![]()

1 Introduction

Throughout this study, reference to the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) includes Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam, but not the People’s Republic of China. Clearly, the latter is of a scale and importance requiring stand-alone analysis.

Cambodia, the Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam share common energy security and environmental protection goals. While the Lao PDR and Myanmar have extensive hydropower resources under development, the five countries continue to depend heavily on fossil fuels. Further, firewood and charcoal are still primary energy sources in rural areas throughout the GMS. Both forms of dependence run counter to sustainable and inclusive growth, and the need to reduce greenhouse gases and deforestation. In addition, the growing reliance on energy imports—notably for transportation and industry—makes the GMS countries more vulnerable to external energy supply shocks. Compounding the problem, a doubling or tripling (or more) in energy consumption is expected for these countries over the next 15–20 years. In striving to meet the projected increase in energy demand, the GMS countries will need to do more than simply look for energy additions—domestic or imported. Rather, energy efficiency and conservation are increasingly important.

This publication reviews what is meant by energy efficiency and conservation, particularly on the demand side, and examines related energy efficiency indicators. Alternative assumptions for estimating potential energy savings from improved energy efficiency and conservation are outlined, providing different but comparable views for the five subject GMS countries. Relative to business-as-usual (BAU) conditions, the energy-saving goals and energy efficiency policies of the GMS countries support the conclusion that energy demand could be significantly reduced in these countries over the next 15 to 20 years—possibly by more than 20%.

Following a general review of energy efficiency in the GMS, the institutional and policy frameworks for energy efficiency in each of the five countries are reviewed, and each country’s potential energy efficiency savings are estimated. The volume concludes with a discussion of ways to help ensure that the energy efficiency targets of these GMS countries are met.

![]()

2 Energy Efficiency Defined

Energy efficiency means reducing the energy required for a given level of activity—doing more with less. While improvements in transmission lines reduce electricity losses, better demand-side practices help slow the overall consumption of energy. Energy efficiency measures are often a cost-effective alternative to increasing power supply and energy availability: for example, retrofitting industrial equipment to save a megawatt of power may cost much less than increasing coal-fired generation capacity (ADB 2011b).

A distinction can be made between energy efficiency and energy conservation. Energy efficiency measures, such as optimizing the energy use of computers, printers, photocopiers, and industrial production equipment and machinery, help save energy input while maintaining the same level of output. Switching off lights and appliances when not in use and other energy conservation measures, on the other hand, help reduce the amount of energy used. This publication, however, does not treat energy efficiency and energy conservation measures differently. Both result in energy savings.

Energy efficiency measures taken by many countries have tended to focus on supply-side improvements, in view of the unified ownership or regulation of the supply, transmission, and distribution chain by the public sector. In contrast, efforts to influence the demand side are more challenging, as they must deal with the various considerations that determine how much energy individuals, communities, and industrial users consume. But the importance of demand-side energy efficiency measures is increasingly being recognized, together with the critical influence of electricity tariffs on the effectiveness of such measures. Developing countries typically set electricity tariffs well below full cost recovery, thereby weakening the incentive to conserve energy and to invest in energy efficiency measures.

The following are illustrations of supply-side energy efficiency measures:

• increasing generation efficiency by rehabilitating, replacing, or expanding generation plants; and

• reducing technical losses by rehabilitating, replacing, or expanding transmission lines and networks.

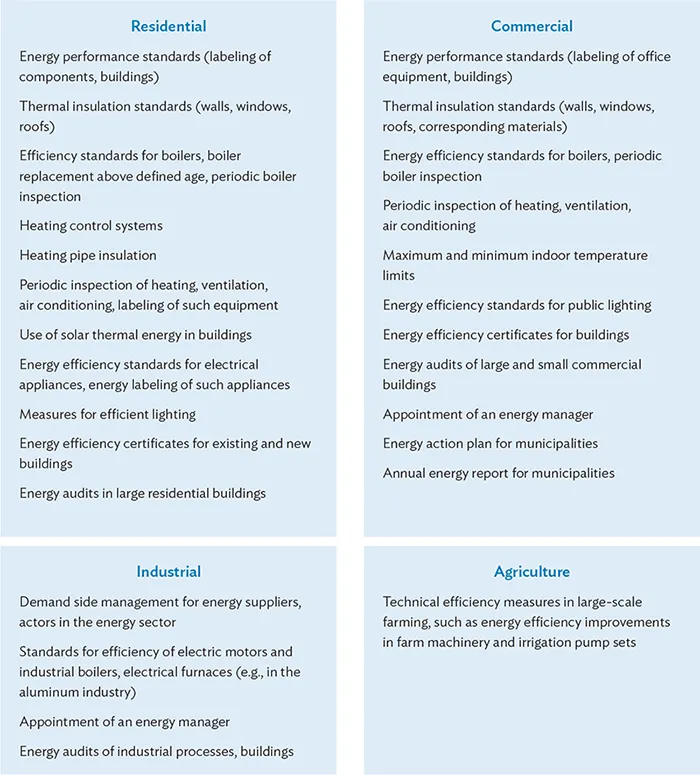

Figure 2.1 lists some demand-side energy efficiency measures. Demand-side economic instruments are just as important, if not more so. In particular, energy prices must reflect the economic cost of supply.

Figure 2.1: Some Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Measures

Sources: UNESCAP (2011); Lahmeyer International.

![]()

3 Energy Efficiency Indicators

Energy efficiency indicators are used to compare energy use by industries or at the national level. Two common indicators are energy intensity and energy elasticity.

Energy intensity is defined as the ratio of energy consumption per unit of output or activity. This indicator serves as a proxy for energy efficiency in intercountry comparisons of energy performance (UNESCAP 2011). Generally, the more intense the activity, the less energy efficient it is. At the macro level, final energy consumption is divided by gross domestic product (GDP) to arrive at energy intensity. If sector or industry data are available, final energy consumption is divided by gross value added to determine energy intensity, or energy used per unit of product.

Energy intensity at the macro level is influenced by objective and semi-objective factors (UNESCAP 2011). Objective factors include geographic and other physical parameters, as well as demographic characteristics. Large or mountainous countries with dispersed populations require more energy for transport than relatively flat, densely populated countries; other things being equal, the first category of countries will have higher energy intensities. Similarly, countries with cold climates require more energy than countries with warm climates. Semi-objective factors include the structure of the economy and the level of industrial development and per capita income.

Sector shifts influence the energy intensity of a country. Industrialization results in a shift from agriculture to energy-intensive manufacturing, whereas highly developed countries tend to shift to services. When energy intensity is used as a proxy for energy efficiency, international comparisons need to correct for differences in economic structure. The challenge is to identify measures that will help decouple economic growth from growth of energy consumption.

Energy elasticity as an indicator of energy efficiency relates the change in GDP following a change in energy consumption. To calculate it, average annual GDP growth is divided by the average annual growth in energy consumption.

Energy elasticity > 1 = more energy-intense economy

Energy elasticity < 1 = less energy-intense economy

![]()

4 Types of Energy Efficiency Potential

The decision to install and use energy-efficient lighting or a myriad other energy-saving appliances is based on factors such as public subsidies and current energy costs. Ultimately, the decision rests on whether the expected energy savings, over the life of the new appliance or equipment, are sufficient to offset the cost of acquiring, installing, and maintaining the appliance or equipment. Electricity tariffs in developing countries often fall far short of their supply costs, thus giving individuals, communities, or industry groups less incentive to adopt energy efficiency measures.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), there are four types of energy efficiency potential: technical, economic, achievable, and program (EPA 2006).

Technical potential relates to possible energy savings through the immediate implementation of all technically feasible efficiency gains, regardless of engineering or nontechnical constraints, including willingness to pay for such measures. Technical potential is not a static concept, as research and technological advances normally strengthen possible energy savings.

Economic potential is a subset of technical efficiency measures that are economically beneficial to the user. For example, the cost of investing in and maintaining and operating new energy savings equipment should be lower than the costs of continuing with current equipment. Awareness-raising and marketing campaigns may be necessary to promote energy efficiency measures. As noted earlier, electricity tariffs set lower than the cost of generation, transmission, and distribution may adversely affect the economic potential.

Achievable potential represents the demand-side efficiency gains that can be achieved under energy efficiency policies and programs. It may include incentives and subsidies that make a noncost-effective efficiency option cost effective for the user.

Program potential refers to energy savings resulting from the specified program design and funding levels. Program potential may be a subset of achievable potential or similar to it.

![]()

5 Estimation of Energy Efficiency Potential

The assessment of energy efficiency potential involves establishing a BAU baseline against which future savings can be estimated. Projections of energy consumption under the BAU scenario assume no change in present energy efficiency measures or programs. Baseline consumption may be expressed in million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe), either on a national basis or by economic sector. In forecasting future energy consumption, contributing factors must be considered, including increases in population, GDP, per capita income, and rural electrification.

Two regional studies provide baseline energy forecasts for the GMS countries, together with estimates of possible savings from energy efficiency initiatives:

• 3rd ASEAN Energy Outlook (2011), prepared by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Centre for Energy (ACE); the Institute of Energy Economics, Japan (IEEJ); and national Energy Supply and Security Planning in the ASEAN (ESSPA) teams; and

• Analysis of Energy Saving Potential in East Asia Region (2011), prepared by the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) and referred to as “the ERIA study” throughout this publication.

These studies use the same basic methodology and both utilize the IEEJ World Energy Outlook Model. However, there are significant differences between the studies regarding past and future energy consumption levels,1 as well as assumptions about economic growth rates. The differences are noted in the individual country sections of this publication. Where available, country-specific studies on energy efficiency supplement information from the two regional studies.

5.1 3rd ASEAN Energy Outlook

The 3rd ASEAN Energy Outlook (2011) is the first comprehensive study in which the ASEAN member countries (including the five GMS countries reviewed here) set their energy efficiency savings targets. These targets have become the foundations for proposed energy efficiency policies and programs. The 3rd ASEAN Energy Outlook study reviews energy efficiency trends since 1990 and expected develop...