producers or distributors. Over the years, the oil fund has been used to (i) reduce price spikes; (ii) cross-subsidize fuels for economic, political, or social reasons; and (iii) encourage greater use of domestically produced energy resources. Gasoline, kerosene, and fuel oil are the petroleum products that most often face oil fund levies. The fuels most often subsidized are higher biofuel blends and LPG. Oil fund levies and subsidies are adjusted weekly, and it is not unusual for a levy to be applied one week and a subsidy the next to keep retail prices stable. This is particularly true of automotive diesel, which the government has committed to maintain at about B30 per liter since late 2010. In theory, the oil fund is revenue neutral. In practice it has required injections of government funds during periods of prolonged deficits (most recently in 2004) and borrowings from commercial banks to allow ongoing deficits (most recently in 2012) (Leangcharoen, Thampanishvong, and Laan 2013).

Box 1: The Oil Fund in Action: High-Speed Diesel

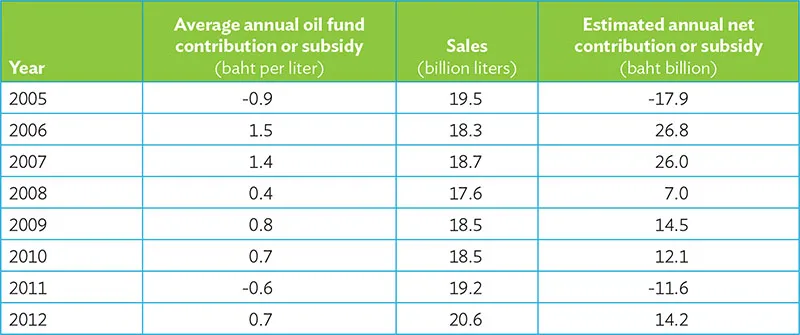

Between 2005 and 2012, net oil-fund levies were applied to diesel in all but 2 years. Based on annual average levies and total diesel consumption, diesel made a net contribution to the fund over this period (Table B1). The oil fund has, therefore, played a stabilizing role in diesel prices and was not considered a subsidy for this fuel (diesel did receive a significant tax reduction, however).

Table B1: Estimated Flows of Funds to and from the Oil Fund for High-Speed Diesel*

Note: Positive figures in the table indicate instances where the levy is being applied and high-speed diesel sales have raised revenue for the oil fund. Negative figures indicate years in which a subsidy for high-speed diesel has been provided and this has drawn on oil fund revenues.

* Based on average annual levies or subsidies.

Sources: Calculations based on data from the Energy Policy and Planning Office (2013c) and Energy Fund Administration Institute (2013).

The LPG pricing mechanism is complex. The ex-refinery price has been capped at $333 per ton since 2009, significantly lower than the world price. Retail prices are also capped for all sectors except the petrochemicals industry. Oil-fund levies are applied to the cooking, transport sector, and industry sectors. Lump-sum transfers are made from the oil...