![]()

1

Silicon Prairie

In January 1985, four hundred influential Dallasites gathered by invitation only to celebrate the opening of Infomart, a $97 million experiment in high-technology marketing. Following hors d’oeuvres of seasoned salmon in a brioche shell, caviar-topped potato slices, and mini leek and herb quiches, guests enjoyed a chilled chanterelle terrine with squid and pheasant mousse in a walnut and chives vinaigrette. The second course ushered in cream of artichoke hearts and lobster soup, followed by a palate-cleansing grapefruit sorbet. The veal entrée was followed by a winter salad of watercress, Belgian endive, and tomatoes, flavored with a simple vinaigrette of olive oil and lemon juice, and then a sumptuous dessert: a tulip-shaped cookie shell filled with chestnut mousse and chocolate garnish served alongside a white chocolate leaf and a chestnut-shaped truffle.1

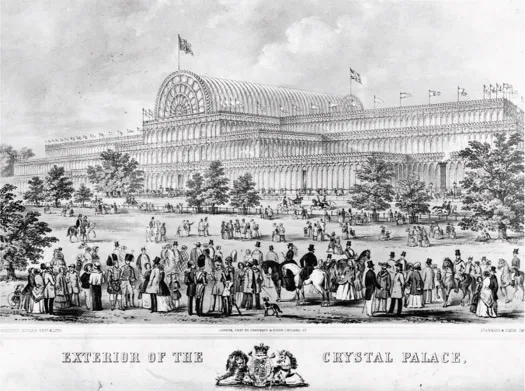

This impressive French feast was just one of sixteen activities heralding Dallas’s new “palace of information,” a 1.6 million-square-foot building patterned after the Crystal Palace designed by Joseph Paxton (who was actually a gardener, not an architect) for the Great Exhibition of London in 1851. Paxton’s one million-square-foot glass and iron Palace was designed to showcase products of the industrial age and further the Exhibition’s goal of giving people “a living picture of the point of development at which all nations will be able to direct their future exertions.”2 Nearly a century and a half later, Dallas’s Infomart was built to showcase the technological innovations of a new information age. Hoping to reflect both the architecture and the “spirit and forward-thinking purpose” of the original Crystal Palace, Infomart architect Martin Growald borrowed many structural details in designing its twentieth-century successor. Like the Crystal Palace, Infomart’s metal and glass frame is decorated with delicate white cast-aluminum panels and built around central semi-circular vaults, both of which contribute to its greenhouse-like appearance. The building’s interior also reflects elements of its predecessor, including an elaborate crystal fountain, English-red phone booths, and a central atrium (sans the original aviary). Even its wood floors bear a pattern identical to that of the original Crystal Palace.3

All that nineteenth-century charm, however, was really just a vessel for late twentieth-century technology. Infomart was designed as a trade mart for computers, a “high-tech bazaar” with seven floors of showrooms, exhibition space, lecture halls, and meeting rooms, all equipped with cutting-edge computing and telecommunications equipment.4 This revolutionary application of the trade mart concept (concentrating multiple vendors in a single commercial location) to high-tech products and services was expected to draw over 350,000 visitors a year and to cement Dallas’s position as a high-tech center worthy of national acclaim. In honor of Infomart’s opening, Governor Mark White declared the week beginning January 21, 1985, Information Processing Week in Texas.5

From its inception, Infomart had its critics. Some took an aesthetic stand against the structure, describing its lacy white exterior as a “metal-and-glass wedding cake” and “a giant 1850s Mississippi side-wheeler about to bust loose from its moorings.”6 Others were more concerned about its fiscal viability; despite the pomp that accompanied its opening, Infomart opened with less than half of its available exhibition space filled. (It also turned out that many of its frequent visitors came not to shop for computers but to ride in the glass-walled elevators.) Over the next two decades, Infomart’s prospects, and public perception thereof, waxed and waned. Although the space never achieved its intended goal—the computer mart concept was scrapped after only a few years—the story of how (and how much of) Infomart’s space was in use at a given time intertwines with the broader history of Dallas’s high-tech industries and the region’s efforts to establish itself as a high-tech region on par with California’s famed Silicon Valley. That story, however, begins much earlier, in a time when Infomart was not even a glimmer of glass and metal in Dallas’s collective eye.

Figure 1. The Crystal Palace. The original palace, built for the 1851 Great Exhibition of London, burned to the ground in 1936. Infomart has since been recognized by Great Britain’s Parliament as its official successor. Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Until World War II, Dallas was a minor manufacturing center in the United States, specializing in food processing, apparel manufacturing, and printing and publishing. During World War II, Dallas and its neighboring city Fort Worth benefited from the booming wartime defense industry, which, due to some serious lobbying on the parts of Texas legislators Sam Rayburn and Lyndon Johnson (then Senate majority leader), brought numerous defense plants to the area. Companies were also drawn to Dallas’s pro-business environment, with its low taxes, inexpensive land, cheap and largely un-unionized labor force, affordable cost of living, and abundant natural resources. Manufacturing was already the primary source of employment in Dallas County by the 1940s, but the number of manufacturers in the county more than tripled between 1947 and 1987. In 1949 alone, five new businesses opened each day, and thirteen new manufacturing plants opened every month. Many of those new ventures were concentrated in the computing and electronics industries. Companies such as Texas Instruments, originally an oil and gas exploration company, won sizable defense industry contracts and drew top engineering talent to the region. Such companies also spawned generations of spin-off companies, helping to grow Dallas into the nation’s third-largest technology center by 1970.7 The 1974 opening of the Dallas–Fort Worth International Airport, positioned roughly equidistant from New York, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and Toronto, strengthened the city’s reputation as a national financial and business center and its attractiveness as a home for corporate headquarters.

Figure 2. Infomart, modeled after the original Crystal Palace, stands just off a major freeway in downtown Dallas. Photograph by Nancy Windrow-Pearce.

Following the tendency of high-tech firms to develop in clusters (as evidenced by California’s Silicon Valley, Boston’s Route 128, and North Carolina’s Research Triangle) the companies that sprung from or came to do business with Texas Instruments and other Dallas tech firms stuck close by their larger peers, many of whose headquarters were located in Richardson, a suburb north of Dallas.8 Land was inexpensive and plentiful in Richardson, which soon became known as “The Electronics City,” and the region proved a magnet for new ventures and corporate relocations. Although the area’s high-tech roots lay in the manufacturing of computers and other upscale electronics, this clustering of companies, capital, and talent left Dallas well positioned to expand quickly into other high-tech fields as they emerged.

With the breakup of AT&T and the subsequent deregulation of the telecommunications industry in the early 1980s, Richardson found itself home to hundreds of start-up telecom companies looking to enter this new market (which opened further when the Telecommunications Act of 1996 allowed any communications business to compete in any market against any other). Most of these companies were pioneered by former employees of computing and communications companies already in the area and amply funded by venture capital. These firms organized themselves along a stretch of highway running from Dallas through Richardson and up into Plano, Richardson’s neighbor to the north, later expanding to both the east and the west along perpendicular President George Bush Turnpike, forming a T shape. This region quickly earned the title “Telecom Corridor,” and its rapid growth and speedy cornering of the telecom market soon garnered national attention. By 1989, the Wall Street Journal was calling Richardson one of the “Boom Towns of the 1990s.” In 1992 the Telecom Corridor appeared on the cover of Business Week as one of “America’s New Growth Regions,” and that same year Richardson’s Chamber of Commerce registered the moniker “Telecom Corridor” as its official trademark.9 Still, Dallas leaders believed that their region was being overshadowed by other, more famous tech centers like Silicon Valley and Boston and yearned to establish Dallas as their equal, if not their better.

Although the Bureau of Labor Statistics had already named Dallas a leading center of high-tech employment the year before, in 1984 Dallas Mayor Starke Taylor created a twenty-six-member task force to evaluate the state of the city’s high-tech situation.10 Taylor’s concern was well timed, as both the computing and semiconductor industries fell into a slump in 1985, leading to widespread layoffs and the closing of many smaller companies.11 It was in this environment that Infomart opened its doors, and many attributed the building’s failure to reach its projected occupancy of 100 percent by 1986 to the continuing shakeout from this downturn. Others blamed Infomart’s shuffling start to flaws in the assumption that computers could be bought and sold in the same manner as clothing and furniture.12 (Infomart was built within a larger complex known as Market Center, which already housed four large, architecturally nondescript buildings used as wholesale markets for, among other things, furniture and apparel.) In an attempt to woo a different market segment, Infomart executives ditched the one-stop-shopping model and refocused on providing services to companies and their customers, namely education on computer systems and software applications. This shift mirrored a larger one taking place in the high-tech industry. The United States, it was argued, was moving from an industrial economy based on manufacturing to a postindustrial “service/information economy.”13 In response, companies began to focus less on manufacturing and selling computer hardware and more on marketing and providing information technology (IT) services designed to solve business problems with customized technology. In telecommunications, the new craze was fiber-optic technology, which would vastly increase the capacity of the U.S. long-distance telephone system and allow users to transmit both voice and data faster and with less distortion than current microwave systems. Well placed to meet this new demand, Infomart’s occupancy rose to just over 60 percent in 1988, fueled in great part by companies’ need for access to the advanced fiber-optic network that ran beneath the building’s patterned wood floors.

The new IT and telecommunications companies needed people in addition to bandwidth. High-tech employment grew more than twice as fast in Texas than in the nation as a whole from 1988 to 1994, and computer-related services surpassed manufacturing as the state’s largest high-tech industry. The Dallas–Fort Worth area was home to much of that growth, accounting for over half of the state’s high-tech jobs (and almost 80 percent of Texas’s telecom jobs) in 1995.14 The local supply of tech workers, extensive as it was, proved inadequate to meet the growing demand for skilled tech workers, and by the year 2000 Dallas was importing engineers and computer scientists from other countries to fill their payrolls.15

The spectacular rise of the Internet and the dot-com companies it birthed over the course of the 1990s has been chronicled extensively elsewhere.16 Essentially, once the Internet morphed from a government-funded collection of networks that was free to the public into a privatized commercial enterprise, venture capital firms, many located in northern California, began pouring money into companies looking to make a profit selling, facilitating, or augmenting people’s access to and use of the Internet. The apparently infinite supply of venture capital for high-tech start-ups and the phenomenal success of early dot-com IPOs (initial public offering, or a company’s first sale of stock to the public) led many in the late 1990s to announce the birth of a “New Economy.” Characterized by “a fundamentally altered industrial and occupational order, a dramatic trend toward globalization, and unprecedented levels of entrepreneurial dynamism and competition—all of which have been spurred to one degree or another by revolutionary advances in information technologies,” this New Economy was one in which the old rules of economics were said to no longer apply.17 A company could therefore be labeled successful even with no profits or identifiable source of future profits.

With old economic models for evaluating a company’s current and potential future worth (such as the ratio of price to earnings) deemed obsolete, stock valuations became increasingly speculative (and, it has since been revealed, increasingly fraudulent). A nation of investors looking to boost their portfolios with hot Internet stocks often based their decisions on whether and what to buy or sell on media coverage that tended toward uncritical hype of both individual dot-com companies and the tenets of the New Economy.18 Eager to take advantage of this speculative bubble, venture capitalists and executives rushed seedling start-ups to IPO while the market was bullish on all things Internet. Although Silicon Valley’s existing technology infrastructure, ready pool of tech talent, extensive funding sources, and liberal, risk-inclined culture combined to make the region the United States’ dot-com center, other regions—Dallas included—offered their own sizeable contributions to the growing Internet industry.

In January 1998, D Magazine (the D stands for Dallas) challenged Dallas entrepreneurs and investors to dive into the admittedly risky but potentially superlucrative world of dot-com start-ups.19 The article alleged that Dallas, usually a hotbed of technological innovation and entrepreneurship, was revealing itself to be a laggard in the high-tech explosion because engineers and other tech workers were too comfortable in their secure, well-paid telecom jobs to take a risk on entrepreneurial v...