![]()

![]()

Background

A. Climate Change–A Global Problem

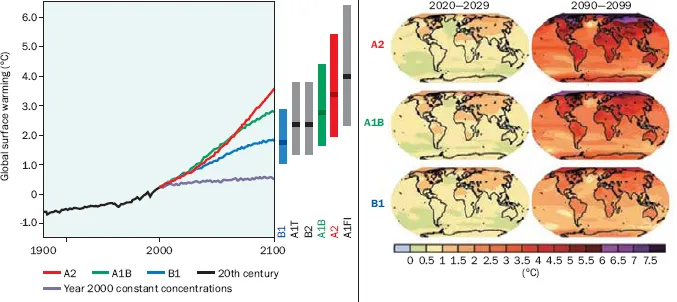

Over the past 150 years, global average surface temperature has increased 0.76°C, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2007). This global warming has caused greater climatic volatility, such as changed precipitation patterns and increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events including typhoons, heavy rainfall and flooding, and droughts; and has led to a rise in mean global sea levels. It is widely believed that climate change is largely a result of anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and, if no action is taken, likely to intensify. Under the most pessimistic emissions scenario developed in IPCC (2000), by the end of this century temperatures could rise to more than 4°C above 1980–1999 levels, ranging from 2.4–6.4°C (Figure 1.1). This would have serious consequences for the world’s growth and development.

Figure 1.1. Atmosphere-Ocean General Circulation Model Projections of Surface Warming

| Note: B1, A1T, B2, A1B, A2, and A1FI represent alternative emissions scenarios developed by IPCC. A1 scenario family describes a world of rapid economic growth and population that peaks in mid-century and declines thereafter. Within the A1 family, there are three scenarios characterizing alternative developments of energy technologies: A1FI (fossil fuel intensive), A1B (balanced), and A1T (predominantly non-fossil fuel). B1 scenario describes a world with rapid changes in economic structures toward a service and information economy, the introduction of clean and resource-efficient technologies, and the same population path as in the A1 family. A2 scenario describes a world with slower per capita economic growth, continuously increasing population, and slower technological change than in other storylines. B2 scenario describes a world with intermediate economic development, continuously increasing global population at a rate lower than A2, and less rapid technological change than in B1 scenario (IPCC 2000). |

| Source: IPCC (2007). |

Climate change is a global problem and requires a global solution. In recent years, addressing climate change has been high on the international policy agenda. There is now a consensus that to prevent global warming from reaching dangerous levels, action is needed to control and mitigate GHG emissions and stabilize their atmospheric concentration within a range of 450–550 parts per million (ppm) (IPCC 2007). The lower bound is widely considered a desirable target and the upper bound a minimum necessary level of mitigation (Stern 2007). The international community is now working toward an international climate regime under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that aims to stabilize GHG atmospheric concentration and provide a long-term solution to the climate change problem through international cooperation based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibility. While the responses of the largest current and future GHG-emitting economies under UNFCCC hold the key, a successful global solution requires the participation of all countries, developed and developing.

While GHG mitigation is essential to preventing global warming from reaching dangerous levels, climate change adaptation is critical to reducing and minimizing the costs, often localized, caused by the unavoidable impacts of GHG emissions already locked into the climate system. Adaptation is particularly important for developing countries and their poverty reduction efforts because the poor–with limited adaptive capacity due to low income and poor access to infrastructure, services, and education–are often most vulnerable to climate change. They generally live in geographically vulnerable areas prone to natural hazards, and are often employed in climate-sensitive sectors, particularly agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, with virtually no chance of switching to alternative sources of income. Thus climate change adaptation, by building adaptive capacity, taking specific adaptation actions in key climate-sensitive sectors, and assisting the poor to cope with climate change impacts, should be a critical part of the development and poverty reduction strategies of every developing country.

B. Climate Change in Southeast Asia

Climate change is likely to be one of the most significant development challenges confronting Southeast Asia in the 21st century. Comprising 11 independent countries1 geographically located along the continental arcs and offshore archipelagos of Asia, the region is widely considered one of the world’s most vulnerable to climate change. Home to 563.1 million people, its population is rising almost 2% annually, compared with the global average of 1.4%. It has long coastlines; high concentration of population and economic activities in coastal areas; heavy reliance on agriculture for providing livelihoods–especially those at or below the poverty lines–and high dependence on natural resources and forestry in many of its countries. As one of the world’s most dynamic regions, rapid economic growth in the past few decades has helped lift millions out of extreme poverty. But the incidence of income and non-income poverty is still high in many countries, and achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) remains a daunting task. Climate change, if not addressed adequately, could seriously hinder the region’s sustainable development and poverty eradication efforts.

Climate change is already affecting the region. IPCC (2007) reports an increasing trend in mean surface air temperature in Southeast Asia during the past several decades, with a 0.1–0.3°C increase per decade recorded between 1951 and 2000. Rainfall has been trending down and sea levels up (at the rate of 1–3 millimeters per year), and the frequency of extreme weather events has increased: heat waves are more frequent (an increase in the number of hot days and warm nights and decrease in the number of cold days and cold nights since 1950); heavy precipitation events rose significantly from 1900 to 2005; and the number of tropical cyclones was higher during 1990– 2003. These climatic changes have led to massive flooding, landslides, and droughts in many parts of the region, causing extensive damage to property, assets, and human life. Climate change is also exacerbating water shortages in many areas, constraining agricultural production and threatening food security, causing forest fires and degradation, damaging coastal and marine resources, and increasing the risk of outbreaks of infectious diseases.

Southeast Asia, like any other developing region, need to take urgent action to adapt to climate change, build resilience, and minimize the costs of the unavoidable impact of GHG emissions already locked into the climate system.

While adaptation is the priority, the region also has an important role to play in contributing to global GHG mitigation efforts. In 2000, Southeast Asia contributed 12% of the world’s GHG emissions, amounting to 5,187 MtCO2-eq, an increase of 27% from 1990, faster than the global average. On a per capita basis, the region’s emissions are considerably higher than the global average, although still relatively low when compared to developed countries. The land use change and forestry sector (LUCF) has been the major source of emissions from the region, contributing 75% of total regional GHG emissions in 2000. The other two key sources are the energy sector (at 15%) and the agriculture sector (at 8%), with emissions from the energy sector growing as much as 83% during 1990-2000, the fastest among the three sources. Southeast Asia needs to explore affordable and cost-effective mitigation measures and to pursue a low-carbon growth strategy.

C. About This Study

Recent years have seen the emergence of many studies aiming at quantifying the economic impacts of climate change and global warming and assessing costs and benefits of adaptation and mitigation options. Among the most influential is The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review (Stern 2007). On the basis of an extensive review of the existing studies (both economic and scientific) on climate change and global warming and modeling exercises using one of the latest integrated assessment models (IAM), the Stern Review concludes that for the world as a whole, an investment of 1% of gross domestic product (GDP) per year is required to avoid the worst effects of climate change. Failure to do so could risk having global GDP up to 20% lower than it otherwise would be. The Stern Review suggests that climate change threatens to be the greatest and widest-ranging market failure ever seen. It warns that people’s actions over the coming few decades could risk disruptions to economic and social activity, later in this century and in the next, on a scale similar to those of the great wars and economic depression of the first half of the 20th century.

The Stern Review provides a global perspective on the economic effects of climate change and global warming. Since its release, there have been various efforts and initiatives to apply the Stern approach to specific regions and countries. As one such study, this review–The Regional Review of the Economics of Climate Change in Southeast Asia–is carried out as a Technical Assistance Project of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and funded by the Government of the United Kingdom. Participated by five of ADB’s developing member countries in Southeast Asia–Indonesia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam–its purpose is to deepen the understanding of the economic and policy implications of climate change and global warming in the region. More specifically, the study aims to:

• contribute to the re...