eBook - ePub

Effectiveness of Central Banks and Their Role in the Global Financial Crisis

Case of Selected Economies

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Effectiveness of Central Banks and Their Role in the Global Financial Crisis

Case of Selected Economies

About this book

This study examines the role and performance of central banks in low-income countries that have faced a range of domestic and external fragilities, aggravated by the global financial crisis that started in the United States and other advanced economies. It focuses on a select group of developing member countries of the Asian Development Bank in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and South Asia that have been and will continue to be vulnerable to adverse external developments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Effectiveness of Central Banks and Their Role in the Global Financial Crisis by Shamshad Akhtar, Henri Lorie, Arne Petersend in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Banks & Banking. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Regional Comparative Analysis

The Macroeconomic Context

In the 5 years leading to the global financial crisis, the selected developing member countries (DMCs) benefitted to varying degrees from a favorable external environment and a strengthening of macroeconomic management, as well as from continued structural reforms. Among the countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia, Armenia and Georgia stand out in terms of progress with market-oriented reforms and macroeconomic management, although the Kyrgyz Republic also pursued coherent macroeconomic policies. As a result, growth rates in the 5 years leading to the 2008 global crisis were especially high in this group of countries, averaging more than 10% annually in Armenia and Georgia. Growth was also in the double digits in Afghanistan, reflecting the reconstruction effort in that country. Inflation in the strong economic performers was mostly under control, at least until the surge in international commodity prices, but evidence of domestic overheating was emerging during 2007–2008. Although the external current account deficit was often large, capital inflows were sufficiently strong and helped finance these deficits, while allowing for an increase in international reserves. In South Asia, progress with structural reforms, starting from a higher base, was probably less, but in Nepal, the exceptionally fast development of the finance sector is notable. Growth was steady but relatively weak in Nepal as activity in the export sectors was under strong pressure from external competition. There was little progress with fiscal consolidation in Sri Lanka, but buoyant private sector activity helped maintain a fairly high rate of economic growth of about 7% annually.

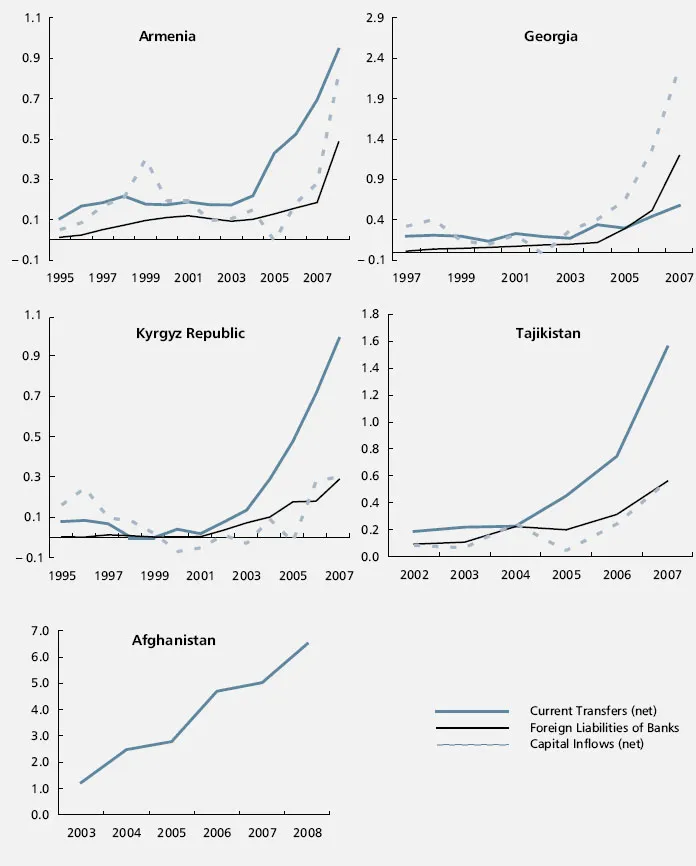

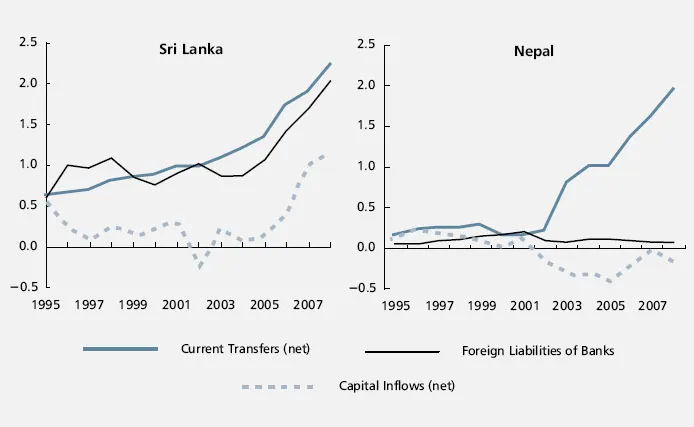

A key factor underpinning the growth in domestic demand was surging workers’ remittances and capital inflows, in various degrees (Figures 1a and 1b). In the Caucasus and Central Asia, the origin of remittances has mostly been the Russian Federation and, to a much lesser extent, Kazakhstan. In South Asia, remittances were mostly from India and the Gulf countries.2 Remittances reached 50% of gross domestic product (GDP) in Tajikistan, 20% in the Kyrgyz Republic, and about 10% in Armenia. In Nepal, remittances reached 19% of GDP, and in Sri Lanka, 6%. Foreign workers from Nepal are mostly employed in the construction sector. Besides remittances, there was a surge in private capital inflows, especially in Georgia (where it reached 20% of GDP in 2007), Armenia, and the Kyrgyz Republic. In the latter case, capital inflows were mostly reflected in drawings by Kazakh banks located in the Kyrgyz Republic on credit facilities from their head offices. Inflows of official transfers were particularly high in Afghanistan in support of its reconstruction efforts. In Sri Lanka, the rise in private capital inflows mainly coincided with direct and portfolio investment as well as external borrowing by banks.

Figure 1a: Current Transfers and Capital Inflows

($ billion)

Source: International Monetary Fund: International Financial Statistics.

Figure 1b: Current Transfers and Capital Inflows

($ billion)

Source: International Monetary Fund: International Financial Statistics.

The global financial crisis has generated severe shocks impacting the selected DMCs— as evident from the trends in private capital inflows that have suddenly stopped and reversed, and the remittances that have sharply declined. Afghanistan and Nepal appear to be exceptions so far. In Sri Lanka, while net capital inflows have reversed, remittances have remained strong, although declining somewhat in early 2009. In part, this may reflect differences in the timing and intensity of the global financial crisis in originating countries. The correction in international commodity prices, particularly oil, has generally provided some relief to balance of payments and inflation in most oil importing countries. But in many cases, their exports are being threatened as well by the global recession (e.g., textiles in Nepal and Sri Lanka, and wines in Georgia). Several countries have also been adversely affected by the decline in some specific commodity prices (e.g., diamond and mineral products in Armenia, and aluminum and cotton in Tajikistan). As a result, while imports decelerated fairly automatically with the slowdown or decline in remittances and, to some extent, the lesser availability of foreign financing, the overall external current account positions might not improve without adjustment policies. On the financing side, the reduced amount of foreign capital that might be available will certainly be on more expensive terms, as the global financial crisis has sharply reduced the appetite for risk, as shown by the surging spreads and credit default swap (CDS) rates for both official and private debts.

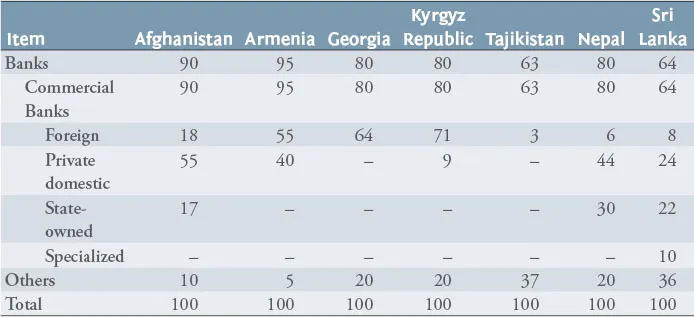

Development of Finance Sectors

The finance sector, which has been dominated by banks, has grown significantly in most selected countries in recent years. The growth was perhaps most impressive in the Kyrgyz Republic and Nepal, while it was more modest in Sri Lanka, which has started from a higher base. Banks have dominated the finance sector, largely because of underdeveloped financial markets. They have been in a better position to address the severe asymmetric information problems that characterize financial intermediation in most developing and emerging countries, particularly in the former Soviet Union. The assets of banks account for anywhere between 65% of total financial assets in Sri Lanka and 95% in Armenia. The ratio of about 65% in Tajikistan entirely reflects the importance of a cotton financing nonbank financial intermediary (Table 1).

Table 1: Selected Developing Member Countries: Structure of the Financial System

(% of total financial assets)

– = not available.

Note: Based on data for 2007 or 2008.

Sources: Central banks, 2007 or 2008 annual reports.

Nevertheless, bank penetration is low despite the large number of banks. Corporate lending remains the main banking activity in most countries. Banks continue to be present mostly in urban centers, except for those in Nepal and Sri Lanka, where penetration in the rural areas appears to be deeper. Sri Lanka has a ratio of about one bank branch per 10,000 people—about three times the level in Tajikistan. Moreover, the banking system in the selected countries remains somewhat fragmented, with the number of banks often above 20, despite the small country size. However, a few banks tend to account for a large share of assets and deposits and concentration is fairly high, giving much room for consolidation. Most banks in the Caucasus and Central Asia are privately owned. Foreign ownership of banks is significant in Armenia, Georgia, and the Kyrgyz Republic (HSBC, in particular). In Nepal and Sri Lanka, state-owned banks still account for a significant share of assets (20%–30%), while foreign ownership is relatively low.

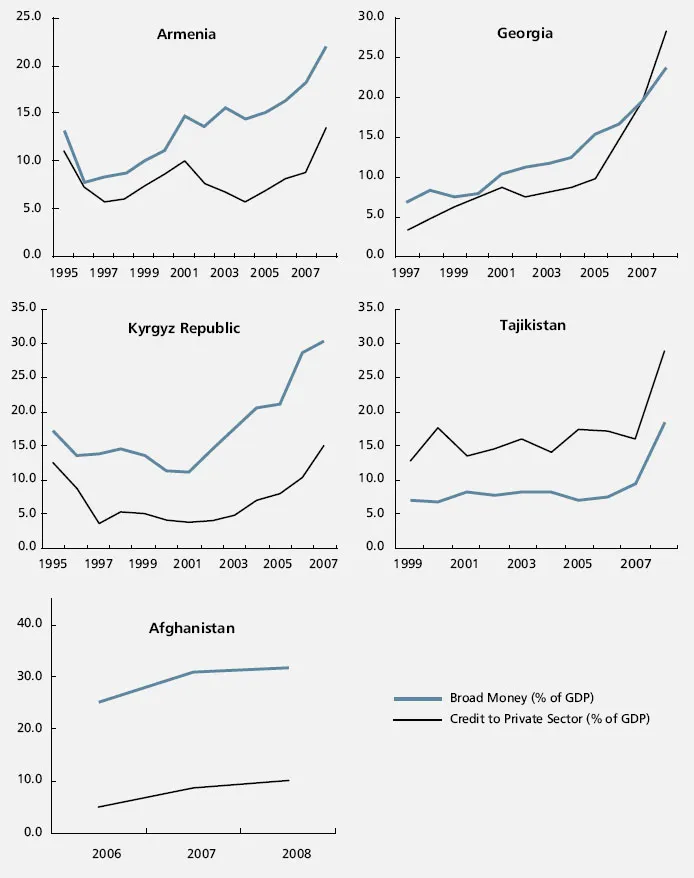

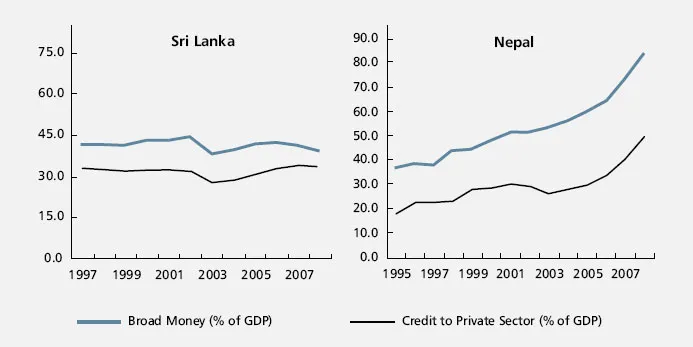

The indexes of financial deepening show, in most cases, some progress in 2003–2008, with both deposits and private sector credit rising significantly, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), although still low by international standards (Figures 2a and 2b). Broad money/GDP ratios now range from a still very low level of 15% of GDP in Tajikistan to 30% in the Kyrgyz Republic. It is about 40% in Sri Lanka and more than 80% in Nepal. Typically, private sector credit/GDP ratios are somewhat below the broad money/GDP ratios, and average less than 20% of GDP in the Caucasus and Central Asia, with that in Afghanistan accounting for 10%. Georgia and Tajikistan are exceptions, with higher private sector credit/GDP ratios that reflect the utilization of some foreign lines of credit by banks. The private sector credit/GDP ratio is just above 30% of GDP in both Nepal and Sri Lanka. This is still only about a third of that in Thailand, and less than those in Egypt and India, although slightly higher than those in Pakistan and Philippines.

Figure 2a: Index es of Financial Deepening

(% of GDP)

GDP = gross domestic product.

Source: International Monetary Fund: International Financial Statistics.

Figure 2b: Indexes of Financial Deepening

(% of GDP)

GDP = gross domestic product.

Source: International Monetary Fund: International Financial Statistics.

Dollarization is still high in the Caucasus and Central Asia countries. After significant improvements in this front in recent years, a wave of re-dollarization has returned, in some cases as local currency came under pressure with the onset of the global financial crisis. Reportedly, 75% of deposits and loans were denominated in foreign currency in Georgia at the end of 2008. Dollarization has also increased in 2008–2009 to 60% in Armenia and 50% in the Kyrgyz Republic. In Sri Lanka, by contrast, foreign currency deposits accounted for only 25% of total deposits in 2008, with little being changed from previous years. Because open foreign exchange positions of banks are strictly limited by prudential regulations, dollarization on the deposits side has tended to be matched by dollarization on the loans side. The financial crisis has also led to some financial disintermediation with the dollar currency in circulation outside the formal sector being quite high, especially in Armenia. In Tajikistan, recent changes in cotton financing (away from foreign sources) has led to a reduction in foreign exchange-denominated claims and deposits.

Dollarization introduces significant vulnerabilities even if open foreign exchange positions are strictly limited. At the bank borrowers’ level, vulnerabilities result if the corporate entities and individuals borrow in foreign currency, while their revenue and income stream is mostly in local currency. This situation creates higher credit risks in an environment of exchange rate instability (depreciation) if the borrowers do not have adequate hedging options as is the case in all selected countries. At the banks’ level, the financial crisis is a reminder that foreign funding cannot be a substitute for domestic resource mobilization, which is key to the sustainability of the banking system. The reliance on foreign funding (as in the case of the Caucasus and Central Asia) can endanger the solvency of some large banks of systemic significance.

While competition has improved in most banking systems in recent years, there is room for further progress. The banking system has improved most in Armenia, Georgia, and Nepal. There is still evidence of weak price competition in Sri Lanka.

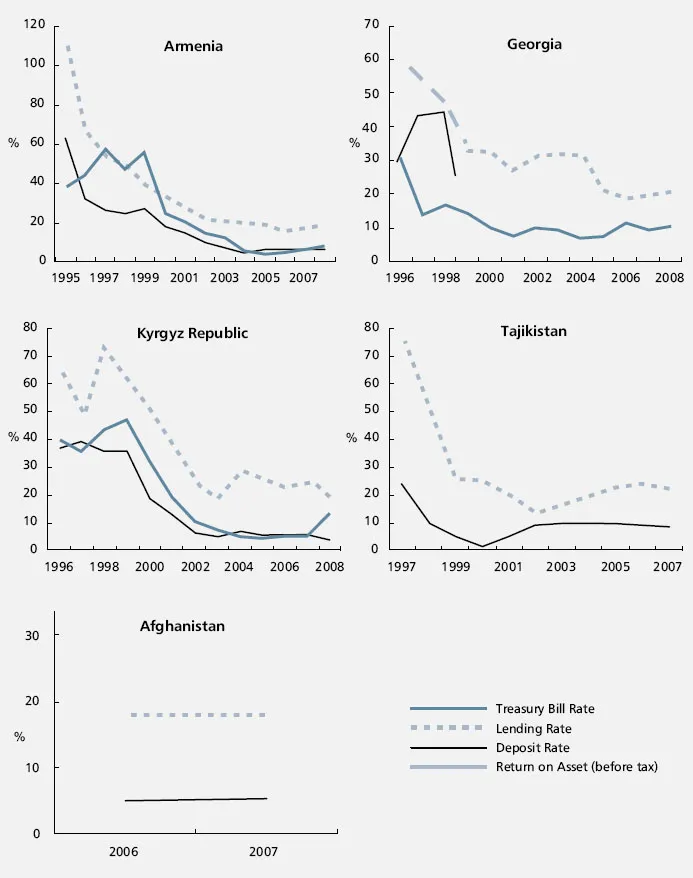

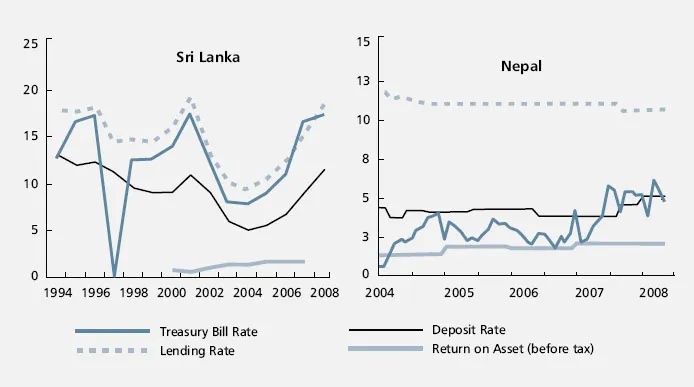

Bank interest spreads have declined where competition has increased, but remain generally large by international standards. The large spreads explain the higher level of profitability (Figures 3a and 3b). The spreads have ranged in 2008 from 6–8 percentage points in Nepal and Sri Lanka to 20 percentage points in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan. In Armenia and Georgia, interest spreads have declined to just above 10 percentage points, compared to the world median of about 6 percentage points. The higher spreads are perhaps not surprising given the high cost of doing business in most selected countries, with Nepal and Sri Lanka perhaps relative exceptions. However, where spreads are high, profitability is also high. The rate of return on assets is as much as 4% in the Kyrgyz Republic, and 3% in Armenia. Not surprisingly, the rate of return on assets has been somewhat lower in Nepal and Sri Lanka, at about 2%, but even this is good by international standards, though less so when compared to the risk-free domestic interest rates.

Figure 3a: Interest Rate Spread

(%)

Source: International Monetary Fund: International Financial Statistics.

Figure 3b: Interest Rate Spread

(%)

Source: International Monetary Fund: International Financial Statistics.

Legal Framework for Central Bank Activities

Objectives, roles and functions, and governance structure significantly affect central banks’ performance of their mandates. The group of seven central banks studied includes a mix of older and newer institutions. In Nepal and Sri Lanka, central banks had to transform themselves from currency boards in the 1950s and have a longer existence, history, and tradition of central bank operations. On the other hand, the central banks of the Caucasus and Central Asia, including those in Armenia, Georgia, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan, have common origins, history, and legal traditions established before and after the breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Upon their creation, the first preoccupation of these central banks was dealing with immediate transition issues, launching domestic currencies, and resolving legacy debt issues. It was only during the mid-1990s that the governments in these countries focused on laying down the legal framework for their central banks and the banking system. The central bank of Afghanistan, after the 2001–2002 conflict, is the youngest and more nascent one. Earlier, it operated on the basis of an outdated 1994 Money and Banking Law. This law primarily positioned the central bank to provide for directed credit to state-owned enterprises. It was not until 2003 that the government adopted a new central bank law and an associated law for the banking sector, which now gives a stronger basis for central banking in a war-torn environment.

The development of central banks in the selected group of countries varies in terms of their historical experience, legal traditions, capacities, and sophistication. This should not be a surprise since some have long traditions while others have not been in existence for long. The countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia had to face the massive challenges of transformation from a centrally planned and closed economy to a marketoriented economy to be integrated within the world economy, and had to assume key roles in liberalizing the banking system and providing a supportive core infrastructure. The dependence of the region on the developments in the Russian Federation made it especially vulnerable to the financial crises in that country.

Irrespective of these differences, all central banks have tran...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Currency Equivalents

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Acknowledgments

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Part I: Regional Comparative Analysis

- Part II: Country Studies

- References

- Back Cover