- 476 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

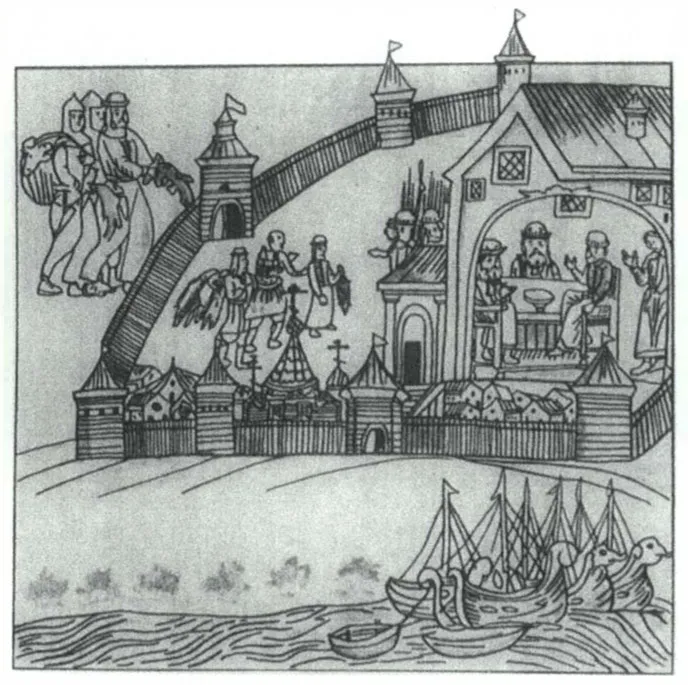

For over five hundred years the Russians wondered what kind of people their Arctic and sub-Arctic subjects were. "They have mouths between their shoulders and eyes in their chests," reported a fifteenth-century tale. "They rove around, live of their own free will, and beat the Russian people," complained a seventeenth-century Cossack. "Their actions are exceedingly rude. They do not take off their hats and do not bow to each other," huffed an eighteenth-century scholar. They are "children of nature" and "guardians of ecological balance," rhapsodized early nineteenth-century and late twentieth-century romantics. Even the Bolsheviks, who categorized the circumpolar foragers as "authentic proletarians," were repeatedly puzzled by the "peoples from the late Neolithic period who, by virtue of their extreme backwardness, cannot keep up either economically or culturally with the furious speed of the emerging socialist society."Whether described as brutes, aliens, or endangered indigenous populations, the so-called small peoples of the north have consistently remained a point of contrast for speculations on Russian identity and a convenient testing ground for policies and images that grew out of these speculations. In Arctic Mirrors, a vividly rendered history of circumpolar peoples in the Russian empire and the Russian mind, Yuri Slezkine offers the first in-depth interpretation of this relationship. No other book in any language links the history of a colonized non-Russian people to the full sweep of Russian intellectual and cultural history. Enhancing his account with vintage prints and photographs, Slezkine reenacts the procession of Russian fur traders, missionaries, tsarist bureaucrats, radical intellectuals, professional ethnographers, and commissars who struggled to reform and conceptualize this most "alien" of their subject populations.Slezkine reconstructs from a vast range of sources the successive official policies and prevailing attitudes toward the northern peoples, interweaving the resonant narratives of Russian and indigenous contemporaries with the extravagant images of popular Russian fiction. As he examines the many ironies and ambivalences involved in successive Russian attempts to overcome northern—and hence their own—otherness, Slezkine explores the wider issues of ethnic identity, cultural change, nationalist rhetoric, and not-so European colonialism.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

SUBJECTS OFTHE TSAR

The Unbaptized

If on some nameless island Captain Schmidt

Sees a new animal and captures it,

And if, a little later, Captain Smith

Brings back a skin, that island is no myth.—John Shade, Pale Fire

The Sovereign’s Profit

The serving and the trading men should be ordered to bring under the sovereign’s exalted hand the non-tribute-paying Yukagir and the Tungus and diverse foreigners of various tongues who live on those and other rivers in new and hostile lands. And the iasak for the sovereign should be taken with kindness and not with cruelty [laskoiu a ne zhestoch'iu], and the people of those lands should be placed, from now on, under the tsar’s exalted hand in direct slavery [v priamom kholopstve] as iasak people for ever and ever.12

He drank it and said: “Fellows, do not have any bad thoughts at all. In all my life, I have never tasted such water anywhere.”Then he drank some water again and put it in front of us.Another old man drank it and said: “No. fellows. it seems that the old man has told us the truth—this water really is delicious.”That old man drank some again and put it in front of us.“Now, young men,” he said. “you taste it.”We tasted it. too, and said:“Yes, our old men have told us the truth.”Then one of the old men said:“I knew it right away and told you not to have any bad thoughts.”Then we all got some more food and water. Our friends started telling us something, but we did not understand anything and pointed to our ears.They showed us something curved and shiny. We took it. looked at it, something was cut out in the middle. They put something in there, then brought some fire. Then they put that thing to our mouths. Then everyone took that thing and started sucking on it. We sat and talked by gestures. They told us:“Next summer come back again. We will bring you various things.”Then we got up and started to leave. Our friends gave us some axes and knives and, in addition to that, gave us all kinds of clothes.15

The arriving Russians built high wooden towers . . . Marveling at that, both children and grown-ups approached the towers and started looking at them carefully. Then they saw that the Russians had scattered sweets, gingerbread cookies, and beads all around the houses. Many children, women, and men came and started picking them up. While they were pick...

Table of contents

- Preface

- Sources and Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Small Peoples of the North

- PART I. SUBJECTS OF THE TSAR

- PART II. SUBJECTS OF CONCERN

- PART III. CONQUERORS OF BACKWARDNESS

- PART IV. LAST AMONG EQUALS