![]()

02 BOLSTERING THE PUBLIC DOMAIN

In any country, the state bears the primary responsibility for steering the direction of development, and aligning it, through public spending and policies, with a broader vision. This depends in turn on the readiness to enact a coherent policy framework aimed at achieving sustainable development, whether the issues entail jobs, safety nets, education, or pollution control.

Public funds for development come through a variety of channels, domestic and international. Fiscal revenues and external official flows include both traditional sources such as taxes and ODA, and newer ones such as specialized climate funds. The overall mix in the region varies substantially between middle- and low-income countries. Some countries face particular structural constraints and vulnerabilities, such as the Pacific nations, where geography and size place inherent pressures on domestic economies. Specific choice of funding sources and their sequencing may vary based on local circumstances.

Nonetheless, under a “prosustainable development” framework, all sources need to be considered in all contexts, recognizing differences not just in the shares of resources, but in how each category can be best applied. Since development is dynamic, shares and responses can shift over time. Asia’s fiscal prudence has served the region well in sustaining macroeconomic stability and weathering economic crises. The challenge now is to balance this with investments to achieve more inclusive and sustainable growth.

A FOUNDATION IN DOMESTIC RESOURCES

Domestic public resources remain the primary source of financing for development. They are critical to national ownership of public policy and integral to moving toward financial autonomy.1

This remains the case even where international public resources—namely, ODA—play a major role. In countries where levels of ODA are diminishing, it still may retain a vital function in helping to leverage greater domestic resources, both public and private.

Across Asia, taxes, in varying proportions, provide the bulk of fiscal revenues, not falling below 75% in any subregion. Nontax revenues comprise an additional major stream. Some countries benefit as well from sovereign wealth funds. All states face the challenge of protecting the resources they have, including from leakages. Risk reduction strategies are important hedges against the sudden, often large tolls on resources taken by disasters in a hazard-prone region.

Expanding the base: taxation

Tax revenues finance activities essential for development and human welfare. Even where a government uses market borrowing to finance such expenditures, tax revenues ultimately have to service the debt.2 While some level of debt servicing is inevitable, borrowing is only a cash flow instrument—not a substitute for taxation.

All sources need to be considered in all contexts though specific choices and sequencing may vary; since development is dynamic, shares can shift over time

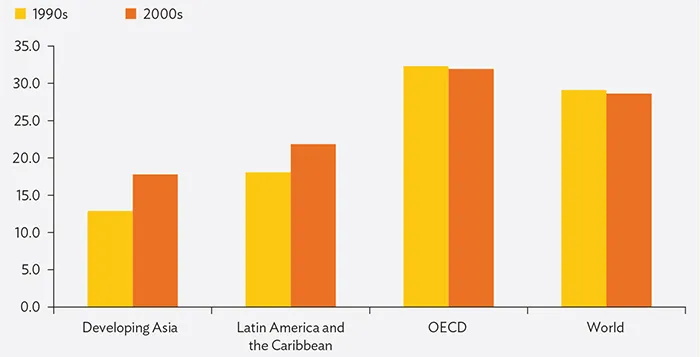

While the positive relationship between taxation and development has been well established, Asia lags behind much of the rest of the world in its ratio of tax revenues to GDP. In the 2000s, this averaged around 17.8% in developing Asia, compared with just below 21.8% in Latin America and 28.6% worldwide (Figure 2.1).3 One estimate found that tapping the full tax potential of 17 Asian and Pacific countries, mostly developing states, would boost tax revenues by around $440 billion a year.4

Figure 2.1: Developing Asia could do more to collect taxes—progressively (Tax revenues as % of GDP)

GDP = gross domestic product, OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Note: Data are weighted averages.

Source: Staff estimates based on data from the International Monetary Fund.

The dominant role of taxation suggests that bolstering tax systems to make them more efficient and effective will be key

The dominant role of taxation suggests that bolstering tax systems to make them more efficient and effective will be one key to improved financing for development. New technological applications, such as the use of ICT in tax administration, can help streamline procedures, reduce leakages, and boost revenues, while institutional reforms can enhance governance and enforcement, and provide incentives for compliance.5

Countries may consider establishing minimum norms for tax-to-GDP ratios that over time help reach global averages. One potential benchmark is government revenues of at least 20% of GDP for those currently below this, and further increases for those already at it. The benchmark may be adjusted for very small economies and countries with structural bottlenecks.

Reasons for the region’s poor record on taxation include the very small percentages of individuals paying income taxes, at both ends of the income spectrum. The many people in the informal sector or agriculture may be too poor to pay direct income taxes, even while they pay indirect ones such as sales taxes. Further, the nature of the informal economy makes it difficult to tax. In the case of wealthier individuals, who could and should be paying taxes, some commonly evade them. Ineffective taxation of capital gains stems in part from concerns about competitiveness, although some countries, including the People’s Republic of China (PRC), have now introduced mechanisms to rectify this tendency.

A shift from taxing trade to taxing goods and services over the past 2 decades has produced significant revenues, yet these have not offset declines in trade tax revenues. Other gaps come from poor collection efficiency, which is below 50% in some countries. Tax exemptions and concessions linked to promoting investment have reduced revenues without consistent compensatory returns, such as more jobs or technology transfer.6

A progressive tax system design can increase equity and minimize negative fallout on economic growth, typically by broadening the base for personal income and value-added taxes (VAT); instituting progressive taxes on property, capital gains, and inheritance; and establishing more corrective taxes and sources of nontax revenues. Equity considerations need to include income parameters and those related to gender, among others. Tax systems can contain explicit and implicit gender biases, for example, when tax exemptions mainly apply to jobs dominated by men.7

Taxes on domestic and international goods and services are the most widespread in Asia, followed by individual and corporate income taxes. While a few countries, such as Indonesia, stand out for depending heavily on income tax,8 the share of income taxes in total tax revenues is lower in developing Asia than in other parts of the world. Broadening the base for and improving collection of personal income tax offers scope for more revenues. Globally, these measures have been instrumental recently in improving tax collection in diverse developing countries, including the least developed states.9

A personal income tax is generally progressive and compares favorably with a corporate income tax in terms of growth effects, albeit unfavorably with VAT and other consumption taxes. By one estimate, a 1 percentage point increase in personal income taxes would reduce income inequality by 0.573 percentage points in Asia, more than the 0.041 percentage points estimated for the rest of the world.10 The difference may reflect a larger percentage of people below the tax-free threshold and high thresholds for top income tax rates.

Use of the VAT is already fairly widespread in Asia. While it imposes relatively low economic costs, it is considered a regressive tax. A better design can make it progressive, however, such as by targeting it to goods and services considered luxuries, and/or applying proceeds to achieving more equitable access to education and health services. Raising the threshold for payment could lower administrative costs from taxing small businesses and reduce regressive tax compliance costs without compromising revenues. Broadening coverage to as many goods as possible would reduce distortions and inefficiencies. Other tax options are corrective or “sin” taxes levied on goods and services deemed to be bad for individuals or society, such as alcohol and cigarettes. These provide a double dividend of revenues and curbs on undesirable behaviors.11

Raising the threshold for taxing small businesses could lower administrative and regressive compliance costs

Taxes levied on immovable property are widely viewed as a fiscal source for local governments. They are likely to be progressive, because the rich tend to have greater property holdings than the poor, and because they track property value. Raising revenue through this source can reduce inequality without undermining growth. It can also offer scope for strengthening local fiscal resources—the PRC, for example, is currently exploring property tax options as part of addressing the high indebtedness of local governments (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1 The People’s Republic of China tu...